Teaching Voting Rights in the Time of Coronavirus

What Our Students Should Know About the Struggle for the Ballot — but Won’t Learn from Their Textbooks

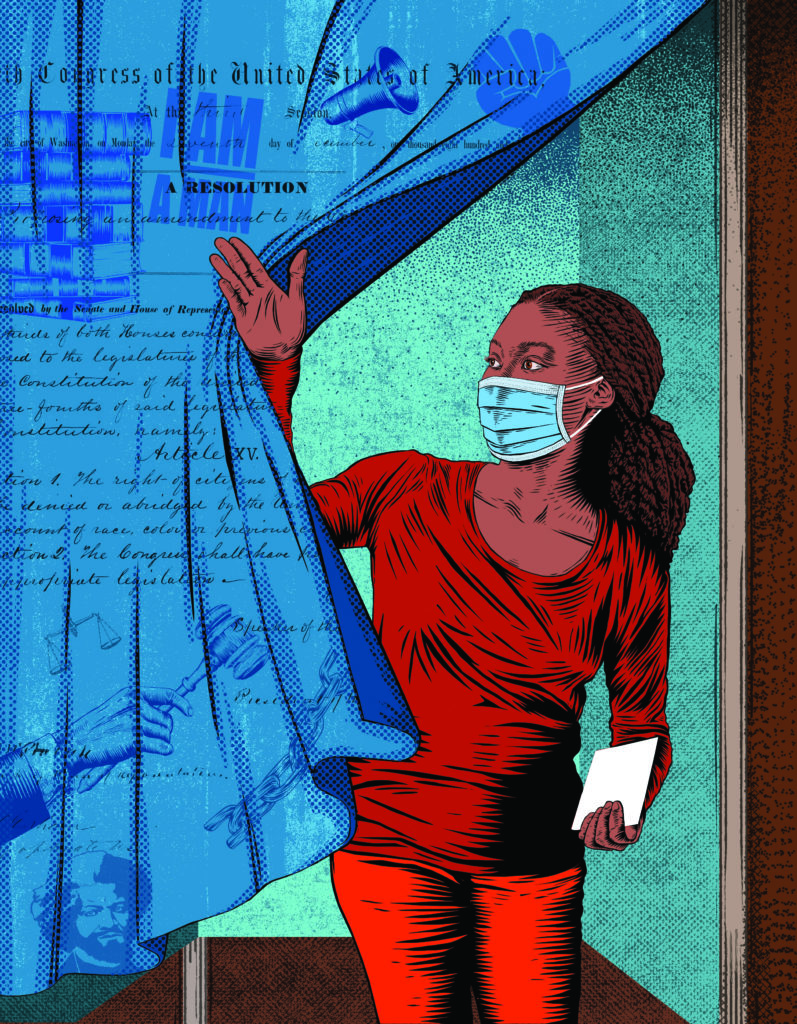

Illustrator: Boris Séméniako

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the ratification of the 15th Amendment, which promised “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Given the dizzying array of disruptions to our lives in this moment of pandemic, one could be forgiven for failing to register this anniversary. But the fight for voting rights enshrined in the 15th Amendment is still very much alive, and more critical now than ever — and needs to be taught to every student in this country.

The coronavirus pandemic makes in-person voting dangerous, literally a potential death sentence. Indeed, when Wisconsin failed to postpone in-person voting in early April, infected people voted and likely infected others. And the people most vulnerable to coronavirus are also the most likely to already face disproportionate obstacles to voting: Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities, the elderly, the poor, the incarcerated. Voting rights activists are calling for immediate implementation of measures that are basic, long overdue, and which will protect the health of all voters: extension of early voting, online registration options, universal mail-in-ballots. But Republican legislatures across the country balk, citing logistical barriers and the dangers of “voter fraud.” Voter fraud, as all recent reputable studies agree, is very, very rare in the United States. A 2014 investigation published in the Washington Post found only 31 instances (out more than 1 billion ballots) of voter impersonation fraud. Recently, however, President Trump has dispensed with even the pretense of the fraud argument and made clear the Republican Party’s real concerns. As he told Fox News, implementation of vote-by-mail and other pro-democratic measures would create “levels of voting that if you’d ever agreed to it, you’d never have a Republican elected in this country again.”

From voter ID laws to voter roll purges, gerrymandering to poll closures, on the 150th anniversary of the 15th Amendment, the right to vote is under attack and the stakes are high.

From voter ID laws to voter roll purges, gerrymandering to poll closures, on the 150th anniversary of the 15th Amendment, the right to vote is under attack and the stakes are high. It is critical that students learn about the fight for voting rights, past and present. Textbooks will be of little use. Though the book adopted by my school district outside of Portland, Oregon, to teach 10th- and 11th-grade U.S. history, National Geographic’s America Through the Lens (2019), mentions the 15th Amendment, adopted in 1870, the 19th Amendment, adopted in 1920, and the Voting Rights Act (VRA), passed 45 years later, the story ends there. The text offers the false impression that the history of voting rights in the United States is a hopeful tale of steady progress, culminating in 1965. It provides them no context to understand our current moment.

A good place to begin a study of today’s voting rights struggles is Reconstruction, a time when, as Adam Sanchez notes in an article in the Nation, “Black lives mattered.” Using a role play written by Rethinking Schools curriculum editor Bill Bigelow, students in my classroom imagine themselves newly freed in the months immediately following emancipation and wrestle with the key questions of freedpeople — how to access land, political power, safety, and education. There is disagreement among my 21st-century students — as there was among the real 19th-century freedpeople — about what should happen to Confederate leaders (execution? amnesty?) and about whether to grow cotton to appease Northern elites or permanently renounce a crop that one cannot eat and that is so closely connected with slavery. But about voting, students rarely disagree. Trying to imagine themselves as freedpeople, they see the vote as critical to all their other aspirations. In follow-up discussion of this activity, we reflect on what really happened during the Reconstruction Era. Students are outraged to learn that plantations were returned to Confederates rather than allocated to freedpeople. But they celebrate the 15th Amendment, which immediately extended the vote to nearly 500,000, mostly formerly enslaved, Black men across the South. Like freedpeople themselves, my students see the right to vote as fundamental to freedom.

Fundamental, but not secure. In the years following the passage of the 15th Amendment, myriad forms of racism — violence, devious new voting qualifications, economic exploitation, denial of education — combined to undermine the 15th Amendment and disenfranchise millions of Black people. By the middle of the 20th century, less than 7 percent of eligible African Americans in Mississippi were registered to vote. Though white supremacists succeeded in their campaign of disenfranchisement, Black people and their allies never stopped demanding the franchise, through legal action, civil disobedience, and mass politics.

Though my textbook makes little connection between Reconstruction and the Civil Rights Movement — indeed they are separated by hundreds of pages in its relentlessly chronological march through history — it was the unceasing activism of Black people, and others, that led to the passage of the VRA and finally secured the promises of the 15th Amendment for millions of voters. In the voting rights mixer lesson I wrote for the Zinn Education Project, students appreciate this full-circle moment. Through role play, students encounter dozens of stories, across centuries, about the fight for voting rights. They learn about the achievements of the Reconstruction Era when they “meet” figures like Frances Harper, Frederick Douglass, and William T. Combash — and how Reconstruction promises were restored, renewed, and reinvigorated by later activists like Fannie Lou Hamer, Lawrence Aaron Nixon, and Lamar Smith. From Elzie McGill, an activist from Lowndes County, Alabama, students learn that by outlawing many of the voting qualifications used to deny Black people their 15th Amendment rights, as well as requiring strong federal oversight of state and local elections, the VRA was one of the most effective pieces of legislation in U.S. history. It resulted in the immediate registration of hundreds of thousands of new Black voters.

In a typical U.S. history textbook, the struggle for voting rights ends in 1965. Textbooks describe the VRA — rightly — as a major victory for democracy and the Civil Rights Movement. My students’ textbook, America Through the Lens, was published in 2019, and even covers the 2016 election, but it does not mention the fight for voting rights — or the rise of new forms of voter suppression — since 1965. A number of other textbooks I consulted end their coverage of voting rights at the VRA too, with a couple mentioning the passage of the 26th Amendment in 1971.

Though our students’ textbooks suggest otherwise, the fight to vote is very much alive, which is why the lesson I described above also includes more than a dozen examples of recent voter suppression and activism, presented alongside those of earlier eras. When students encounter side-by-side stories of 19th-century property requirements, 20th-century poll taxes, and 21st-century voter ID requirements, the lesson is clear: Antidemocratic measures that keep the vote out of the hands of the poor are not bygones of a less enlightened era, but recurring motifs in the U.S. story. Why, students wonder, is voting suppression back in vogue?

Over the last decade, the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), the right-wing group that develops “model” legislation, has sought to transform U.S. politics at the state level, including through voter suppression. ALEC crafts cookie-cutter versions of proposed laws that are brought to states to realize a conservative utopia of deregulation, tax breaks, and massive disinvestment from public spending. In 2011, ALEC made voting qualifications one of its priorities, and 33 states introduced so-called “voter ID laws” in that year alone. These laws require burdensome forms of identification to vote — forms of identification that are less common among poor and nonwhite voters. The calculus is as obvious as it is abhorrent. Poor, Black, and Brown voters are the least likely to support ALEC’s legislative agenda and the most likely to be blocked from voting by these new laws.

As students participating in the voting rights mixer learn from people like Aracely Calderon and Maggie Coleman, ALEC’s agenda of disenfranchisement got a boost from the Supreme Court in 2013 in Shelby County v. Holder, when it ruled that a critical piece of the Voting Rights Act was unconstitutional. Since 1965, the VRA required that locales with an established history of voter suppression or discrimination get permission — “preclearance” — from the federal government before changing voting rules or registration qualifications. State and local governments had to prove to regulators that the new policies had no discriminatory intent toward nor disparate impact upon historically disenfranchised groups — before making any changes. By doing away with preclearance, Shelby gave states the power to pass new legislation related to voting with no oversight.

The lethal combination of conservative activists like ALEC and the hands-off approach signaled by the Supreme Court means voter suppression is on the rise. According to the Brennan Center, 25 states have enacted new voting restrictions since 2010.

Seemingly each day brings a new example. Georgia purged voter rolls. North Dakota refused to allow Native Americans to use their tribal identification to vote. In spite of the overwhelming decision of Floridians to reinstate voting rights of convicted felons, the Republican-controlled Legislature enacted a modern-day poll tax to block them. Although my textbook mentions Russian interference in the 2016 election, it is completely silent on this other kind of “interference” in the democratic process.

The assault on voting rights is fierce, but so is the resistance.

The assault on voting rights is fierce, but so is the resistance. Organizations like the ACLU and the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund have been active on the legal front, challenging each new law, appealing each bad ruling. At the heart of these cases are would-be, should-be voters who will not go quietly. Voters like Ms. Rosanell Eaton, a 94-year-old Black North Carolinian, who made 10 trips to the Division of Motor Vehicles and drove more than 200 miles to get a required form of voter identification because the name on her driver’s license did not exactly match her voter registration. Or voters like Gladys Harris, whom students meet in the mixer, a 66-year-old Black woman with disabilities from Wisconsin whose three forms of identification did not satisfy the state’s strict voter ID requirements.

Activists are, as always, critical to the organizing against voter suppression. In North Dakota, the Lakota People’s Law Project raises funds for and organizes volunteers to distribute free identification with street addresses to thousands of Native Americans who would otherwise be turned away at the polls for lack of a proper ID. All over the country, activists use their own cars, often taking unpaid time off of work, to ferry elderly relatives or community members to faraway polling stations or to obtain the new forms of identification required for voting. My textbook details the dueling platforms of the two main-party candidates in the 2016 presidential election, but says nothing about their positions on voter ID laws or the Shelby case.

As I write this article in April 2020, I am sitting in my 2nd-floor office (read: bedroom), with the murmurs of my husband videoconferencing with his middle school science students in the next room, and the tinny sound of my child’s Zoom violin lesson on the floor below. It is hard to recall that there was a time before the coronavirus shutdown of schools, a time when the curriculum calendar showed April as the month in which my U.S. history students would — in our brick- and-mortar classroom — read Fannie Lou Hamer, watch Eyes on the Prize, and learn about the fight for voting rights, past and present.

But here we are. And though I am uncertain exactly how I will carry forward my voting rights curriculum during this period of school closure and emergency online education, it is urgent that I do so.

The 15th Amendment was ratified in 1870 thanks to 19th-century anti-racist visionaries and activists. The Voting Rights Act was enacted in 1965 thanks to 20th-century visionaries and activists. It will be left to 21st-century visionaries and activists to demand a renewal of our government’s commitment to voting rights. For educators, we need to nurture those visionaries and activists in our classrooms, whether online or in person. One way to start is to push back against textbooks’ erasure of the modern fight for the vote at the same time we teach lessons that bring those struggles to life.

The Zinn Education Project has partnered with Color of Change on a campaign (zinnedproject.org/15th-amendment) to mark the 150th anniversary of the 15th Amendment. The campaign offers “Who Gets to Vote? Teaching About the Struggle for Voting Rights in the United States” (bit.ly/ZEP_CoC_Voting), a classroom unit with three lessons, and “A Toolkit for Voting Rights Advocates” by Color of Change (bit.ly/ZEP_CoC_Voting2).

Subscribe to Rethinking Schools magazine at bit.ly/SubscribeToRethinkingSchools.