Teaching Social Activism in Prison

Manson Youth Institution is a maximum security correctional facility for adolescent males tried and sentenced as adults in the Connecticut Department of Correction. Its population is composed mostly of poor men of color with histories of abuse, detention, and truancy. Education is mandatory for the majority of Manson’s inmates: boys file up to school — right side of the yellow line, no talking, IDs out, shirts tucked, heads down — bearing the anger, frustration, fear, and loneliness that inheres to incarcerated life. The negativity is palpable; it can overwhelm staff, including teachers. Most days, there are multiple heated altercations (sometimes physical fights) on the school line; students enter class irritated, refusing to work. It’s here, in Manson’s High School Program, where I have taught English for 20 years.

In the summer of 2016, I attempted a special course called “Teaching the Political Manifesto.” For our purposes, I defined “manifesto” as a declaration of political vision and desire. We analyzed historical and contemporary examples, such as David Walker’s Appeal (1829), the United Negro Improvement Association Manifesto (1926), the Port Huron Statement (1962), the Black Panther Party’s Ten-Point Program (1967), and Ralph Nader’s Concord Principles (1992), noting commonalities in structure including the use of “policy points” as a framing device. My goal was for students to join me in thinking about how the literary form of manifesto makes a certain type of political thinking possible, but also about the genre’s limits. Our touchstone text was the Leap Manifesto, a Canadian call to action that sees transformative, justice-based action as the only legitimate response to severe global warming. This document developed from a two-day conference held in Toronto in the spring of 2015. Attendees represented a cross section of Canada’s activists working on Indigenous and labor rights and on environmental and social justice. I chose this text because unlike other manifestos we studied that summer (ones that more directly engaged with matters of race and policing), the Leap centered on a threat that my students knew very little about. It was my hope that they might connect the climate crisis (and its democratic openings) to other forms of injustice they were more familiar with.

The Leap Manifesto has 15 demands, including that governments end subsidies for the fossil fuel industry; invest in decaying public infrastructures; support localized, ecologically based energy systems; and grant protections for all workers, immigrants, refugees, and Indigenous peoples. To understand these demands and the threat of global warming, especially to the poorest of the world’s people, students needed to learn about social policies, corporate and governmental practices, and racist histories that are responsible for the present climate threat but also, in many respects, for their blighted communities and decimated lives. This complex history (particularly capitalism’s legacy of exploiting and monetizing natural resources, labor, time, and human bodies) surfaced in each of the manifestos we read. When students compared historical texts such as the “Black Manifesto” (1969) and the Combahee River Collective (1974) and their calls for racial justice, political liberty, and human rights with the demands and hopes of the Leap, they came to recognize the opening that political and ecological crisis can provide. In this way, students were in step with Leap’s authors, who also see the total and worldwide energy transformation that climate change necessitates as providing an exceptional opportunity to reconstitute the world.

Perhaps because of the timely nature of the Leap or its audacious claims on behalf of the most marginalized people, students were curious to know more about the individuals behind the document and whether “it” was “going to happen.” “What do you mean by ‘it’?” I had occasion to ask again and again that summer. “Remember, guys, this is a manifesto; it’s a political vision, a piece of text.” But the questions persisted: “Do you think it will happen?” “How will we know?” “Who are these people?” “What are they doing now?”

As the summer came to an end, a core group continued to press me on the Leap. “Can we keep learning about this?” “Can we join?” Some were skeptical, but not in their usual dismissive ways. I remember Hassan, an often ill-mannered, irritated boy, insisting: “This is never going to happen. They won’t let it. None of the rich people are going to give money to poor people to fix their communities. Everything is just going to get worse.” As he pronounced this grave set of facts, Hassan looked at me, directly and with frightened eyes, and I could tell how desperately he wanted me to convince him otherwise. “What if you’re wrong, Hassan?”

September brought an end to our official interrogations of the Leap, a fact not entirely lamented by many of my high school students. Even those who had participated fully in collaborative activities all summer, who had worked in earnest to parse challenging readings and concepts, seemed pleased to see their familiar materials: the vocabulary paperback, the basal reader, the writing mechanics workbook. Still, for a particular set of students, 24 in all, I could tell that the Leap had ignited a curiosity, a hope, and in some cases an agitation that I felt compelled to sustain. Prior to leaving for late summer break, I reminded these students, whenever I saw them, of an idea I had floated a few times before, in different contexts: “What if we start a learning club,” I asked, “a kind of ‘think tank’ where we keep this summer’s analysis alive?” I was hoping we all might convene, even once — and perhaps try our hands at writing our own manifesto.

Joshua approached me immediately after the Labor Day break saying, “Can we meet to talk about Leap?” I was ready with a reply: “What if we organize a Leap chapter? An official teach-in event?” Joshua is a charismatic, bright, young man, capable of rousing his peers. And yet, I’ve known him to turn inward and disengage for long periods of time. Joshua was taken into Department of Children and Families custody as a child; he’s been in and out of state-detention facilities since he was 8 years old and is serving a long sentence for a very violent crime. Joshua seemed hesitant when I suggested the chapter, but he returned two days later with Cameron — a sweet, lanky 16-year-old, with large, bright eyes and a toothy, infectious smile. Cameron had always struggled in school and found the ideas of the Leap difficult to conceptualize. Even so, he is drawn to possibility and is innately hopeful, a fact that can surprise considering his background. Cameron grew up in extreme poverty; his educational file includes multiple accounts of teachers providing basic necessities, even food. As far as I know, Cameron has never had a visit since he became incarcerated two years ago.

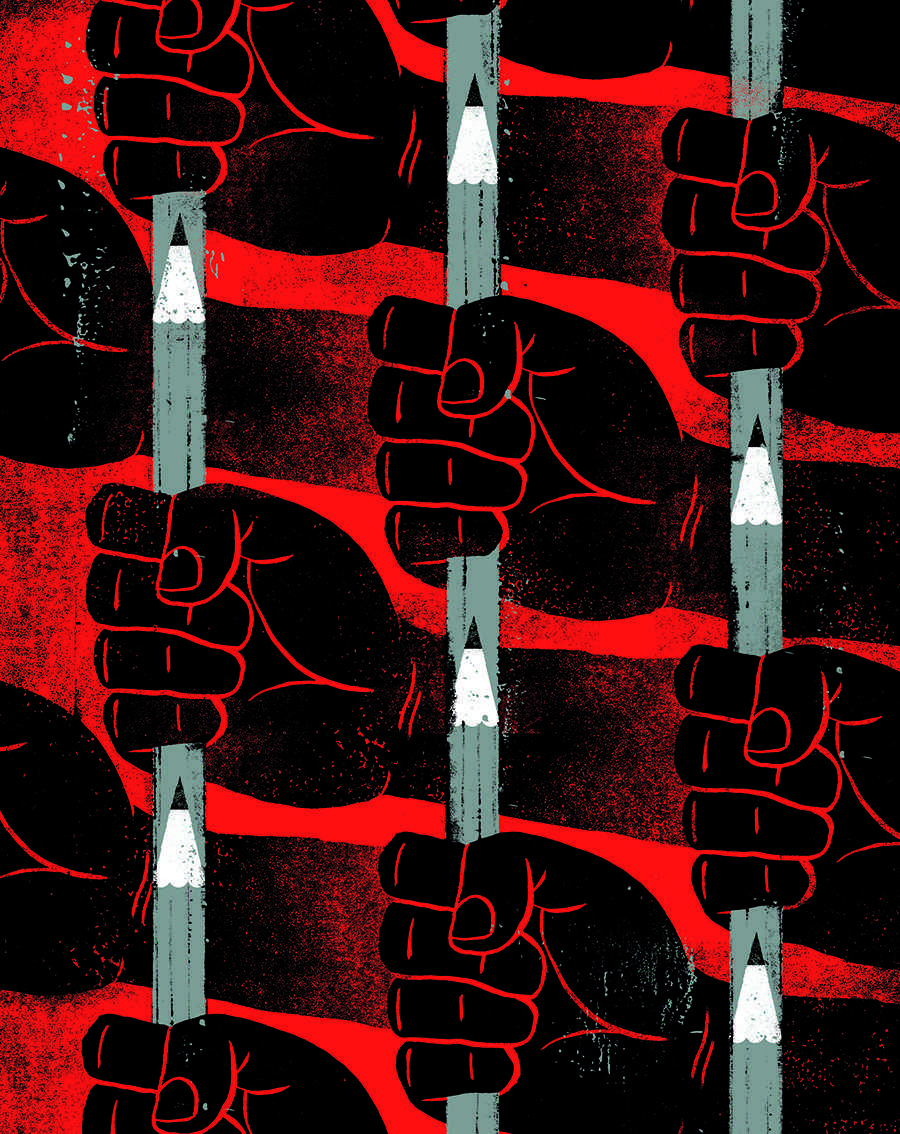

Cameron, Joshua, and 22 other students gathered in my room the first afternoon Leap-MYI met; Hassan was there too. We “circled up”; using an Expo marker as a talking piece, students began sharing their ideas and hopes for the club: “Can we sign the document?” “Will you tell the Leap people we are doing this?” Several students in attendance that day were interested but also skeptical; I remember Dean — an exceptionally intelligent 18-year-old who rarely spoke up in class — saying, “These people are not going to care about us. Also there is nothing we can do in prison. We cannot be activists.” “What does that mean?” I asked. “What is an activist?” “It is a person doing things,” Dean explained, “making a difference, making changes. You cannot do that if you are in jail. You are not even really a person — like you’re property and we cannot even vote.”

The nature of activism was a theme we returned to throughout the year and an evolving concept as students did, in fact, find ways to “act” politically in the world — to write letters, sign petitions, advise the Leap team in Toronto. But, on that first day, what stands out in my mind is the excitement students felt at being “Leapers.” The identity transformed even kids like Hassan who I’d only ever known to be angry or apathetic.

I wanted Leap-MYI to be student-led, to develop from the curiosities of its learners — who I knew to have vastly different academic abilities. I also knew that meeting as a whole group would be difficult to arrange. Scheduling in prison is fixed by unalterable shifts and watches, and inmates have little time outside of regularly sanctioned activities. While I was, in the end, able to arrange a few formal gatherings of all Leapers (occasions where we signed the manifesto or listened to guest speakers), I wondered early on how we would maintain a sense of cohesion among the group. And so I asked students to think about what individual learning journeys grounded in the demands of the Leap might look like but also how we could remain connected as a club. Cameron had the idea of “portfolios”: “What if you gave us things to read — things we told you we wanted to know more about? We would need notebooks and folders. If you gave us a notebook and a pen, we could write you questions and you could write back answers. And we could tell you about more things we wanted to learn and you could provide more readings.” As it turned out, Leapers came in and out of my classroom regularly, on their way to other classes — to turn in, share, and discuss their portfolios. In this way, Leap-MYI was visible to other students. Sometimes I’d have Leapers, all enrolled in one class, circle up and spend time together — to have an impromptu “meeting,” where they could think through ideas together and plan events.

Cameron’s idea of the portfolios was immediately met with enthusiasm. Resources are scarce at Manson and inmates are allowed few items in prison. Generally, students are thrilled by specialty items — even office supplies — and so I sought and was granted permission to purchase each Leaper a brightly colored composition notebook and folder. Inside I placed a pen. And, as Cameron had suggested, Leapers began carrying these items back and forth to school and to monthly meetings. Their folders bulged with articles and essays; the notebook pages filled with questions and comments. These brightly colored portfolios became the symbol of our Leap community, as other students, correctional officers, teachers, and building administrators took notice.

In the notebooks, Leapers expressed curiosity about a term, idea, or movement they encountered in readings, in the manifesto, or in conversation with me or other Leapers: “What is restorative justice?” “What is a universal basic income?” “What is divestment?” “What is Black Lives Matter?” I responded by gathering items — articles, interviews, videos. I gave Leapers as much time as they needed to read and process new information. One by one, as they returned their notebooks — always with pages of queries and requests to know more — I would respond at length. Leapers regularly shared their notebooks with me and with each other, and I began to see a community of socially engaged, progressive thinkers taking shape.

It was important to me that students had chances to speak about their learning, to develop a critical vocabulary for expressing new-found political ideas and concerns. And so, I opened each of my regularly scheduled English classes by inviting any Leapers to share. Sometimes students were timid, but other times a Leaper would begin to instruct the rest of the class. I remember one exchange between Cameron and another classmate vividly: Cameron shared that he’d been reading about the Water Protectors at Standing Rock. “What is Standing Rock?” lots of students wanted to know.

Cameron’s explanation of the Indigenous movement was interrupted by a classmate not involved in Leap: “There are no Black people out there. Why are you learning about Indians?” Other students laughed; some grew distracted; private conversations quickly erupted. “Guys,” I said loudly, “what Leapers are discovering is that a lot of contemporary popular resistance is also helping to reveal the way different kinds of oppression are connected. The word is ‘intersectionality.'” I quickly reminded Cameron about an incredible series of meetings between Black activists and Standing Rock Sioux, at which the nature of solidarity was being debated in the light of certain historical truths.

He was then ready to counter, and he had their attention: “Oh yeah, I forgot. Did you know that some Indians owned slaves, and that some Black people are Native Americans, and that a long time ago these Black people were not given fair land rights on reservations?” His main interlocutor was not easily silenced: “That is what I am saying! Why should Black people help Indians? We don’t live out there.” But this time, Cameron had answers: “Did you know that runaway slaves and free Blacks joined the U.S. Army and killed Indians? They were called ‘Buffalo Soldiers.’ And did you know that Indians in Florida, when it was part of Spain, joined fugitive slaves in creating a safe place for slaves fleeing the United States?”

Moments like this were not rare; incidents where students, engaged in individual intellectual pursuit, seized on the chance to teach others. There was a certain palpable pride about being in Leap, one that could translate into the bold authority Cameron displayed in class. I thought of Cameron’s elementary school teachers, the ones who had brought him sandwiches and gave him paper to do assignments — “remedial tasks,” since he’d already fallen significantly behind. And I wished they could bear witness to Cameron’s self-confidence, his display of deep knowledge.

When we did meet as a whole group, I would work to return Leapers to a specific engagement with the manifesto. I remember one early meeting. In circle, we were discussing ideas behind a sentence we’d only glossed over the previous summer: “One thing is clear: Public scarcity in times of unprecedented private wealth is a manufactured crisis, designed to extinguish our dreams before they have a chance to be born.”

“What does this mean?” I asked the group. Hassan began, “They did this to us, man. They been keeping us poor.” I encouraged Hassan to speak in specific terms. “Who are they?” I asked.

Accusations began to fly, many over-simplifications and certain racialized and class-based assumptions. I tried another angle: “Who are you being called to identify with in the manifesto, by the term ‘our’? Whose experiences — of capitalist exploitation, for example — might be, at least in ways, like your own?”

Cameron stood at the front of the room, listing the categories that students called out: “the poor,” “Indigenous people,” “unpaid caregivers,” “immigrants,” “refugees,” “workers.”

“Where are we?” Hassan remarked, annoyed. “You see what I’m saying. We are not in the manifesto.”

Months later, when Leapers had the chance to take up this point with the Toronto team, no one was prouder than Hassan. Almost from the group’s inception, students worried that “the Leap people” (their term for the drafters) would not want a bunch of incarcerated kids connected with their document or mission. They felt sure that the ideas and issues of our learning community would not register as significant or valuable to the Leap organization.

Each time we met, these insecurities and laments would resurface — this despite the marked interest and deep commitment evident in individual portfolios. One afternoon, Hector interrupted Dean’s discussion of President Obama’s Clean Power Plan (a subject Dean had been reading about) with the charge, “We are not doing anything. We are just doing school, but we are not making a difference. Are we going to do anything real?”

Other students chimed in: “Does Leap know about us?” “What are they working on now?” “Is the Leap really going to stop climate change?”

It became increasingly apparent to me that I needed to foster a connection between the MYI-Leapers and the Leap Team in Toronto. Katie McKenna was my first contact; she was moved by the engagement of Manson’s incarcerated youth. With Katie’s help, all 24 Leapers became signatories of the manifesto and Leap-MYI was registered as a formal Leap Teach-In event. It is impossible to overstate what it meant to MYI Leapers to be embraced by the Leap team including Katie, Naomi Klein, Avi Lewis, Bianca Mugyenyi, and Jody Chan. All the way from Toronto, we received notes of encouragement, copies of Klein’s notable book This Changes Everything, a DVD of the resulting documentary, and a digital message inviting students to advise the team on how matters of incarceration might better be addressed in Leap’s vision.

We hardly knew what to expect the day I popped the DVD into a dusty television (or if the machine would even work!). But there they all were Ñ seated around a table, waving at us with emphatic “hellos” and warm smiles. After brief introductions (round-robin style), Naomi, Avi, Katie, Bianca, and Jody began answering our questions (ones I’d previously sent). They spoke plainly about the urgency for social justice climate action, and they appealed to the students for help. Students were amazed and moved by the desire these global actors showed for their unique knowledge and perspectives. I use the word “moved” literally. Viewing the digital message for the first time, Leapers were instantly active — laughing, back-slapping, calling out to the screen.

The correspondence that developed between the MYI-Leapers and the Toronto team was not the only connection Leapers made with the outside world. Over the course of the year, students participated in many activities that they recognized as “real activism.” When, in December, Shaun King launched the Injustice Boycott (a campaign against police brutality and other racist practices in New York, San Francisco, and Standing Rock), I told Leapers about it. They were eager to participate in many of its actions, including a letter writing campaign in support of New York’s 2017 Criminal Justice Reform Act. And they welcomed visitors including Dr. Johnny Williams, community organizer and professor of sociology at nearby Trinity College.

While I supported these efforts, what Leap-MYI confirmed, first and foremost in my mind, was the fact that critical pedagogy is a form of activism, as radical and transgressive as more overt forms of resistance — protest marches, letter writing, boycotts, and sit-ins. “We are not simply learning about activism,” I would remind students. “We are acting for social justice by developing the deeper knowledge that drives impactful change.”

Over time, I believe most of the Leapers understood this. Once I heard Joshua get teased for “always having his stupid Leap book.” “You’re not doing anything with all that,” his peer jeered. Joshua was not fazed: “I am doing something,” he said. “This is doing something.”

I’d like to end the story of Leap-MYI on a triumphant note with all 24 students circled up together, wholeheartedly engaged. But, sadly, I found the community difficult to sustain as the academic year wore on. Prisons are unpredictable places; most Leapers were transferred without warning. Many went to “segregation” for various violations and had their property, including their Leap materials, discarded. (This is typical with items not purchased on commissary.) Two lengthy lockdowns significantly impeded our momentum; I was forced to cancel more than one scheduled event. And some Leapers simply found their initial excitement waning. For these students, the transgressive elements that drew them to form a school club (the first of its kind at Manson) were eventually overcome by the difficulty of the academic work. As one Leaper put it, “I’m tired.”

From the start, it was important to me that “Leap-MYI” produce only feelings of cooperation, engagement, and success. And so in April, when I gathered remaining Leapers to help me plan a new summer session (this time on the exploration of political sanctuary), I spoke of Leap-MYI in the past tense. Regrettably, no one resisted. Still, the tone was celebratory and earnest; I asked Leapers to share what it meant to have become signatories of the manifesto and about their plans for an activist future. Looking over my notes of that day, Joshua’s response stands out: “I am part of an amazing group, a good group of people, saving the planet. It’s just a good feeling, Ms. Boccio. It is deep down good. I actually told my mom about it and everything.”

Rachel Boccio (rboccio@lagcc.cuny.edu) taught English and American literature at the John R. Manson Youth Institution in Cheshire, Connecticut, from 1998 to 2018. She is currently assistant professor of English at LaGuardia Community College in Long Island City, New York. The names used in this article have all been changed. Illustrator Adri Fruits’ work can be found at adriafruitos.com.

The 15 Demands of the Leap Manifesto

1. The leap must begin by respecting the inherent rights and title of the original caretakers of this land, starting by fully implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

2. The latest research shows we could get 100 percent of our electricity from renewable resources within two decades; by 2050 we could have a 100 percent clean economy. We demand that this shift begin now.

3. No new infrastructure projects that lock us into increased extraction decades into the future. The new iron law of energy development must be: if you wouldn’t want it in your backyard, then it doesn’t belong in anyone’s backyard.

4. The time for energy democracy has come: wherever possible, communities should collectively control new clean energy systems. Indigenous Peoples and others on the front lines of polluting industrial activity should be first to receive public support for their own clean energy projects.

5. We want a universal program to build and retrofit energy-efficient housing, ensuring that the lowest-income communities will benefit first.

6. We want high-speed rail powered by just renewables and affordable public transit to unite every community in this country — in place of more cars, pipelines, and exploding trains that endanger and divide us.

7. We want training and resources for workers in carbon-intensive jobs, ensuring they are fully able to participate in the clean energy economy.

8. We need to invest in our decaying public infrastructure so that it can withstand increasingly frequent extreme weather events.

9. We must develop a more localized and ecologically based agricultural system to reduce reliance on fossil fuels, absorb shocks in the global supply — and produce healthier and more affordable food for everyone.

10. We call for an end to all trade deals that interfere with our attempts to rebuild local economies, regulate corporations, and stop damaging extractive projects.

11. We demand immigration status and full protection for all workers. Canadians can begin to rebalance the scales of climate justice by welcoming refugees and migrants seeking safety and a better life.

12. We must expand those sectors that are already low-carbon: caregiving, teaching, social work, the arts, and public interest media. A national childcare program is long past due.

13. Since so much of the labor of caretaking — whether of people or the planet — is currently unpaid and often performed by women, we call for a vigorous debate about the introduction of a universal basic annual income.

14. We declare that “austerity” is a fossilized form of thinking that has become a threat to life on earth. The money we need to pay for this great transformation is available — we just need the right policies to release it. An end to fossil fuel subsidies. Financial transaction taxes. Increased resource royalties. Higher income taxes on corporations and wealthy people. A progressive carbon tax. Cuts to military spending.

15. We must work swiftly toward a system in which every vote counts and corporate money is removed from political campaigns.

_