Teaching the Truth About National Parks

National parks are the best idea we ever had. Absolutely American, absolutely democratic, they reflect us at our best rather than our worst.

—Wallace Stegner

Advocates for Yellowstone may have thought they were preserving a wilderness area. But it is more accurate to say that they were inventing it. . . . Preservation of the country’s national parks and Indian removal proceeded in lockstep motion.

—Ted Steinberg

When Yellowstone was established, the Plains Wars were raging all around the park’s borders. It was as though the government paused mid-murder to plant a tree in the victims’ backyard. . . . Viewed from the perspective of history, Yellowstone is a crime scene.

—David Treuer

National parks were a central focus of my family’s vacations when I was growing up. In an old camper that my dad restored, my sister and I peered out the window in awe as we drove through dramatic landscapes on highways like Going-to-the-Sun Road in Glacier National Park or the Trail Ridge Road in Rocky Mountain National Park. As we got older, my family began to venture off the main roads and away from crowds, hiking into more remote areas in Mt. Rainier National Park — through old-growth forests, next to the headwaters of rivers, across glaciers and over mountain passes — with wilderness permits dangling from our backpacks. All these experiences played an important role in shaping my early understanding that these seemingly “untouched” landscapes represented nature in its truest form. As a park visitor, I was often reminded of the importance of preserving and protecting our “nation’s natural heritage.” Visitor centers, roadside signs, and talks by park rangers all helped to reinforce the legacy of the park service and early conservationists like John Muir and Teddy Roosevelt, who I was told had worked to preserve these places for the future enjoyment and recreation of families like mine. Rarely, if ever, was I asked to confront another legacy of our national park system: the removal, dispossession, and genocide of Native Americans that created the “wilderness” areas where I had these experiences.

I’ve been teaching about the history of national parks in my Environmental Justice class for several years. It’s a story that deserves a more prominent place in the U.S. history curriculum as it reveals fundamental aspects of the relationship between conquest, Indigenous peoples, and nature. Too often, teachers address these themes through topics like “manifest destiny” and “westward expansion” that can normalize the massive land theft upon which the United States was built. By contrast, a critical look at the national parks presents an opportunity for students to consider how and why the first parks were created as part of the U.S. government’s wars with Native Americans, as the opening quotes above suggest. Discussing the national parks in our classrooms can also raise important questions about the natural world and our relationship to it, as well as contemporary issues of environmental justice, like the role the parks could play in restoring a small, but meaningful, portion of the land stolen from Native peoples.

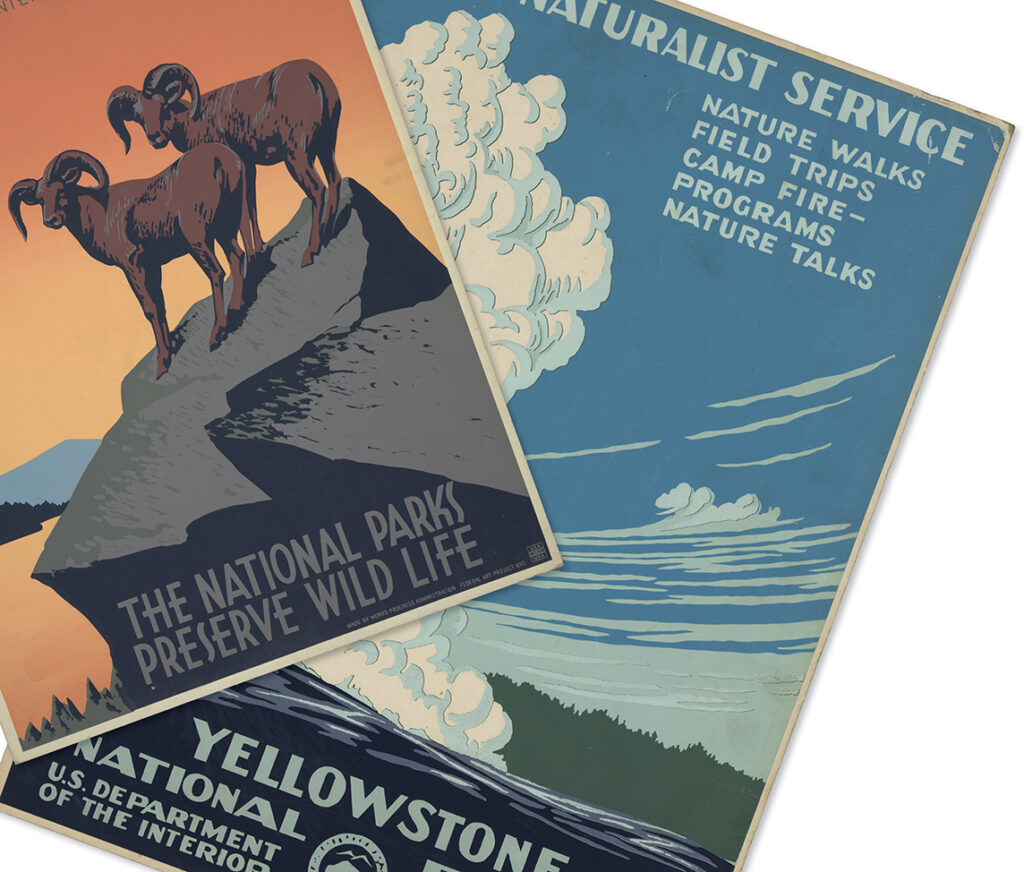

Standard U.S. history curricula credit Progressive Era figures like Teddy Roosevelt with birthing an ethos of environmental conservation that balanced principles of “preservation” and “efficient use,” as public lands were either protected as recreational wilderness areas or designated for resource extraction. Here’s an example from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s high school textbook American History: “Conservationists like Roosevelt . . . did not [always] share the views of [John] Muir, who advocated complete preservation of the wilderness. Instead, conservation to them meant that some wilderness areas would be preserved while others would be developed for the common good.” This equivocation is typical of the history curriculum produced by big textbook corporations; with “some wilderness areas preserved” and “others developed for the common good,” readers can assume that everyone wins. But as is true with so much of the environmental thinking inherited from the conservationists of the Progressive Era, this is a narrative that needs complicating in our classrooms. Looking at history through an environmental justice lens demands that we look closer at the legacies of conservationists like Roosevelt whose support for national parks was informed by racist views that American land “should pass out of the hands of its . . . aboriginal owners and become the heritage of the dominant world races.”

Early attempts to “protect” nature are rooted in the exclusion of humans.

Given that John Muir and Teddy Roosevelt are generally held in high regard for their contributions to the conservation of our national parks, I want students to see that the racist views they both espoused were not merely distasteful, but played a significant role in shaping ideas and institutions within U.S. environmentalism. I want students to see that the conservation model at the heart of the 20th-century environmental movement in the United States grew out of the genocidal war against Native Americans — in fact, after expelling Indigenous tribes from the areas of Yellowstone and Yosemite, both parks spent decades under military occupation before being handed over to the park service. I also want students to see that these early attempts to “protect” nature are rooted in the exclusion of humans, an idea eventually ratified in the Wilderness Act of 1964, which describes wilderness as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

By creating parks that preserved nature from active use by Indigenous inhabitants (or anyone else), while “saving” parks for purely recreational purposes, the “pioneers” of conservation helped define an American relationship with nature that presumes humans are capable only of exploiting the natural world, not coexisting within it. Finally, I want students to see that these “forefathers” of 20th-century environmentalism helped to build a movement so focused on the preservation of wild places, that it would fail to recognize the fundamental connections between social and environmental justice for decades to come.

To start our lesson on “telling the truth about national parks,” I’ve shown a five-minute video from Grist called “Our national parks belong to everyone. So why are they so white?” The video shares historical examples and recent statistics about the racial demographics of park visitors, so I encourage students to take notes on what they find most interesting and/or surprising. It opens with a quote from John Muir, who said about national parks that “Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wildness is a necessity.” The narrator explains that although this quote might hold true for families like mine growing up — white and middle class — that the histories of Indian removal and racial segregation within national parks have made them decidedly less welcoming places for communities of color. Delving further into this history, the video introduces students to the influential conservationist Madison Grant, a contemporary of Teddy Roosevelt and John Muir, who not only helped inspire the creation of multiple national parks but was also a widely known eugenicist and advocate for “scientific racism.” Grant wrote a book called The Passing of the Great Race, praised not only by President Teddy Roosevelt but also by Adolf Hitler, who referred to it as “his bible.” Roosevelt and Grant collaborated to pass early conservation laws, and were members of the country’s first conservation organization, the Boone and Crockett Club. But Grant’s name never shows up in standard high school textbook entries about Roosevelt’s conservation legacy. So I appreciate that the Grist video leads with a clear-eyed view of the fundamentally racist beginnings of U.S. environmentalism. In students’ responses to the video, many emphasized the fact that one of the founders of the national parks movement was a eugenicist, while several others focused on a quote that “every square inch of land in the national park system” was stolen from Indigenous people.

It’s helpful for students to evaluate conventional versions of history alongside more critical portrayals like the Grist video, so the next source we turn to in our study of national parks is the award-winning Ken Burns documentary National Parks: America’s Best Idea, which first aired on PBS in 2009. The original episodes are too long to show in class, but I’ve used a shorter clip from the PBS website called The Creation of Yosemite National Park, which tells the story of Muir and Roosevelt’s famous 1903 camping trip that eventually led to protection of the national park as it stands today. I ask students to take notes on how Muir, Roosevelt, and the land of Yosemite are described; I also ask them to think about what might be missing from the documentary.

One student pointed out that Burns’ documentary describes Muir as a “famous, kindhearted conservationist who was well loved.” Another noticed that the video portrays Roosevelt as “irresistibly charming,” “honorable,” and “devoted to the protection of nature for future generations.” Regarding the land, one student wrote that Yosemite is described as “untouched by humans,” and a “temple built by no hand of man.” Thanks to the Grist video’s history lesson we had just watched, most students quickly noticed that the PBS clip misses any mention of the Indigenous people who had lived in and around Yosemite for generations. To be fair, Burns’ original longer national park episodes make sporadic attempts to document settler and government violence against Native people, but in a way that suggests the violence was a regrettable remnant of earlier Indian wars, not something integral to the process of creating the parks that we’re told are “America’s Best Idea.”

To follow the Ken Burns clip, I assigned a short excerpt from Mark Dowie’s excellent book,Conservation Refugees: The Hundred-Year Conflict Between Global Conservation and Native Peoples. The first chapter looks at how the creation of Yosemite National Park became a model for “exclusionary conservation,” a process replicated thousands of times around the world, expelling millions of Indigenous inhabitants from traditional homelands in newly created national parks and other “protected” areas. The global implications of “America’s best idea” could make its own important unit of study, but for this lesson, I was most interested in having students read Dowie’s portrait of Muir, Roosevelt, and the deliberately exclusionary process that created Yosemite. The contrast with the Ken Burns documentary is shocking: Muir describes the Ahwahneechee band of Miwok people living in Yosemite as “ugly, some of them altogether hideous,” and argues that a place as grand as Yosemite, “where nature has gathered her choicest treasures,” was no place for “such debased fellow beings.”

In response to this contrasting portrayal, one student wrote: “This was very clearly left out of the Ken Burns documentary. John Muir was painted as a man who appreciated and worshipped nature when, in reality, he was only a worshiper of the land once the Indigenous people had been displaced.” Muir’s overt racism is not the only juxtaposition that students take away from the excerpt; Dowie also examines the historical fiction maintained by Muir and repeated in the PBS documentary, that Yosemite was an “untouched wilderness”:

In his writings Muir insisted that Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove had, before the arrival of Euro-American settlers, been unoccupied virgin wilderness. He claimed that any Indians on these lands were temporary nomads passing through. Nothing could be further from the truth. . . . What Muir saw the first time he viewed that bucolic valley might have seemed like wilderness landscape, but it wasn’t. It was a tended wilderness, a cultural landscape. In fact, for 4,000 years the valley had been a productive, rotational garden cared for by hundreds of full-time gardeners that sustained generation upon generation of Miwok, Yokut, Paiute, and Ahwahneechees.

This analysis offers one of the most important lessons I’ve taken away from teaching this topic, and one I was grateful to see reflected in at least one student’s response: “By erasing Indigenous history and removing [Indians] from their land, Muir and others painted themselves as heroes fighting for nature. But Muir’s idea of the pristine, untouched nature of Yosemite was false, and wouldn’t have existed if not for the people he fought so hard to kick out.” The lesson here is not only historical, but also has implications for Indigenous demands of reparations for centuries of land theft, embodied by a growing “landback” movement that calls for, among other things, returning land to Indigenous stewardship. By disregarding the long-standing and influential relationships Indigenous peoples had with lands being “preserved” as national parks, their establishment led not only to the loss of Native homelands, but helped create ideas about wilderness that perpetuate the continued denial of Indigenous dispossession to this day.

“We created this idea that we don’t belong in nature or that we are superior to it.”

I’ve used an additional excerpt with students from Ted Steinberg’s book Down to Earth: Nature’s Role in American History, about the creation of Yellowstone National Park. Although Congress preserved Yosemite in 1864 as federally protected land, Yellowstone has the distinction of being declared in 1872 the first U.S. national park — and likely the first in the world. Throughout Down to Earth, Steinberg uncovers stories of how the natural world is implicated in commonly taught eras and themes from U.S. history, and makes a strong argument that environmental justice belongs in all U.S. history classrooms. Steinberg argues that Yellowstone, as a manufactured “wilderness,” was designed not only to meet the desires of adventure-seeking, wealthy tourists and the railroad industry that delivered them there, but ultimately to celebrate the nation’s “natural heritage” and to ratify the success of “manifest destiny” and wars of extermination against Indigenous Americans. Steinberg writes:

Here was a picture-perfect spot to knit together the fledgling nation, a place so majestic and so capable of uniting the country under God that Congress purchased a painting of it . . . to hang in the Capitol. To congressmen such as Henry Dawes of Massachusetts, who worked to establish the park, Yellowstone, as the site was named, represented nature in its most pristine state, a beautiful but harsh wilderness environment so formidable that not even Indians, he asserted, could live there, a place seemingly without history.

Of course, several tribes lived in or near the park for generations and used it for hunting, fishing, and gathering, including the Shoshone, Crow, Blackfeet, and Bannock. As was the case with Yosemite, it took the willful erasure of the tribes’ claims to “preserved” lands for advocates like Henry Dawes to declare Yellowstone a pristine wilderness devoid of human history. As one student wrote: “This wasn’t solely about the conservation of natural lands, but also about the pioneering and taking of the West as well. It’s nice that there was appreciation of the beauty of the land, but it came as part of the expansion of U.S. power.” Another student, reflecting on Steinberg’s quote that advocates for Yellowstone “invented” a wilderness, shared their concern that “we created this idea that we don’t belong in nature or that we are superior to it by manufacturing an environment for our entertainment.”

I recognize that “teaching the truth” about U.S. conservation and the problematic history of national parks could add to a sense of fatalism common with students today — that all environmental conservation efforts are either too insignificant or doomed to repeat mistakes of the past, so why bother? Furthermore, it’s possible to mistake this critical analysis for a disregard of the tireless battles to protect locally and federally preserved areas across the United States from the unrestrained development that defines so much of our current landscape.

It’s undeniable that in an era of climate chaos, mass species extinction, and unrelenting capitalist exploitation of the natural world, we need stronger environmental protections. At the same time, if we don’t examine the roots of the conservation movement that so often espoused the racial superiority of its founders as a motive for protecting natural resources, today’s environmental movement may continue to practice the same kind of “exclusionary conservation” core to the creation of national parks like Yosemite and Yellowstone.

In fact, some conservation measures suggested as “solutions” to the climate crisis in recent years — notably the U.N. forest protection program known as “REDD” — have been decried by Indigenous groups as neo-colonial land grabs that not only threaten Native sovereignty, but also undermine the ability of Indigenous peoples to protect the very lands they have stewarded for generations.

This is one reason that for the last couple years I’ve concluded our study of the national parks by listening to a conversation with Ojibwe writer David Treuer, from the Atlantic podcast The Experiment, called “The Problem with America’s National Parks.” Treuer is author of the Atlantic cover story “Return the National Parks to the Tribes,” which prompted national discussion when published in 2021. Although the article is likely too long to use in most classrooms, the podcast offers students the opportunity to hear some of the reasoning and examples that make the article so compelling. Treuer’s tone in the podcast is conversational and even humorous, and of his many wonderful points, I’m especially grateful for at least two quotes for students to hear. The first comes when he challenges the notion that humans are separate from nature: “The way that Native people have related to land, you know, we understand that it’s not simply something for us to take from or to set aside, but that we have ongoing relationship with it — that we’re implicated in the landscape, and the landscape is implicated and changed by our presence on it.” This notion of reciprocity between humans and the land, also emphasized in the writings of Indigenous author Robin Wall Kimmerer, offers an important contrast with the “preservation” vs. “efficient use” dichotomy that has defined the U.S. model of conservation since the Progressive Era.

The second Treuer quote I appreciate comes when he imagines how the national parks, and the experience of visitors, might be different if they were returned to the tribes:

I really believe that if you are standing [in Yosemite], looking at Half Dome, and you are standing in awe of this physical thing, this incredible, beautiful, natural wonder, and you recognize that the only reason you’re being allowed to stand there is because that land has been given back to Native control for very specific historical reasons, you’re going to be able to look at that as not just a natural wonder, but you’ll be able to look at it as though you’re looking at the face of this country with a kind of honesty — impossible if we continue business as usual.

This kind of honesty — a historical reckoning with crimes committed in the name of environmental preservation — is exactly what is needed if we hope to nurture an environmental justice movement that can challenge the crises of climate and ecological collapse while simultaneously dismantling the systems of colonization and racial capitalism that have created our current predicament. Treuer’s suggestion that the national parks could become one point of entry into this sort of historical reckoning feels like an invitation to all U.S. history teachers to bring that conversation into our classrooms.