Teaching the Haibun During Times of Chaos and Struggle

Illustrator: Simone Shin

As I write, fires burn through Los Angeles, leveling homes, schools, businesses, beloved parks. Stephanie Pinto, my former student who teaches art, and her husband, Navin, have lived in Altadena for the last 20 years. They shared a photo of their house that burned to the ground: a charred palm tree, walls toppled and blackened, a soot-stained chimney standing alone, gold Christmas ornaments hanging from a burned tree. Navin’s orange shirt and her daughter’s red coat provided the only spots of color as they stood in the driveway looking at the scorched remains of their home, named Snehalaya, “house of love,” after Navin’s father’s home in Hyderabad, India.

Climate chaos has swung its wrecking ball across the globe: Massive rainfall resulted in flooding in Southeast Asia and along the Mississippi; hurricanes spawned dozens of tornadoes and flooding in Florida; wildfires burned swathes of forests, towns, and cities in California, Oregon, Washington, Australia, Canada, and parts of the Amazon rainforest. Even the mist-covered, rain-drenched redwoods along the Avenue of the Giants in Humboldt County, California, where I grew up, caught fire.

How do we mourn and remember the places we love that we may never see again? Students face the loss of sacred, beloved places when their families are priced out of their communities, divorced, driven to flee because of violence, poverty, forced immigration, and climate catastrophes. When I visited Kjerringøy, Norway, birthplace of my grandfather, William Christensen, who fled his family’s poverty, I wondered what this silent man took with him from home? Fjords? Pastures? The midnight sun? Swimming in the Norwegian Sea? His mother’s krumkakes? The sound of his language?

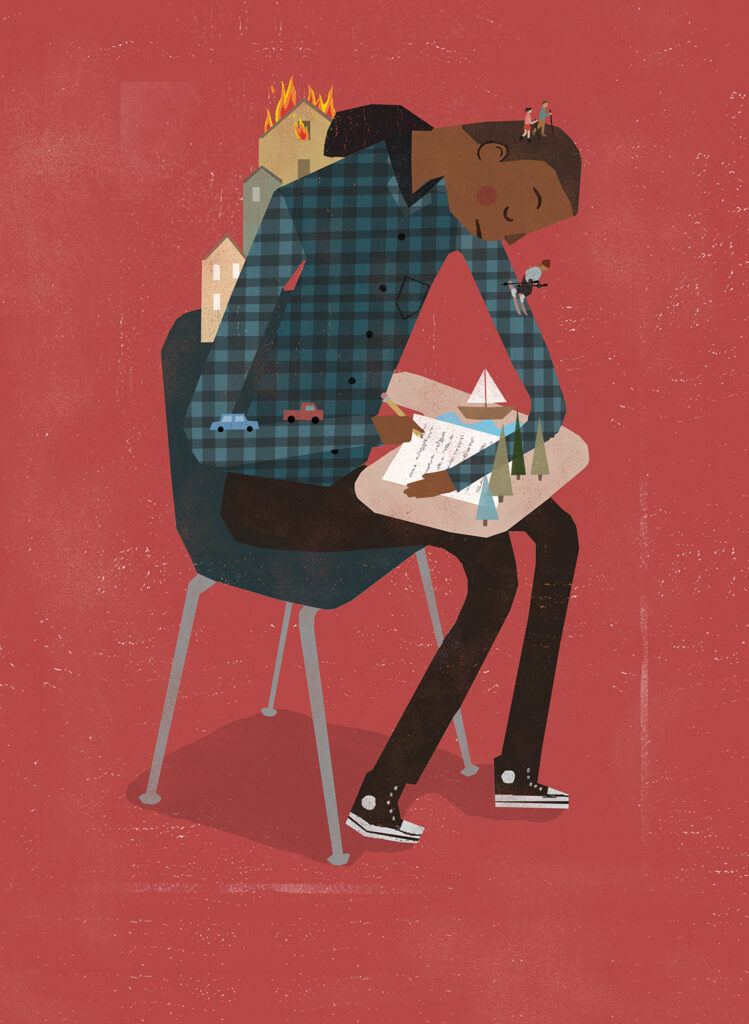

Writing about sacred places has been a consistent practice in my classes for years, because the pieces students write build a safe memory, help create classroom community, and also give me a passage into their lives, so I can know them better. But as the world catches fire, we need to find ways for students to hold on to the places they love, to recreate them in words, to carve the images and feelings in their memories, so if and when chaos visits, they can close their eyes and recall a place they love. When my body has absorbed too much of the world’s pain, I tilt my head back and recall my father’s hands on mine as we row across Humboldt Bay. I feel the waves lapping against the side of the boat, the briny smell of the bay, the gulls skimming the water, the fog like a misty coat shrouding us on our journey.

As the world catches fire, we need to find ways for students to hold on to the places they love.

Teaching the Haibun: Listing

This year, I have the great fortune of co-teaching with Dylan Leeman, an incredible 10th-grade language arts teacher and a beautiful soul who I had co-taught with two decades ago. Knowing that the year would be filled with election mayhem as well as books and ideas that deal with the tough topics of injustice in all its ugly forms, we chose to center our opening on joy, to remind students of all that is beautiful in their lives and their world. Teaching about joy, love, and beauty in social justice education is not a denial of hardship or tough truths, it is an intentional choice to demonstrate that even during the hardest moments, people find ways to also hold on to their humanity by bonding with others through laughter, storytelling, and gratitude for the beauty in the world.

Dylan and I decided our first writing of the year had to be an easy lift — an opening that provided us with an opportunity to learn about our students’ lives and writing skills while also introducing them to each other. We chose a haibun, a Japanese poetic form that combines a prose descriptive paragraph with a haiku. Basically, the haibun is the coming together of ocean and shore in writing, a way of remembering an evocative location that provides us with a sense of peace and love.

We began by asking students to make a list of places they love. We salted the pot by throwing in neighborhood spots in our introduction: “Make a list of the special places you love, places that bring you joy, peace, or happiness, places that you want to sear into your memory for the days when you need a safe or sacred place to recall: Church, your grandmother’s basement, the Sellwood docks, Oaks Park, the football field, the dance studio, Irving Park, Grant pool, the library.”

Dylan’s room has eight tables with four chairs per table. Students filled every chair. Grant High School has 2,100 students, who come from multiple middle and K–8 schools, about 30 percent students of color. Most, but not all, of the student body live in economically comfortable households. Although some students knew each other, many were strangers we hoped would become friends, or at least academic partners. If students were going to share ideas and engage in group discussions throughout the school year, we needed them to feel comfortable with their classmates. In a class this size, speaking up can be terrifying for some. Our opening list was for their haibuns, but also worked as a conversation starter. After they listed, we said, “Share your lists with your table group. If someone mentions a place that you also love or that reminds you of a place you love, add that to your list. Your group will share five special places with the class.”

Instead of losing students with an elaborate description of the haibun, we sketched a quick definition, then jumped in with models that we’d both written. The easiest way to bore and lose students is to begin with a lecture. Also, by sharing our writing, we demonstrated that we, too, were writers and we could teach them through our pieces instead of through technically elaborate speeches.

We asked them to notice both the content and the style in our writing: What did we write about? How did we write about it? What writers’ tools did we use? These questions would become a thread throughout the year as we taught students to think about writing as writing detectives: How did the writer do that? What literary techniques did they use?

If I was working with students experiencing the trauma of immediate loss, I might have chosen to share my piece about picnics on the Van Duzen River, near the Avenue of the Giants fire. But instead, for our opening, I shared a haibun I wrote about Cannon Beach, the closest ocean shore to Portland, which would be familiar to many students.

On the days when tourists don’t crowd Cannon Beach with their candy-striped umbrellas, their carts filled with food and kites and buckets, pelicans land on Ecola Creek, hundreds of them, brown wings bowing to the creek’s white-capped dash into the Pacific and the elk run at the edge of the ocean, hooves kicking up plumes of sand until they eclipse the horizon. When the tourists leave, taking the smell of taffy and sugar cones, when the sea is left to ponder the thicket of reeds where the red-winged blackbirds sing, when sand dollars slip back into the ocean’s white foam untouched by human hands, the waves unfurl again and again, despite the hurt and anger and mess of the world, washing the day with a patient blessing.

The open palm of dawn

slides sun from Saddle Mountain

soothing the sea’s rumpled back

Before asking students to share out in the large group about their observations, we asked them to talk about my piece with their group members. We hoped that more students would talk if they had confidence in their ideas. Mostly, during the large group debrief, students noted lines that they liked. Of course, there was a flurry of discussion of their own memories of flying kites, roasting marshmallows over driftwood fires, Bruce’s Candy Kitchen where they buy taffy, but they also noticed the way I described both the pelicans and the elk. After their comments waned, I moved to the whiteboard where my haibun was projected and underlined my use of repetition with the when clauses (when the sea is left to ponder, when the sand dollars . . .), and the repetition of sounds (sand dollars slip, soothing the sea’s) — two writer’s tools we focused on during the writing assignment.

Unfortunately, most students are not given the opportunity to write wildly without judgment — to discover and articulate their own insights instead of parroting their teachers or textbooks.

Drafting

William Stafford, Oregon’s fourth poet laureate, wrote, “If I am to keep writing, I cannot bother to insist on high standards. . . . I am following a process that leads so wildly and originally into new territory that no judgment can at the moment be made about values, significance, and so on. . . . I am headlong to discover.” Unfortunately, most students are not given the opportunity to write wildly without judgment or standards to new and original thought — to discover and articulate their own insights instead of parroting their teachers or textbooks. When Dylan and I met at Fleur de Lis Café in August, to discuss co-teaching, our ideas were animated by the possibility that we could make Stafford’s quote a core piece of our work for the year. Students would write a lot — in multiple genres, with multiple drafts, learning the craft of writing. They would write and share their work in class. When we started writing haibuns, we knew that it would take at least a week, maybe two, so that we could coach them from listing to revision to sharing to reflection.

We moved into the writing by asking them to select one place from their list. “Now, close your eyes and take yourself back to that spot.” Over the years, we have found that pausing to evoke memories and solicit details helps students, especially reluctant writers, slip in to the movie of their special place. We stopped between each prompt to give them time for the details to rise up instead of rushing through them all at once. “Remember what your place looks like.” Then students wrote the details in their notebook. Although it is time-consuming, we asked students to share their initial list to help other students shake loose more specifics and to help those who struggle know what we’re asking for. “Listen to your table mates’ descriptions. Which ones help you visualize their place? What else would you like to know?” We proceed through smells that evoke memories of the place (pine trees, hamburgers, incense, sweat). Sounds. People. Action (diving into the lake, dancers bending along the ballet bar).

Then we said, “Write the first section — a description of your place — include sensory details and language specific to that place. Write fast. Make mistakes. Just try. It doesn’t have to be great. It’s a draft. If everyone is still writing and you feel like you are done, skip a line and write another memory that came up.”

Revising While Drafting

After reading their drafts, Dylan and I noted that most were bare bones. Students wrote about skiing on Mt. Hood, jumping off the docks into the Willamette River, or sneaking out and sitting on a pedestrian overpass to watch the city lights. Skimpiness was not unexpected. After all, this was the first assignment of the year. But our goal was not just this piece of writing, it was to build their writing skills by teaching them the tools that writers use. Over the course of the year, we hope that these revision tools will become internalized, something they return to in all genres of writing.

The following class period, we encouraged students to play with their initial drafts, to expand them, make them bigger, more detailed. On the slide deck, I showed my first, second, and third handwritten drafts — the crossouts, the arrows, the new piece written below the original — to encourage them to be messy and playful, invoking Stafford’s wild writing.

For this first revision, we also harvested examples from student pieces that exemplified the writing strategies we wanted them to add to their next draft. Using classmates’ writing also signaled that we read their pieces, took them seriously, and that we consider everyone in the class a teacher. Our handout noted the tools their classmates employed:

After you read each of the following pieces, re-read your piece. Grab a new piece of paper and work on a revision: Add strong verbs. Add delicious details. Add short sentences.

In the following section of Eli’s piece, notice the use of several writing strategies. Where could you add repetition, short sentences, strong verbs?

Years-old trees tower over the meadow, echoing each kid’s voice. [Note the strong verbs — tower and echo.] Current voices. Past voices. And all the future voices. [Note the intentional use of fragments.] The smell of pine fills the kids’ noses with nostalgia. Sounds of games fill the kids’ ears. T-shirts and shorts fill the kids’ vision. Days feel quick; nights feel quicker. [Note the repetition to create rhythm and evocative details.]

Notice Zora’s use of repetition to create a rhythm:

It’s days at the docks with the boats and my folks [note the internal rhyme of boats and folks] that make me want summer to never end. Days at the docks with the sun and my swimsuit that make me want to stay here forever. Days at the docks when the water is calm and the sun shines make me realize the little things that matter. [The repetition of days at the docks creates a rhythm in Zora’s piece.]

Then we returned to a drafting/revision process: “In the prose section, you might play with these poetic elements. Go back to your piece and add sensory details. Make the reader see, hear, and smell the library, dance studio, forest, or park.” On a projected slide, we wrote:

- Use all the senses. Help your reader see, hear, and smell the place you are writing about.

- Play with line length — a long sentence followed by a fragment, series of fragments, or short sentences. Think about beats in music.

- Repeat a sound. Repeating a letter — the moon shone silver across my satin sheets.

- Repeat a word or phrase. Again, think about music and the way a repeating word or phrase creates a rhythm in the poem.

After each round of drafting, we had them color-highlight their changes, additions, and share with tablemates.

The Haiku

The haibun ends with a haiku that relates to the prose poem but doesn’t need to summarize it, rather it partners or reflects ideas from the first section. Dylan gave students a quick review of the elements of haiku by returning to our haibuns and generating a list of haiku “rules” with them. Most students were familiar with the poetic form and had written haikus at some point in their earlier years.

They developed a definition or rules: A haiku is made up of three lines: the first line has five syllables, the second line has seven syllables, the third line has five syllables, for a total of 17 syllables. Students had fun, tapping out the syllables as they wrote, consulting with their table mates — or friends across the room — to find words with the right number of syllables for their haiku. Dylan and I weren’t concerned about correctness; we just wanted them rowing in the right direction. By the end of the period, most students wrote a haiku to complete their haibun.

Writing Like a Writer

To build stronger writers, we pushed students to notice, name, and discuss the changes they made, to become fluent in the language of writing and revision, to overcome the “one and done” drafting, the “good enough” mindset that we’ve observed in too many students.

Once our students completed their draft with all the additions, they typed a clean copy on the computer. “Writers make changes in their drafts. You might continue to revise as you type. Keep track of the changes you make.” Once they had their typed draft, we told them, “Highlight any changes you made. Number each change and write notes in the margin about what you added or changed and maybe why. Did you add alliteration? Longer or shorter sentences? A list?” Dylan modeled this process by sharing his numbered and highlighted draft with marginal notes on his Google document, demonstrating how he added notes about the changes he made by inserting a comment in the margin.

After students numbered and highlighted and wrote marginal notes, we asked them to take out their notebooks and look at their first and final drafts, as well as their notes about changes, and to write an analysis of what they changed and why, and what writing strategies they will take with them to their next piece of writing.

Students shared their insights about writing and revision with their table groups and the class. Stephanie talked about making her haibun more concise by getting rid of filler words like “the” and adding repeating phrases to create a rhythm. Reading his first draft, then his revision, Ian showed us how he added more detail about the dock, so readers could visualize it. “I learned ‘less is more’ sometimes,” Iris said. “Also, that descriptive words are powerful, and that when you cut filler words, strong verbs stand out more.”

We followed this by having them create a poster of what they learned or practiced about writing that they will take to their next piece, telling them “Use at least one example from each student at your table.” Students hung their posters on the hallway outside of Dylan’s room. We ended class by giving students sticky notes so they could comment on the posters. These posters still hang in the classroom as reminders of what they know about writing.

Sharing and Collective Text

On our final day of the haibun lesson, each student created a slide with their haibun on the class slideshow. Because of time constraints as well as the knowledge Dylan had about some students’ anxiety, we had students share their haibuns in table groups instead of our usual read-around. Building a safe community is not a one-time activity; students will share their writing and ideas in every lesson throughout the year — building toward a classroom where students gain confidence to share their lives as well as grapple with tough issues. “Today you will share your haibun. Each student will read their piece as their partners read along on their own screen. Partners will look for what is great in the writing.” Our instruction slide read:

BE SPECIFIC! “Good flow.” “I like the words.” are not specific.

Specifics might be:

- I like your repeating phrase . . . (then say the phrase)

- I like where you repeat sound combinations

- I like the verbs xx, xx, and xx

- I like that you wrote about your day at the mountain and how you talked about carving the hill. I could feel the cold and hear the gears when you read . . .

Once they shared, we asked them to read haibuns from five other classmates and write a specific, positive note to keep the writer writing. Dylan and I filled in if some students didn’t have notes.

Because one of our aims was developing community in the classroom, we finished the haibun lesson by asking students to write what they learned about their classmates from this activity: “Now that you have listened to your classmates’ haibuns, think about what you learned from each of their experiences. ‘Read’ the collective text of our classroom: What sacred places do your classmates love? Then write a summary paragraph, referring to your classmates’ pieces for evidence.”

The first part of Sarah’s collective summary echoed what many students wrote: “Throughout this lesson I learned most of us enjoy their families and nature.” I loved her final sentence because it voiced Dylan’s and my intentions for the project: “I also learned more about these people who were previously strangers.”

As I think about the fires in Los Angeles and our students who experience loss in all its manifestations, Anna’s words about the lesson stand out: “I’ve learned that everyone has a special place, whether it is a house, a lake, a game. Everyone has a unique place, but each of our places gives us comfort.”

Writing a poem doesn’t bring back a home, a forest, a city, or a park, but everything we do in our classroom should not only teach students about the world, and the skills and tools of our content, but should build stronger, more resilient, kinder human beings. How do we make strangers into friends? How do we teach our students to savor their sacred places, so they can return to them and find moments of comfort during times of stress and chaos?