Teaching Dance for Transformation

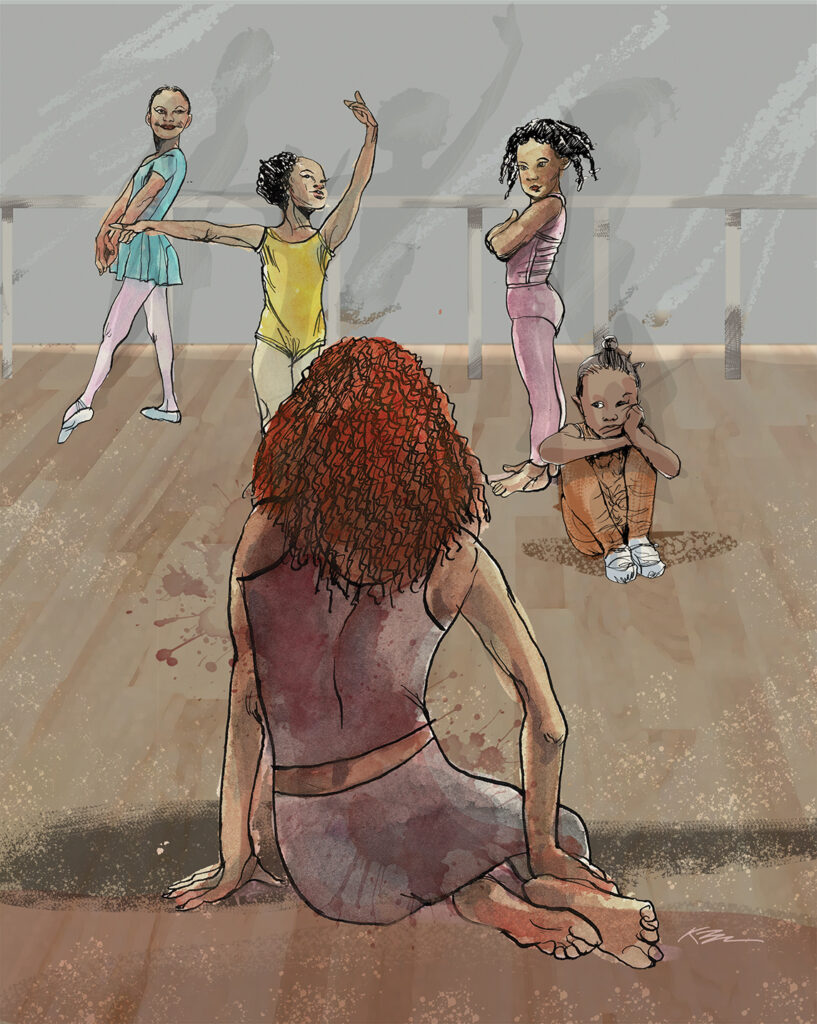

Illustrator: Keith Henry Brown

“5, 6, 7, 8!” “Do it again.” “Tuck in your tailbone. Point your feet!” “It has to be perfect.” “Again, again, again.”

When I first started as a dance teacher years ago, I found myself barking the same commands I heard in my own dance training. The words flowed from my mouth, bounced off the black Marley floor, and reverberated from the mirror-plastered walls. It felt natural — those words — like they had become a rhythm pulsing through my heart and into my pedagogy. The directives were what I knew and what I was used to.

My students at the time, mostly middle and high school-aged Black girls, met me in our community-based dance institute most nights of the week and Saturday mornings, where we honed the technical elements of dance and rehearsed choreography for shows and competitions. At the time, I vigorously demanded perfection from the dancers, as I grappled with tender wounds from years of trying to contort my body to fit a mold instructors and coaches insisted of me.

Historically, the culture of many dance spaces, particularly ballet, can be rigid. While we learn essential lessons about dedication and honing a craft, there are often subtle and not-so-subtle messages we hear that encourage us to police our bodies into unhealthy, false senses of “perfection.” A lot of my evolution as a dance teacher has been about unlearning those messages and control as a tool for discipline.

Donning black leotards, skin tone tights, and bare feet, students entered my classroom eager on some days and sluggish from long days at school on others. They also came to the dance classroom with questions, suggestions, fears, and triumphs. While a strict version of myself appeared in the midst of drilling choreography, I tried to maintain practices where I could make connections with students, such as greeting students as they came in the door. I’d offer a soft smile and in a sing-songy voice ask, “How was your day?”

“Ms. Cierra, school was rough today. I’m stressed. Can we meditate?” Ava offered.

“I’m frustrated because we don’t really learn any Black history at school. Can we look at Black dance history?” Lani asked.

“Can we use our dancing to make a change? I want to make a statement about the racism I’ve experienced using dance,” Desiree said.

I would nod my head and listen intently, brainstorming ways we could incorporate their ideas in class. In some instances, like Ava’s request for meditation, I’d shift the plan for the beginning of class and invite them to find a comfortable position while I led them through guided meditation.

I learned over time that these small touchpoints often yielded critical information. Students made important connections and thoughtfully examined their experiences. I learned that once I created space for them to share their wonderings, even within the short time period of a greeting, they began to vocalize what was on their minds. I collected their thoughts and feedback and worked with the director to designate time out of our rehearsals to explore and make space for the dancers’ needs. Every week, we carved out an hour to develop our own collective curriculum. I asked them questions like “What’s something you’d like to learn as a dancer? What topics are you curious about?” They’d eagerly shout out topics: “using dance for activism,” “self-care and taking care of our bodies,” “Black history,” “improv.” At the time, I didn’t realize how this effort would lead to a moment that would transform my pedagogy, and in turn, myself.

To be responsive to their ideas, I led an improv segment at the end of one rehearsal. I invited the dancers to spread out and be free in their bodies. “Make sure you have enough space. Close your eyes if that is safe and accessible to you. I’ll keep my eyes open and scan the room. Let whatever you feel in your body when the music flows through you happen.” I hit play on my lo-fi beats playlist as a smooth melody oozed out of the speaker. I watched as each dancer froze. There were no nervous giggles. Just sheer panic. I hadn’t created a space for them to experiment with liberation in their movement. I also hadn’t properly scaffolded improv as a skill. I threw my students into the deep end without presenting other opportunities for them to create rather than solely retain. While I made connections with students and asked them what they wanted to learn, the policing nature of my pedagogy stifled opportunities to be creative and explore their artistry. This policing pedagogy often manifested as me shouting commands during rehearsal, rather than engaging in reflection and conversation about how we could individually and collectively work on aspects of the choreography that would lead to our best performance.

I’ll never forget the distraught looks and wide eyes that met my gaze. A pit grew in my stomach. I felt my face get hot as the clock ticked to the hour mark, and it was time to release them to their next rehearsal. I felt stuck at that moment, like when you first jump into a pool and everything goes blurry and hushed.

I got in the car that night with tears uncontrollably visiting my weary eyes. I was furious that I hadn’t made the dance classroom a refuge for students to explore movement and imagine freedom as it might manifest in their limbs. The same policing I intensely protested in schools had made a home in my practice. I remembered my childhood self, who flinched every time a dance teacher told me I was doing something wrong or I couldn’t maneuver my body to look the same way as my peers. My experience in most dance classrooms was governed by hierarchy. The teacher offered critique and feedback, and we applied it. I learned to trust others with my body rather than to identify what my body felt like during particular movements. I began not to trust my body, often pushing myself beyond my limits. I knew I had to change my approach.

I was reminded of this pivotal moment of reflection after recently guest-teaching a dance class at a local high school. A friend invited me to teach a contemporary routine and facilitate a conversation about storytelling and expressing emotions through movement.

As I walked in, the dancers beamed grins at me. I scanned the space as one student ran up to me and wrapped her arms around my waist and exclaimed, “Ms. Cierra!” I taught her when she was younger, and then she took a break from dancing. I hadn’t seen her in years, but she was one of the first students I taught early in my career. Joy and memories flooded my body — an unexpected reunion!

The dancers were eager to learn and mostly energetic after a full school day. We spread out in the mirrored room with hardwood floors, and I led a gentle stretch to ease our bodies into an across-the-floor combination and short choreography. When it was time to go across the floor, I posed the question “What do you think of when you engage with contemporary dance?” A few shyly raised their hands. “Emotion.” “Flowy movement.” “Unstructured.” “A release.”

I prompted: “My invitation is to go across the floor with your own movement. Do what feels good to you. Show how you best express yourself. No one’s watching — this is just for you.” Nervous giggles filled the room. I turned on Khalid’s song “Better,” which melds hard-hitting background beats with a soothing tune. “Ooo, this is my song!” Chandra cheered as she closed her eyes and swayed back and forth. The dancers flowed across the floor, yet I could see some of them looking down, pausing, and even resorting to walking the remainder of the room’s length after only a few steps. I watched as some dancers allowed themselves to move freely for the first few beats and then shifted into shrugged shoulders and timid movements that communicated uncertainty.

After they all went, I praised them. “That was beautiful. I could see you putting yourself outside of your comfort zone. That’s so important in dance and in life.” Then, I offered an opportunity for reflection: “I noticed that some of you may have held back. I could see your body language change after a movement or two. I’d love to talk more about it. Would anyone feel comfortable sharing why?”

One dancer, Kayla, raised her hand, “I never really improv. A lot of what we do at school is always so structured, so there’s not much time for creativity or going outside the box.”

“Yeah! I mean, all day, we’re told ‘You can’t go to the bathroom,’ ‘Don’t talk unless I call on you.’ ‘Sit down.’ It’s like we’re not in control of our own bodies,” Jada stated.

“I’m just used to teachers giving the choreography or the lecture, whatever it is. Improv is different. It means we have the answers, not someone else,” Phoenix said.

Punitive logic is not just something that lies only within the police who patrol school hallways.

After teaching dance for more than a decade, I’ve seen this scenario many times. Improv is uncomfortable for many of the dance students I’ve worked with partly because when probed further, students describe how the process of schooling controls them. They have to stand in a straight line in the hall, go to the bathroom only at certain times, and are asked to regurgitate facts for good grades to be deemed “successful” by a rigid standard. The factory model of schooling persists, where educators require students to comply with directions rather than engage in thoughtful critique not only of the world around them but also of the structure of schooling in which they spend their days. When we direct them to vocalize their ideas and emotions only when it is most convenient for the teacher, students learn to mistrust their physical needs and in turn, themselves. This permeates into the dance classroom.

Punitive logic is not just something that lies only within the police who patrol school hallways. Rather, police is a verb — something we must work to disrupt and dismantle in our practices and our pedagogy. While my original orientation was to dictate commands — remnants of what and how I’d been taught — I learned that I didn’t have to perpetuate those practices. I could create a new culture and adopt a new approach. As abolitionist organizer Mariame Kaba states, “When we set out trying to transform society, we must remember that we ourselves will also need to transform.” I don’t always get it right, and I’ve also had to learn that I have to extend grace to and not police myself in the process.

There is great power in teaching and modeling discipline and learning how to hold ourselves lovingly accountable that doesn’t rely on control and punishment. For instance, in dance, we do this by training, showing up to class, observing strengths and working to improve growth areas, taking care of ourselves, learning choreography, asking questions about the movement to get to clarity, pouring emotions into the storyline of a piece, and supporting fellow dancers. This doesn’t have to be punitive, where we penalize students for doing a step incorrectly or missing a count. Rather, we can ask questions to lead students to understand who they are as artists, and in turn, humans in this world. For instance, I now find myself encouraging students to reflect “What did that movement feel like in your body? What would help you more fully express that movement? If you did that movement again, what would you like to do the same or differently? What does this piece mean to you? What story are you trying to tell and what character are you portraying in this piece?”

It can be freeing to use classrooms as space for wonder, imagining, and critique. We can provide spaces for students to practice freedom, to find joy and beauty in movement — to express the kind of people they want to be, in the world they want to live in. And, in the words of Robin D. G. Kelley, like a revolution, liberatory pedagogy is a “process that can and must transform us.”