Preview of Article:

Teaching the N-Word

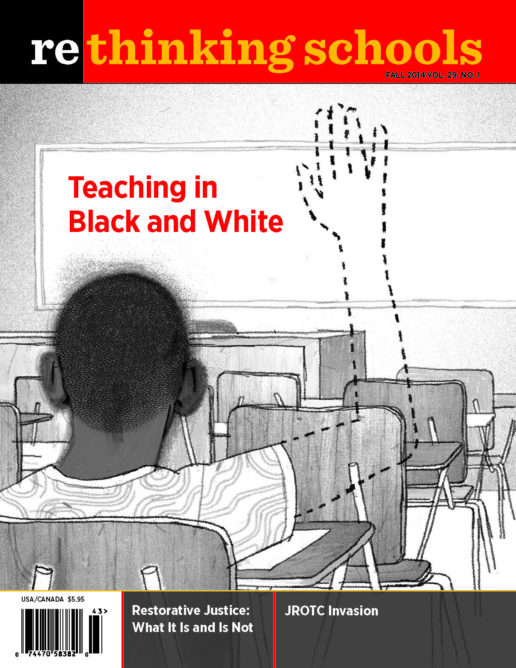

My students—black, white, Latina/o, Vietnamese, and Cambodian—all sighed and rolled their eyes in unison when I asked them to write about the n-word. This was not the first time that a middle-aged, white English teacher in sensible shoes tried to get down and dirty over a sensitive subject.

It was the first day of my unit on Fences, August Wilson’s play about an African American family in 1940s Pittsburgh. Fences was always a favorite with my 10th and 11th graders, but I wanted the class to discuss the use of the n-word before we read and performed the play.

One boy in the back of the room mimicked falling on a sharpened pencil to a chorus of giggles. But eventually the students, all 10th graders, got into the warm-up, and wrote more quietly and longer than usual.

“So, what do you know?” I asked after 10 minutes.

“It was used to describe black people,” one student began in a singsong.

“It’s a derogatory word for black people,” someone suggested. Derogatory was a new word from a previous unit, and it was encouraging to hear a student using it. This was progress.

“It’s a bad word,” another student said.

“No.” José picked his head up from his desk. “It was only bad a long time ago, until rappers started to use it.”

“It’s not such a big deal anymore, Ms. Kenney.” Meredith yawned over a SpongeBob doodle she was drawing on the cover of her spiral.

Thus began our n-word talk, a discussion I have repeated with almost every English class for the past 12 years. Many high school teachers like me, white and middle class, approach the topic with trepidation. I can still remember how my own English teacher, Mrs. Kleeg, addressed the n-word only once, while we were reading To Kill a Mockingbird in 8th grade, and then only after James Parker, the class clown and aspiring pain in Mrs. Kleeg’s butt, raised his hand and asked her what it meant and how to pronounce it. “That word . . . well . . .” Mrs. Kleeg blushed and clutched her pearls. “It’s not a very nice word for Negroes. I don’t suppose I really know the pronunciation.”

I probably would have stumbled down Mrs. Kleeg’s path when I began my teaching career in the Portland, Oregon, public schools if it hadn’t been for a local controversy surrounding the teaching of Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. Several African American students at a mostly white high school objected to the novel, specifically because of the use of the n-word. But even as a novice teacher, I wondered whether the problem in this case was the use of the n-word itself in Huckleberry Finn, or the way many teachers handle it.

I made a commitment to teach my students about the n-word at least once a year. At first, I taught the lesson to avoid offending and marginalizing my African American students, who made up less than 10 percent of the student population. However, over the years, the reaction I got from many of my students convinced me that this was a lesson every student needed to learn.