Taking Multicultural, Anti-Racist Education Seriously

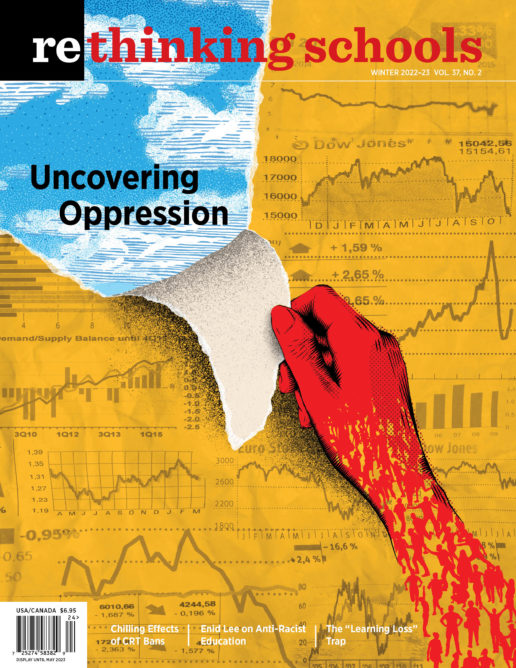

We are in the midst of a right-wing assault on anti-racist education. The cynicism reflected in statements from legislators, conservative activists, and Fox News pundits is breathtaking. As the authors of “The Chilling Effects of So-Called Critical Race Theory Bans” demonstrate in this issue (see p. 18), the measures are intended to stifle any classroom discussions of racial justice. At last count, 36 states have passed or are considering 137 bills to restrict teaching about racism or LGBTQIA issues. And the RAND Corporation reports that almost a quarter of school administrators in the country have warned teachers to stay away from social/political issues.

We thought that now would be a good time to revisit one of the most-read articles Rethinking Schools has published: then-managing editor Barbara Miner’s 1991 interview with the renowned anti-racist educator Enid Lee. It was one of our earliest statements on what anti-racist education is — and is not. Following the original 1991 interview, Lee responds to some questions about the context of anti-racist education today.

—Rethinking Schools editors

What do you mean by a multicultural education?

The term “multicultural education” has a lot of different meanings. The term I use most often is “anti-racist education.”

Multicultural or anti-racist education is fundamentally a perspective. It’s a point of view that cuts across all subject areas, and addresses the histories and experiences of people who have been left out of the curriculum. Its purpose is to help us deal equitably with all the cultural and racial differences that you find in the human family. It’s also a perspective that allows us to get at explanations for why things are the way they are in terms of power relationships, in terms of equality issues.

So when I say multicultural or anti-racist education, I am talking about equipping students, parents, and teachers with the tools needed to combat racism and ethnic discrimination, and to find ways to build a society that includes all people on an equal footing.

It also has to do with how the school is run in terms of who gets to be involved with decisions. It has to do with parents and how their voices are heard or not heard. It has to do with who gets hired in the school.

If you don’t take multicultural education or anti-racist education seriously, you are actually promoting a monocultural or racist education. There is no neutral ground on this issue.

Why do you use the term “anti-racist education” instead of “multicultural education”?

Partly because, in Canada, multicultural education often has come to mean something that is quite superficial: the dances, the dress, the dialect, the dinners. And it does so without focusing on what those expressions of culture mean: the values, the power relationships that shape the culture.

I also use the term anti-racist education because a lot of multicultural education hasn’t looked at discrimination. It has the view “People are different and isn’t that nice,” as opposed to looking at how some people’s differences are looked upon as deficits and disadvantages. In anti-racist education, we attempt to look at — and change — those things in school and society that prevent some differences from being valued.

Oftentimes, whatever is white is treated as normal. So when teachers choose literature that they say will deal with a universal theme or story, like childhood, all the people in the stories are of European origin; it’s basically white culture and civilization. That culture is different from others, but it doesn’t get named as different. It gets named as normal.

Anti-racist education helps us move that European perspective over to the side to make room for other cultural perspectives that must be included.

What are some ways your perspective might manifest itself in a kindergarten classroom, for example?

It might manifest itself in something as basic as the kinds of toys and games that you select. If all the toys and games reflect the dominant culture and race and language, then that’s what I call a monocultural classroom even if you have kids of different backgrounds in the class.

I have met some teachers who think that just because they have kids from different races and backgrounds, they have a multicultural classroom. Bodies of kids are not enough.

It also gets into issues such as what kind of pictures are up on the wall? What kinds of festivals are celebrated?

What are the rules and expectations in the classroom in terms of what kinds of language are acceptable? What kinds of interactions are encouraged? How are the kids grouped? These are just some of the concrete ways in which a multicultural perspective affects a classroom.

How does one implement a multicultural or anti-racist education?

It usually happens in stages. Because there’s a lot of resistance to change in schools, I don’t think it’s reasonable to expect to move straight from a monocultural school to a multiracial school.

First there is this surface stage in which people change a few expressions of culture in the school. They make welcome signs in several languages, and have a variety of foods and festivals. My problem is not that they start there. My concern is that they often stop there. Instead, what they have to do is move very quickly and steadily to transform the entire curriculum. For example, when we say classical music, whose classical music are we talking about? European? Japanese? And what items are on the tests? Whose culture do they reflect? Who is getting equal access to knowledge in the school? Whose perspective is heard, whose is ignored?

The second stage is transitional and involves creating units of study. Teachers might develop a unit on Native Americans, or Native Canadians, or people of African background. And they have a whole unit that they study from one period to the next. But it’s a separate unit and what remains intact is the main curriculum, the main menu. One of the ways to assess multicultural education in your school is to look at the school organization. Look at how much time you spend on which subjects. When you are in the second stage you usually have a two- or three-week unit on a group of people or an area that’s been omitted in the main curriculum.

You’re moving into the next stage of structural change when you have elements of that unit integrated into existing units. Ultimately, what is at the center of the curriculum gets changed in its prominence. For example, civilizations. Instead of talking just about Western civilization, you begin to draw on what we need to know about India, Africa, China. We also begin to ask different questions about why and what we are doing. Whose interest is it in that we study what we study? Why is it that certain kinds of knowledge get hidden? In mathematics, instead of studying statistics with sports and weather numbers, why not look at employment in light of ethnicity?

Then there is the social change stage, when the curriculum helps lead to changes outside of the school. We actually go out and change the nature of the community we live in. For example, kids might become involved in how the media portray people, and start a letter-writing campaign about news that is negatively biased. Kids begin to see this as a responsibility that they have to change the world.

I think about a group of elementary school kids who wrote to the manager of the store about the kinds of games and dolls that they had. That’s a long way from having some dinner and dances that represent an “exotic” form of life.

In essence, in anti-racist education we use knowledge to empower people and to change their lives.

Teachers have limited money to buy new materials. How can they begin to incorporate a multicultural education even if they don’t have a lot of money?

We do need money and it is a pattern to underfund anti-racist initiatives so that they fail. We must push for funding for new resources because some of the information we have is downright inaccurate. But if you have a perspective, which is really a set of questions that you ask about your life, and you have the kids ask, then you can begin to fill in the gaps.

Columbus is a good example. It turns the whole story on its head when you have the children try to find out what the people who were on this continent might have been thinking and doing and feeling when they were being “discovered,” tricked, robbed, and murdered. You might not have that information on hand, because that kind of knowledge is deliberately suppressed. But if nothing else happens, at least you shift your teaching, to recognize the native peoples as human beings, to look at things from their view.

There are other things you can do without new resources. You can include, in a sensitive way, children’s backgrounds and life experiences. One way is through interviews with parents and with community people, in which they can recount their own stories, especially their interactions with institutions like schools, hospitals, and employment agencies. These are things that often don’t get heard.

I’ve seen schools inviting grandparents who can tell stories about their own lives, and these stories get to be part of the curriculum later in the year. It allows excluded people, it allows humanity, back into the schools. One of the ways that discrimination works is that it treats some people’s experiences, lives, and points of view as though they don’t count, as though they are less valuable than other people’s.

I know we need to look at materials. But we can also take some of the existing curriculum and ask kids questions about what is missing, and whose interest is being served when things are written in the way they are. Both teachers and students must alter that material.

How can a teacher who knows little about multiculturalism be expected to teach multiculturally?

I think the teachers need to have the time and encouragement to do some reading, and to see the necessity to do so. A lot has been written about multiculturalism. It’s not like there’s no information. If you want to get specific, a good place to start is back issues of the Bulletin of the Council on Interracial Books for Children [published from 1966 to 1989 —eds.].

You also have to look around at what people of color are saying about their lives, and draw from those sources. You can’t truly teach this until you re-educate yourself from a multicultural perspective. But you can begin. It’s an ongoing process.

Most of all, you have to get in touch with the fact that your current education has a cultural bias, that it is an exclusionary, racist bias, and that it needs to be purged. A lot of times people say, “I just need to learn more about those other groups.” And I say, “No, you need to look at how the dominant culture and biases affect your view of non-dominant groups in society.” You don’t have to fill your head with little details about what other cultural groups eat and dance. You need to take a look at your culture, what your idea of normal is, and realize it is quite limited and is in fact just reflecting a particular experience. You have to realize that what you recognize as universal is, quite often, exclusionary. To be really universal, you must begin to learn what Africans, Asians, Latin Americans, the Aboriginal peoples and all silenced groups of Americans have had to say about the topic.

How can one teach multiculturally without making white children feel guilty or threatened?

Perhaps a sense of being threatened or feeling guilty will occur. But I think it is possible to have kids move beyond that.

First of all, recognize that there have always been white people who have fought against racism and social injustice. White children can proudly identify with these people and join in that tradition of fighting for social justice.

Second, it is in their interest to be opening their minds and finding out how things really are. Otherwise, they will constantly have an incomplete picture of the human family.

The other thing is, if we don’t make it clear that some people benefit from racism, then we are being dishonest. What we have to do is talk about how young people can use that from which they benefit to change the order of things so that more people will benefit.

I remember wondering if her sense of self was founded on

a sense of superiority.

I remember a teacher telling me last summer that after she listened to me on the issue of racism, she felt ashamed of who she was. And I remember wondering if her sense of self was founded on a sense of superiority. Because if that’s true, then she is going to feel shaken. But if her sense of self is founded on working with people of different colors to change things, then there is no need to feel guilt or shame.

What are some things to look for in choosing good literature and resources?

I encourage people to look for the voice of people who are frequently silenced, people we haven’t heard from: people of color, women, poor people, working-class people, people with disabilities, and gays and lesbians.

I also think that you look for materials that invite kids to seek explanations beyond the information that is before them, materials that give back to people the ideas they have developed, the music they have composed, and all those things that have been stolen from them and attributed to other folks. Jazz and rap music are two examples that come to mind.

I encourage teachers to select materials that reflect people who are trying and have tried to change things to bring dignity to their lives, for example Africans helping other Africans in the face of famine and war. This gives students a sense of empowerment and some strategies for making a difference in their lives. I encourage them to select materials that visually give a sense of the variety in the world.

Teachers also need to avoid materials that blame the victims of racism and other “isms.”

In particular, I encourage them to look for materials that are relevant. And relevance has two points: not only where you are, but also where you want to go. In all of this we need to ask what’s the purpose, what are we trying to teach, what are we trying to develop?

What can school districts do to further multicultural education?

Many teachers will not change curriculum if they have no administrative support. Sometimes, making these changes can be scary. You can have parents on your back and kids who can be resentful. You can be told you are making the curriculum too political.

What we are talking about here is pretty radical; multicultural education is about challenging the status quo and the basis of power. You need administrative support to do that.

In the final analysis, multicultural or anti-racist education is about allowing educators to do the things they have wanted to do in the name of their profession: to broaden the horizons of the young people they teach, to give them skills to change a world in which the color of a person’s skin defines their opportunities, where some human beings are treated as if they are just junior children.

Maybe teachers don’t have this big vision all the time. But I think those are the things that a democratic society is supposed to be about.

* * *

We first published this interview with you more than 30 years ago. What else should be emphasized all these years later about how we can take anti-racist education seriously?

We continue to take anti-racist education seriously when we renew our focus on two aspects of our work: standards and student voice. We must reclaim the curriculum standards, making sure to infuse the skills and processes that we expect students to understand with anti-racist content and approaches. In my earlier Rethinking Schools interview, I described anti-racist education as “a point of view that cuts across all subject areas, and addresses the histories and experiences of people who have been left out of the curriculum. . . . It’s also a perspective that allows us to get at explanations for why things are the way they are in terms of power relationships, in terms of equality issues.” To keep the anti-racist focus in this era of harassment, we must embed the elements of the missing and marginalized in our content. We should encourage students to find answers to the root causes and remedies to racial injustice — from the playground to the political arena — with questions like “Who else was part of this?” “What happened before this event?” “Who had the power to decide?”

The main thrust is to reclaim the standards, reclaim the work we are employed to do and ensure that all students feel included and acquire the skills and knowledge they need to function in the world and to change it so that they and others might experience greater justice and joy.

What is crucial is the application of anti-racist principles to students’ lives and the wider society. It’s what I call “making the mandated meaningful.”

In terms of student voice, let us make sure that we share and include in reports and conversations with families and district leaders, school board members, the press what students say they are learning — the empowerment they experience and the enlightenment they enjoy from the anti-racist curriculum. It seems as if the only student voices aired in the media are the ones of students who feel “uncomfortable” in the classroom. Where are the voices of the students of all racial backgrounds who are saying, “How come we did not learn about these things before?” “How can we make things better if we don’t find out what has gone on before?”

We can encourage students to share their feelings of discomfort within the context of the class. This does not have to wait until they get home. We need to recognize discriminatory language when it is used and repair harm. It’s not always a smooth journey, but one that teachers are undertaking with increasing courage, clarity, and compassion.

What you urge in the interview with Barbara Miner is under attack. Legislation outlawing what the right wing calls critical race theory has been introduced around the country. School board elections are being fought around issues of anti-racist curriculum. These efforts are having a chilling effect in schools, even where there are no new laws. How can educators respond to these attacks?

We must continue to organize across all kinds of identity and institutional differences. The accounts in Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change provide examples of this kind of organizing. The 8,000 teachers who signed the Zinn Education Project pledge to teach the truth about the history of racism and resistance to racism, despite the laws being passed against this, give us hope.

We encourage others to take a stand when we share the acts of resistance to racism that take place on a daily basis. These accounts of and engagement with struggle serve as the only springboard I have for carrying on with a sense of hope and urgency.