“Take These Nametags Off!”

Disrupting Poorly Designed Classroom Role Play

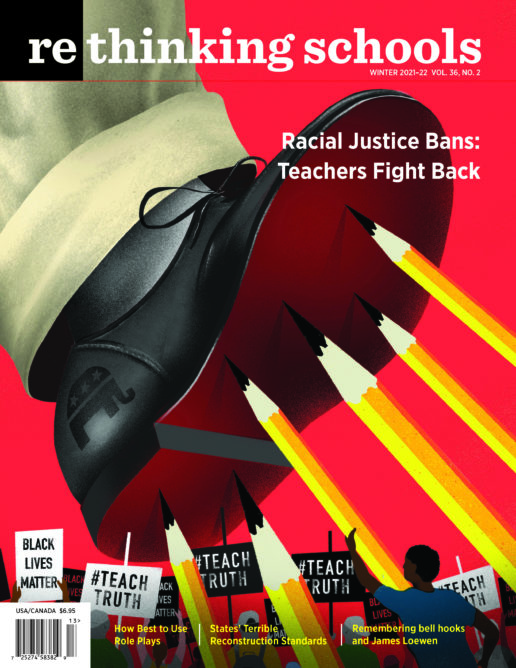

Illustrator: Adolfo Valle

Dear Class,

Our last session was terrible. We owe Azizah an apology for our unintended acts of racism. . . .

I remember staring at that letter for a long time but never reading beyond the first line. With my backpack still on, I sat in the chair like a reluctant tourist, wondering, “Why would he do this?” I used the warmth from the freshly xeroxed sheet of paper to offset the cold and increasingly awkward classroom. Hoping for nothing more but an end to this silent ambush, I suddenly heard crying. It wasn’t from me this time; it was from Holly, my classmate. She argued that she had no idea her actions were hurtful and how she could never be racist. She said she was sorry that she made me feel small. And like I’d learned to do much of my life, I nodded uncontrollably like a bobblehead. Again, Professor B just stood there.

I wish I could say I spoke with my head high that evening, but I didn’t. I wish I could say I later emailed Professor B about his senseless disregard for history and how he continued to ignore crucial teachable moments that would benefit our class of preservice teachers. But I chose to let it go. I wanted to tell him how uncomfortable his class was for me. Instead, I chose silence. Many years later, I am finally empowered to use my voice to disclose what I experienced as a Black undergraduate in a predominantly white space. Small moments like this became big and gave birth to my commitment to social justice teaching more than any course ever could.

Many years later, I am finally empowered to use my voice to disclose what I experienced as a Black undergraduate in a predominantly white space. Small moments like this became big and gave birth to my commitment to social justice teaching more than any course ever could.

It was junior year and just days after the hunt and murder of Trayvon Martin. I felt angry, sad, and alone with my thoughts and fears in school. I remember two different reactions from my undergraduate professors: 1. Business as usual. “Azizah, take your hood off inside, would yah?” 2. Hip-hop at the start of Professor B’s class.

I learned to anticipate his question: “You know this song, don’t you, Z?” With a forced smile, I responded “no” more often than “yes,” hoping he’d stop embarrassing me or at least play some reggae.

Professor B taught our elementary social studies methods course designed for multiple perspectives. He was a “culturally responsive educator,” he would say. He loved that term.

Professor B modeled greetings in different languages, including sign language. He encouraged us to incorporate students’ culture, like foods, language, flags, dances, and of course, music in our future classrooms. Students would feel they belong “like citizens,” he’d say. He pushed for us to have one-on-one conversations with students to foster genuine relationships with them and their families. I felt excitement early on and believed I could learn a lot from him. However, the more I listened to Professor B, the more I began to hear other things he wasn’t saying.

I took special note of his suggestion to “learn how to say difficult names correctly.” That struck me. What did he even mean by “difficult”? Did he find my name difficult? I found myself second-guessing whether or not I was hypersensitive to things he said. Was I trippin’? Before I knew it, his class felt like a chore, one I’d attend quietly with a masked smile. I wish I felt brave enough to ask him clarifying questions and to respectfully (or not) challenge things he said. However possible, I still found Professor B well-intended, yet on occasion uninformed, inappropriate, and offensive. Wasn’t he paid to know and do better?

One Wednesday, Professor B divided the class into two groups of about 10. He passed out task cards for a role playing activity, one he assured us we’d use one day. I was eager to participate, even grateful we’d finally be doing something interactive in class. Some of my classmates jumped up from their seats and clapped their hands. “I’m pumped,” one said. I was too, but like hearing an unexpected fire alarm, my heart jolted when I read the words on my label. It read “Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.” Great. Here we go.

My group’s task was to “pretend that Rosa Parks wasn’t really tired” and that she staged the incident to ignite the Civil Rights Movement. I had questions. Where is this coming from? Where are we going with this? Sure, I was excited to discuss a Black civil rights activist outside of the month of February, but I wondered why this and why now? First, anyone familiar with this history knew that Rosa Parks did not “stage” this incident, and had not sought arrest on Dec. 1, 1955. However, whether she had or had not intentionally plotted to disrupt racism wasn’t the point. The issue should have been institutionalized racism and not Rosa Parks’ intent or lack thereof. Knowing this, Professor B, and the great majority of my classmates, I knew for sure that this would be something else I’d have to vent about later.

“Put your nametags on! We’ll act it out in 10 minutes.” “It?” What was “it”? He offered no explanation or logic for why we were doing this activity. What were his teaching objectives? And, as prospective teachers, why wasn’t he sharing any of this with us? I had so many questions and although I wanted to, I couldn’t get my hand to raise or my mouth to move.

I looked around the room, searching for any sign that someone else heard the same unnerving alarm. Was I alone in seeing this task as nonsensical and problematic? Did anyone else at least think we needed a discussion, an explanation before breaking off cold into groups? Was anyone else concerned that this was going to be an absolute disaster? No one. I looked back to Professor B. Nothing.

The 10 of us stood in somewhat of a circle and began labeling our new selves. I read Rosa Parks, James F. Blake, and NAACP rep from my classmates’ chests before turning my head after a loud commotion. The noise came from the other group pretending that Rosa Parks was “both physically and emotionally tired” when she refused to give up her seat. They were laughing, jumping up and down some more, and having a good time attempting Southern accents. How? I thought.

Back in my group, two people weren’t assigned roles, so they volunteered to be bus wheels. “We got this. We’ll be the wheels, Professor.” Professor B nodded with a supportive smile from a few feet away.

Kneeling and rotating their arms in a circular motion, they sang, “The wheels on the bus go round and round, round and round, round and round . . .”

The wheels sang and laughed loudly. One wheel even rolled away. Everyone laughed, including Professor B, who looked on like a proud father. I couldn’t laugh. I couldn’t believe it. For 10 minutes, they gave one another ideas about how to make the role play more enjoyable. It became a competition between groups, like who could be the funnier “Rosa.” I stood there watching a scene from a horror film where the Black people died first. I could hardly breathe.

I found my pulse when Holly, the white woman playing Rosa Parks in my group, complained of joint pain as the reason she couldn’t give up her seat. “My knees gave out, driva. You gun have to help me up.” Fighting myself not to be the angry Black woman, I interrupted her and pulled the curtains down on the show. I remember the shock of my own tears and trying to fill the cracks between my words. “Stop!” I said something like “Please take these nametags off.” I went on to say that what had occurred was wrong, poorly designed, uncomfortably offensive, and racist.

I wasn’t trippin’. We had demonstrated a perfect example of how not to use role play in schools. For starters, the activity lacked purpose and truth. The professor had offered no explanation how this connected to the curriculum and what we were to get out of the activity. Had the objective been meaningful and appropriate, we should have had previous opportunities to establish ground rules and behavioral expectations for role play. His failure to engage us in a discussion about the aims of the activity, or to caution against fake accents and silliness invited stereotypes and outright disrespect. We became performers in a dangerous mockery of history. It couldn’t be undone, but it should never have happened.

Had he asked me, Professor B would have learned that I never wanted an apology. Instead, I needed him to lead a discussion on white privilege and to uninvite “white tears” to the conversation. I wanted space to say that Trayvon Martin, among many others, would be alive today if stereotypes didn’t matriculate into prejudices, discrimination, and acts of racism. And to my largely oblivious classmates, I wanted them to know that African Americans had been violently hosed down, shot, bitten by police dogs, and left for dead under bus wheels. Nothing was funny and I didn’t want any letter.

I needed us to unlearn the idea that saying “hola” and hanging flags from different countries magically made us culturally responsive teachers.

I needed us to unlearn the idea that saying “hola” and hanging flags from different countries magically made us culturally responsive teachers. (While at it, could we also unlearn the idea that Black music only meant hip-hop?) We all needed to learn the true nature of cultural responsiveness and to dive headfirst into anti-racist pedagogy. If there was ever a time, it was then. I needed Professor B to address the number of future teachers in the room eager to “save” children attending city schools. Teaching is much more than content knowledge, using colorful markers, and other pretty things. Students need teachers dedicated to humanity, consciousness, and truth.

My classmates and I also needed to relearn how to engage with one another, talk through what had happened, learn from it so we’d never repeat it. We desperately needed to relearn how to have fun as undergraduates and to hold one another accountable in that effort. We had no support in repairing the damage that was brought on by a senseless activity.

What we got instead was a “clean slate” that swept the entire episode under the “we are in this together” rug. I couldn’t tell you what the rest of the semester was like or whether I allowed myself to learn anything after that. I have no recollection of how Professor B ended class that evening or how long I sat there nodding my head, consoling Holly. I don’t know if I ever said anything to Professor B again. Although I was physically there, I never fully returned to that classroom. It is all a blur.

What remains clear is the lettering on my label that still reads Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. After I removed it from my chest, I placed it on the outside of my laptop, and although I have since purchased two new computers, I refuse to get rid of that one. It is my greatest reminder to find my strength and use my voice. It is my reminder that my silence (in fear of being seen as angry, problematic, and disruptive) has ended. Like my ancestors, my courage and strength are required for survival.

We must first remember to center our students’ humanity and to plan lessons and activities with each of them in mind. We also must plan for unexpected detours that generate difficult conversations, like those challenging the status quo. The discomfort will come, and should be welcomed, because it is a part of unlearning our socialized knowledge and recognizing oppressive practices in our world, our schools, one another, and ourselves. To do this, we must all commit to creating spaces that create true citizenship and belongingness where all students, especially those from historically marginalized groups, feel tall, seen, protected, and heard.

If you want to get more articles like this one — and to support independent journalism — subscribe now to Rethinking Schools magazine.