Teaching the Fight for Queer Liberation

“Queerness and its history was a mystery to me and when you are told so many times that a ‘concept is new’ you believe there wasn’t much beforehand. . . . What I didn’t know was that there is so much more to queer history than what is visible in the present.” After finishing our simulation of the strategic dilemmas that queer movements faced in the 20th century, Stone reflected on the curricular silence many students experience. All students, queer students in particular, deserve to encounter this history so that they might develop a fuller sense of self, examine how questions of gender and sexuality have shaped their present, and imagine where our society might go next.

Today we are experiencing a countermovement in response to recent progress on gay rights. The ACLU tracked 533 anti-LGBTQ+ bills introduced in state legislatures across the United States in 2024. Twenty-one states restrict or explicitly censor discussion of LGBTQ+ people or issues in the curricula.

For students to imagine challenging today’s attacks on LGBTQ+ rights and building queer futures, they need to reach back into our collective history and learn from those who fought these same forces that would punish, pathologize, and erase queer people.

“You Are Participants in the Growing Fight for Queer Liberation”

Pedagogically inspired by Bill Bigelow’s abolition movement role play and Adam Sanchez’s Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee role play, I wrote a dilemma-based, problem-solving simulation in which students imagine themselves as participants in the fight for queer liberation. Role-playing movement participants, students debate key questions regarding the goals and strategies that organizers faced from the 1950s to the early 2000s.

Having taught Bigelow’s and Sanchez’s simulations in my African American History classes, I knew that I wanted to teach LGBTQ+ movements in my Queer Studies elective with a similarly interactive, problem-posing approach. In their role plays, students took on the role of an activist in one key movement organization and debated important questions that organization faced. With books and articles spread across my table, I was unsure of which organization to select for the role play. No LGBTQ+ organization emerged as an obvious choice given my desire to capture decades of movement-building. I decided to center the simulation around the evolving movement as a whole, not a single organization. This broader scope would enable students to recognize how the work of liberation in an earlier era can lay the foundation for later activists.

I taught this simulation in Queer Studies, an elective I designed with students, and my 20th-Century Social Movements class. At the academically intensive public magnet school in Philadelphia where I teach, the juniors and seniors in my Queer Studies class are a breath of fresh air, developing a sense of community because they made the choice to be there. My school has a racially diverse student body, though not reflective of a district where more than 70 percent of the students are Black and Latino. Although the activity feels different in Queer Studies where nearly every student identifies as LGBTQ+, many straight students in my other class are eager to participate, motivated to be better allies and more informed given ubiquitous discussions of gender and sexuality in their lives.

We began by reading aloud the “Joining the Growing Movement for Queer Liberation” handout that introduces the simulation:

In the 1950s, you join the emerging homophile movement, which seeks to support gays and lesbians during the Cold War era when your community is facing increased hostility, policing, and discrimination. In the decades preceding World War II, diverse same-gender sexualities and gender nonconformity increasingly found expression.

The handout describes romantic friendships, Boston marriages, pansy clubs, drag balls, “womanless weddings,” queer rural life, queer urban life, the role of the New Deal, World War II, and the Cold War, and finally the Lavender Scare.

Memoirs of Early 20th-Century Queer Lives

After we read the “Joining the Growing Movement for Queer Liberation” handout, students wrote memoir vignettes from the perspective of a character of their creation placed in a real historical context. This assignment engaged students in building the context out of which the movement emerges. I explained to them:

Before we begin a decades-long journey fighting for freedom and dignity for queer communities in the United States, you will look back on life before 1950. Your memoirs will tap into these experiences before and during the earliest years of the Lavender Scare. Your memoir must describe your character’s motivation for joining the growing movement in the 1950s.

I wanted this assignment to help students appreciate that movements are complex amalgamations: responses to ongoing conditions, particular catalysts, and prior resistance. To support diverse and accurate representations of queerness, I asked students to revisit the initial handout:

In creating your character, remember to use real historical context from the “Joining the Growing Movement . . .” handout. There, you will find glimpses into urban and rural queer lives, Black and white queer lives, and more. Which context did you find compelling? Choose one and review the source I provide for that context so that you accurately depict your character.

After students finished their vignettes, they read them in pairs or groups of three. This provided a chance for students to share their writing and get in the mindset of the time in which the first strategic question emerges.

In Cameron’s excerpt, she imagined what might motivate the fictional Marianne Freeman to take action:

The earthy scent of dusty old books consumed the air. . . . Within the ever-growing chaos of the world, the walls of the old corner bookstore are where I find solace. . . . I’ve been keeping a big secret for as long as I can remember, a secret that could now ruin my life. . . . Nancy Moore has been a source of dilemma for me for quite some time, yet someone I’m so sure about. She is dear, kind, caring, and easy on the eyes, so much so that I think — no, I know — that I must have become infatuated with her the first time her soulful eyes gazed upon me. She must have felt something, too, considering this somewhat indecent arrangement we’ve had for quite some time. . . . How come our affection for each other has to remain a secret?

This dawned on me as I continued reading through Alfred Kinsey that my deeper attraction to women, and specifically Nancy, is not uncommon. . . . I became enraptured in Kinsey’s description of a Black church in the South where same-sex love could flourish as an open secret. This lifestyle is something I long for.

Strategic Dilemmas in the Fight for Queer Liberation

In the simulation, students engaged in six strategy meetings. Each revolves around an actual strategic dilemma the movement faced during a particular time. Although I did not instruct students to engage in these strategy meetings through their character’s point of view, I always have a student who asks. I tell them that they are not required to but can if they want to.

The dilemmas:

- In the 1950s, students imagine themselves as members of organizations forming amid the Lavender Scare. They debate the first dilemma of the modern movement: Should the Mattachine Society and Daughters of Bilitis remain secretive or operate publicly? Why?

- In the 1950s and ’60s, being queer in public becomes more dangerous with an increase in entrapment, job discrimination, and police raids of queer spaces. The Washington chapter of Mattachine wanted to fight to repeal anti-gay policy, but the national leadership insisted that they limit their activities to research and education. Students debate: Which strategy or strategies should the Washington chapter of the Mattachine Society adopt and why: a) providing a social space and education to gay communities; b) sponsoring research that proves gay people are not criminal or diseased; or c) changing unjust laws and protesting for civil rights?

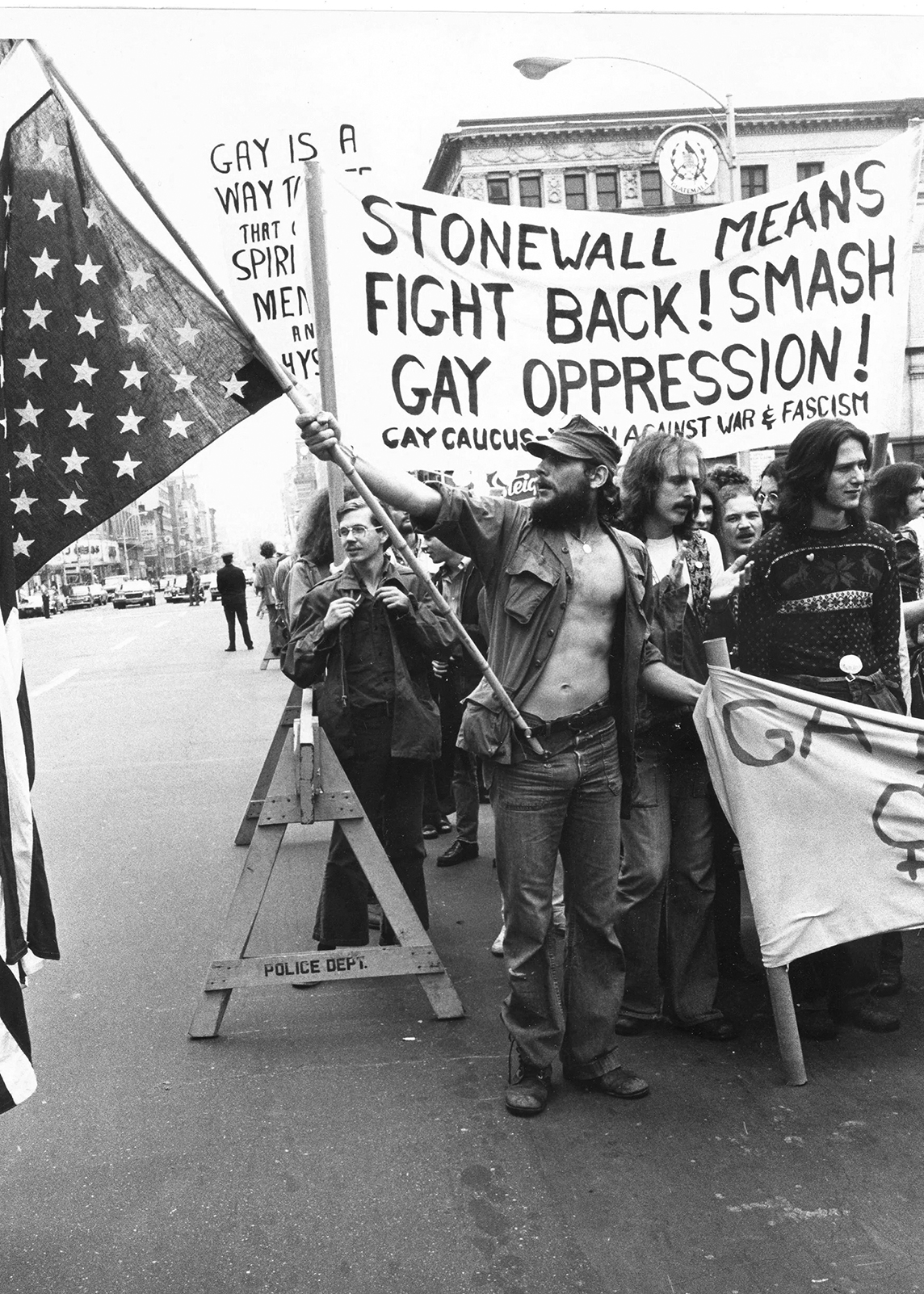

- In the wake of the Stonewall riots of 1969, some gay people wanted to demonstrate in support of the Black Panther Party members jailed under false accusations in the Women’s House of Detention, 500 feet from the Stonewall Inn. Others opposed this. This disagreement was representative of a broader debate among gay people about how to interact with New Left organizations that at times perpetuated homophobia. Students debate: Should your gay movement organization endorse a demonstration in support of Panthers incarcerated in the Women’s House of Detention? Come up with three talking points to explain to the press why you are or are not endorsing.

- In the late 1970s, the movement faces a well-organized anti-gay crusade funded by the Religious Right. In California, state senator John Briggs proposes Proposition 6, which would empower school districts to fire gays and lesbians and anyone presenting homosexuality positively. Opposition to Prop 6 is divided between the more confrontational Streets and the more respectable Suits. Students debate: Should the anti-Briggs campaign mobilize Californians to vote no on Prop 6 by adopting a rhetorical strategy that directly addresses gay identity or should it address the issue of privacy and avoid talking about homosexuality?

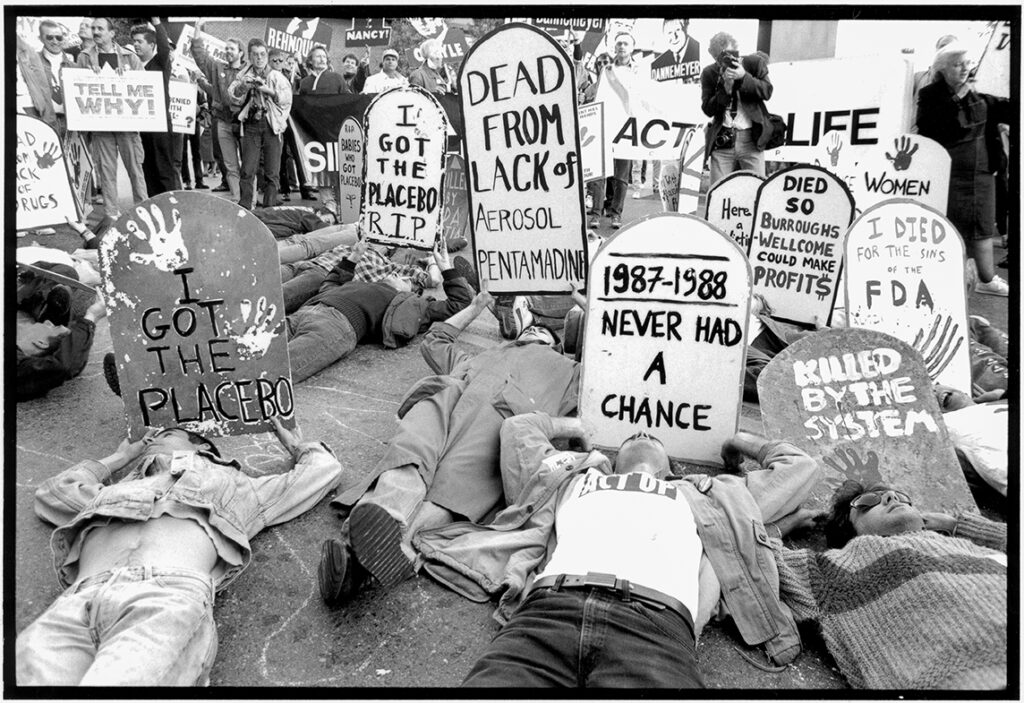

- In the 1980s and ’90s, ACT UP, AIDS Memorial Quilt, and Gay Men’s Health Crisis among others form to address the HIV/AIDS epidemic during a time of severe government neglect. Students respond to the following prompt: Where would you dedicate your limited time and energy? And why? a) direct service to those with HIV/AIDS, b) counter-memorial commemorating those dying from HIV/AIDS, or c) direct action approaches to ending the AIDS crisis?

- In the 1990s and 2000s, Bill Clinton makes a campaign promise to end the military’s ban on gay and lesbian personnel. Same-sex couples sue for the right to marry in Hawai’i, Clinton signs the Defense of Marriage Act, and wealthy gay donors offer large sums to organizations to prioritize same-sex marriage. Are these opportunities or traps? Students debate: Should movement organizations prioritize gaining access to mainstream institutions like marriage and the military? Why? If not, what should they prioritize?

Although I designed the dilemmas to build on each other, a teacher could engage students in a particular dilemma or set of dilemmas. Any of the dilemmas and their historical outcomes could work on their own, but the second dilemma assumes some prior knowledge from the first.

In my Queer Studies class, I facilitated the first strategy meeting because this was students’ first time doing a simulation like this. With the desks arranged in a circle, students popcorn read the dilemma’s overview:

As the Cold War developed in the late 1940s and 1950s, the U.S. government began firing gay employees hired during the New Deal expansion. Government officials justified this purge by arguing that Soviet spies are blackmailing gays and lesbians into providing compromising information. Tasked with investigating this claim, the investigations subcommittee of the Senate’s Committee on Expenditures in the Executive Departments (also known as the Hoey Committee after its chairman, Senator Clyde Hoey) issued a report concluding that

homosexuals and other sex perverts are not proper persons to be employed in government for two reasons; first, they are generally unsuitable, and second, they constitute security risks. . . .

The purges that followed, called the Lavender Scare, affected between 12,000 and 20,000 federal employees suspected to be gay or lesbian. In response to these purges and increasing police raids on gay and lesbian bars, the first gay and lesbian organizations formed, known as homophile organizations.

By chairing the first meeting, I modeled for students how to ask follow-up questions, how to prioritize those who haven’t spoken, and how to bring the strategy meeting to a close by holding a vote on the proposals that came up in open debate. During the first strategy session, students debated whether the Mattachine Society should operate secretly or publicly:

Samia: If our group stays secret, we can’t contribute to social change. We can’t influence anyone. Can the group be public but anonymous?

Adrian: I disagree that secret groups can’t contribute to social change. We don’t need to be seen by others, just each other. Being in secret is an act of resistance and we can get bigger, maybe big enough to make change later.

After other students chimed in on whether secrecy prevents social change, I asked the group to reconsider Samia’s idea:

I love this debate about secrecy and social change. I wonder if we need to return to the question Samia raised earlier: Can the group be public but anonymous? What do you think this would look like for our organization?

Students picked up on the thread:

Ellie: Some people in the group could be doing public advocacy but others could stay secret, hosting parties for gay people.

Serafina: What if we did graffiti or published gay people’s stories but anonymously.

Bailey: Ooh, we could do a magazine! So we are public but not with any of our names.

Adrian: I like that but how do we maintain protection as we grow?

We were approaching the end of the period, so as the meeting chair, I raised the two original options and the third option that emerged in debate.

Let’s vote! Choose one of the three options: 1) Declare ourselves publicly; 2) Remain secret without any public actions — anonymous or not; 3) Develop a public-facing initiative that protects members with anonymity.

Students voted for the third option by a slim margin.

Directly following the strategy meeting, students read about the historical outcome of the debate they had just engaged in. This allowed students to learn what really happened while their own proposal and decision-making was fresh in their minds. The historical outcomes also helped to establish some of the context for the next dilemma. In this case, students found out that the debate about whether to remain a private organization or push publicly for political reforms was just as contentious in reality as it was in our classroom. The dispute split the Daughters of Bilitis and even the members who pushed for the group to be more public used pseudonyms in their newsletter to protect their identities.

Next I asked for student volunteers to chair the strategy meetings for the second, fourth, and sixth dilemmas, which all take place in a circle with the entire class. I dedicated a full 45-minute class period to each strategy meeting. To share responsibility, I selected a different student or pair of students for each of these meetings. Although students might bring their own style to chairing the meeting, most continued the format I had established: popcorn read the overview, read the question, quietly read the arguments, open debate, lift up proposals, hold a vote, and read the outcome.

Students need space to work out their ideas in community. Beyond learning about the fight for queer liberation, by engaging in this kind of debate, students learn how to talk with one another to problem-solve and make decisions that matter.

Students discussed the third and fifth dilemmas in small groups. Breaking up the large group format enables more reticent students to talk with more frequency. For the fifth dilemma, I told students not to debate the options — direct service, counter-memorial, direct action — but rather to share which one they would dedicate their limited time and resources to as an individual during the AIDS crisis and why. This gives them a chance to see where they might fit in the broader landscape of addressing injustice without counterposing different tactics.

Lessons Learned from the Fight for Queer Liberation

After completing the simulation, I asked my students:

Draw the shape of the history represented in the simulation from 1948 to 2015. Your shape may be metaphorical or more mathematical, like a graph. Think creatively here. You might consider the shape of progress, retaliation, movement goals, or the dynamics of inclusion and exclusion.

Drawing two footprints forward and one footprint backward, Isa wrote:

On the road toward progress, the journey forward is often accompanied by retaliations, circumstances, or mistakes that cause movements to backslide before moving forward again. As gay and lesbian movements acquired success, the Religious Right began coordinating backlash against these movements.

Lena made a similar observation:

I believe that the shape of the progress of queer liberation over time is not linear and fits more of the idea of a “loop de loop,” where after rapidly moving forward, the movement is taken aback before returning to the track. For example, in the 1920s, while people would not verbally state that they were queer, open secrets about queer identities were common such as the gender-bending performances of Gladys Bentley and rise of queer artists, however, once the ’50s hit, in came the Lavender Scare that sent queer communities back for decades to come. Queer communities were forced to repress their identities before “bouncing back” with groups like the Mattachine Society.

When students realize that the shape of progress is not linear and countermovements form to threaten prior gains, they not only debunk the myths of progress, they prepare themselves for the need to protect freedoms previously won.

Depicting hands pulling, squeezing, and grasping the “shape” of history, Amari described his powerful vision of agency about who is included or excluded from the LGBTQ+ movement:

The hands of those who participate in history are the ones that manipulate it. They choose the amount of inclusion, exclusion, and progress that is made within a movement. [For example,] the formation of Radicalesbians brought forth a new interpretation of the shape, expanding it to include lesbians and cis women, but narrowing it so that trans women were not included in their activism.

Delia made a similar observation:

Early on in America efforts to decrease the strife of LGBTQ+ individuals led to an emphasis on assimilation . . . that meant condemning those within their own community who were further from the norm to shift the window of acceptance to sparingly include non-heterosexuals, but only those willing to conform. There’s a tendency to want to be seen as respectable even if it means holding yourself above those who are struggling.

After drawing and writing about the shape of queer history, I asked students to write a current-day strategic dilemma, applying what they learned. Here are a few student examples:

- Should gay organizations prioritize LGBTQ+ visibility in advertising and marketing?

- How do we help with issues that transgender individuals face with health care?

- How can gay organizations effectively resist “don’t say gay” bills attacking LGBTQ+ students and curriculum in schools?

- In the face of anti-trans legislation, do we as an organization prioritize protesting in the streets, creating safe spaces for trans children, or affecting legislation directly such as lobbying and legal movement?

Lastly, I asked students to facilitate their dilemmas in small groups. In her reflection on the last question above, Sarah wrote:

Throughout all of the situations, there are recurring conflicts. Everything traces back to one question: attempt to tackle the root cause or focus on relieving the symptoms? The difficulty does not lie primarily in uniting toward a common goal, but in uniting toward a common method for achieving that goal. Is it worth it to form alliances with organizations with interests that parallel your own despite those groups refusing to recognize you as equals? Should we focus on working within existing systems and repairing their flaws or tear down the institutions and start from the ground up? Safe spaces or street protests? Progress seems to move like waves, sea foam creating against the sky only to crash into the sands and be dragged back into the depths. But over time, the tide rises.

By engaging in these strategy meetings and developing historically informed questions, my students learned to appreciate that ordinary people like themselves can come together to build a more nurturing and just world.

Definitions of Terms

| ACT UP | AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) formed in 1987 with the mission to use direct action to end the AIDS crisis. |

Boston Marriage | As more women gained access to education and professional careers, some avoided heterosexual marriage and elected instead for relationships with other women in what were known as Boston marriages. |

| Daughters of Bilitis | Four lesbian couples in San Francisco formed the Daughters of Bilitis in 1955 to organize secret lesbian social gatherings and avoid police harassment and arrest. The group soon launched a newsletter and began public advocacy for legislative change. |

| Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) | Signed into law in 1996, DOMA defined marriage as between a man and a woman and denied same-sex couples federal marriage rights even when they lived in a state recognizing their right to marry. |

| Homophile Movement | The homophile movement refers to organizations and publications representing gay and lesbian people in the 1950s and early ’60s. Some at the time considered the term homosexual to have negative connotations, so the term homophile was intended to emphasize gay community and not just an individual’s sexuality. |

| Kinsey Report | The Kinsey Report refers to Alfred Kinsey’s 1948 publication, Sexual Behavior in the Human Male. Based on Kinsey’s research, the book posits male sexuality as incredibly diverse. In normalizing same-sex sexuality, the book fostered a gay political consciousness. In 1953, Kinsey published a similar volume focused on women. |

| Lavender Scare | As the Cold War developed in the late 1940s, the U.S. government began firing thousands of employees suspected to be gay. Government officials justified this purge, arguing without evidence that Soviet spies blackmailed gays and lesbians into providing government secrets. |

| Mattachine Society | Harry Hay formed the Mattachine Society in Los Angeles in 1950, initially using a secret cell structure he learned from his membership in the Communist Party. The group went national, challenged entrapment cases, and engaged in research and education to promote the normalization of gay people. Some chapters went against the national organization’s agenda and sought to promote gay rights through legislative change. |

| Pansy Clubs | Pansy clubs and drag balls became popular in cities like New York and Philadelphia during the prohibition era. They included gender-bending floor acts, like those of Gladys Bentley and Jean Malin. By 1933, the New York police commissioner stationed a cop at the door of every known pansy nightclub, preventing female impersonators, as they were known, from entering. |

| Romantic Friendships | A socially accepted type of same-sex relationship in the 1800s and early 1900s, permitted a certain degree of same-sex intimacy even for people within a heterosexual marriage. |

| Stonewall Riots | The police regularly raided gay bars, including the Stonewall Inn. Stonewall catered largely to poor, young gays and trans folks, clientele excluded from some of the “respectable” establishments. When the police con- ducted a routine raid on the night of June 27, 1969, people fought back. Stormé DeLarverié, a Black biracial butch lesbian and drag king, resisted arrest and punched a police officer as she was taken to the police car. There were several nights of riots following the raid, referred to in New York papers as the Stonewall uprising. In the wake of these riots, organizations like the Gay Liberation Front formed to inject greater militancy into the movement for gay liberation. |

| “Womanless Weddings” | The fundraising ritual of the “womanless wedding” provided readily available public cover for cross-dressing. Starting in small towns across the South, men played the roles of everyone at the wedding, including bridesmaids, flower girls, and the mother of the bride. Although these were comic events to raise money for churches and civic organizations, some attended them as the only chance to cross-dress in public. |

Handouts and Materials for the Queer Simulation Role Play are posted at the Zinn Education Project.