Sweet Stuff

Teaching About Sugar Subterfuge in Biology Class

Illustrator: Boris Séméniako

“Alright, everyone. Open up your backpacks and pull out any food or drinks you have.” In my high school biology classroom in Portland, Oregon, this set of directions left my students in a stunned silence, albeit a short one. Normally, I allow no food and drinks in our science classroom. The students quickly recovered and started rummaging through their bags to pull out chips, granola bars, candy bars, and an assortment of beverages.

I went around to each table and supplemented their collections with food packaging I had brought from home. “Did you eat all of this junk food by yourself?” a student teased. I responded that I had sacrificed for them and was eating potato chips for science.

Eventually, each group had a good assortment of food and drink containers with a mix of “healthy” and unhealthy items. I explained that we would be learning about a group of chemicals that build our cells and are found in our food. “As we learn about these biomolecules, we will also examine what we eat and the connection between our diet and health.”

Students then got to work, individually examining nutrition labels and other health claims on the packaging and writing observations in their lab notebooks, before sharing around the table. Following the small-group discussion at their tables, students had time to visit other groups to see if their observations held true with the nutrition information at other tables.

Students expressed surprise at the information they saw on the food packages. “I eat this kind of granola bar because I thought it was healthy because it is organic,” Ivan shared in one class, “but it actually has more sugar than the KitKat.” Another student compared yogurt containers and was amazed to see that one brand had 20 grams of sugar more than another brand. “How do they fit that much sugar in such a little container?” they asked.

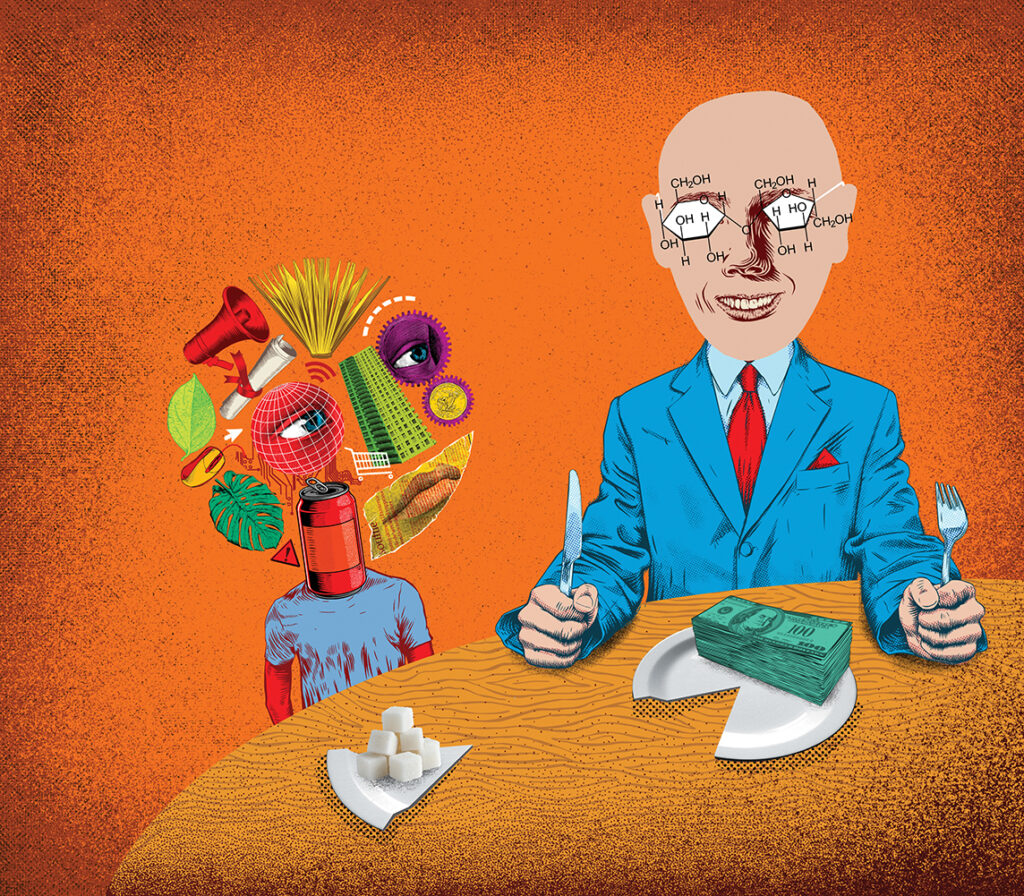

Over the last 40 years, there has been a rise in so-called “lifestyle diseases,” such as heart disease, high cholesterol, and type 2 diabetes. While we are consistently encouraged to just exercise more or eat less, many parts of our industrialized, for-profit food system actively encourage unhealthy food choices. Sugar is one culprit, hidden in our food at alarming rates. I wanted students to see not just the biology, but the subterfuge of this system.

People in the United States eat an average of 77 grams of sugar a day. Why do we eat so much sugar? Sure, it is delicious, but it is not just because we choose a sweet treat. Food manufacturers remove fat to make low-fat options and replace the fat with sugar. Sugar and salt are also popular ingredients to promote the shelf life or stability of processed food. Corporations hide sugar in foods we may not expect, such as ketchup, spaghetti sauce, and peanut butter. They also add it to foods in quantities we might not expect, such as in granola bars, yogurt, or cereal.

Food manufacturers have sought ways to produce food more cheaply. The use of high fructose corn syrup to heighten flavor is one common tactic. Among other things, the marketing of food has stressed value over health. Portion sizes in restaurants and stores have also grown, increasing our sugar consumption. When food health is discussed, the media mantra is “energy balance” and “calories in/calories out.” Coca-Cola is just one of many food and beverage manufacturers that lobby against restrictions on sugar. For example, grams of sugar are listed on nutrition labels, but not the percent daily value. (The American Heart Association advocates that adult women consume six teaspoons or 24 grams of sugar a day and nine teaspoons or 36 grams for men. A 12-ounce can of Coke has 39 grams of sugar.)

Perhaps none of these things seems that insidious at first. Food stability is food security. Cheaper food supposedly means less hunger. Exercise is good for us. But each of these things shifts responsibility to the consumer. In an effort to reduce production costs and increase profit margins, food and beverage manufacturers produce unhealthy food options. Our government is not regulating sugar. And it is literally killing us. A study published in early 2025 in the journal Nature Medicine found that sugary drinks alone result in 330,000 annual deaths throughout the world — from diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

The diseases that stem from unhealthy food disproportionately affect low-income families that have fewer food choices. Many of our students live in neighborhoods with few healthy food choices, with a lack of grocery stores or farmers markets.

During this six-week Sugar Subterfuge unit, students explored the daily food choices they make, in addition to learning about the biomolecules themselves. We examined the sneaky ways companies add sugars into our food and sugar’s connection with the rise of so-called “lifestyle” diseases. I wanted students to understand how hard it is to prevent sugar consumption and thus the onslaught of these diseases. At the end of the unit, we asked “Who is responsible for the rise of type 2 diabetes?” and put sugar — and those who push it — on trial.

“Diabetes Is Going Up”

After initial work to identify and define biomolecules, students completed a “K-W-L” chart about diabetes. I asked them to write what they knew about diabetes in the “K- Know” column, and anything they were curious about in the “W – Want to know” column. The open-ended prompt encouraged students to write personal stories, information, or facts.

Students knew there were several types of diabetes but wanted to know the differences. One group shared that sometimes you got diabetes because of the food you ate but wanted to know diabetes’ symptoms. Henry shared that his uncle died from diabetes when he was young and the class got extra quiet. Henry explained that he wasn’t particularly close to this uncle, but he wanted to understand more about what diabetes does to you over time and how you die from it. In a different class period, Elena shared that she was born with type 1 diabetes and has to closely monitor her blood sugar levels.

Following the student share-out, I presented a short introduction to diabetes, defining the disease, and explaining how the bodies and cells of those with diabetes work differently depending on which type they have. Then I projected infographics on the screen, and students discussed with their tables what they observed in each graph, as well as any inferences they could make.

The first graph showed diabetes diagnosis rates from 1980 until the present. “What do you see happening in this graph?” I asked.

“Diabetes is going up,” Ethan said. The next few graphs showed that 10 to 15 percent of diabetes cases are type 1, whereas 85 to 90 percent of cases are type 2.

The next slide also showed diabetes diagnosis rates and how they had increased, but by state and then by county. Students wondered why the southeastern United States has higher diabetes rates than where we are on the West Coast.

The last few charts grabbed their attention. One map was titled “Low-Income Households (more than one mile from a grocery).” I asked students what they noticed about how many grocery stores surround affluent neighborhoods in Portland, compared to less affluent neighborhoods. This was a topical issue in Portland. Students knew about a developer who began a building intending to house a grocery store in a low-income Portland neighborhood, but the grocery chain backed out at the last minute. The neighborhood still lacks a large grocery store. By contrast, our high school is situated near a relatively high-income area in Portland and students can walk to three different grocery stores. We discussed this disparity and the impact on someone’s ability to eat healthfully.

Sometimes presenting information like this makes me uncomfortable. Having a nuanced discussion about the role of race, income, and other demographics with teenagers is tricky. I do not want students to leave without seeing deeper connections between how marketing and the food industry prey on low-income communities, selling them the idea that cheaper is better. We circled back to their observations on the southeast United States and tried to tease out what else was at play. Marco stated that when they visit relatives in the South, they eat a lot of fried foods. Another student, Ben, agreed, but added, “Yeah, but there are also much higher poverty rates and terrible access to health care in many counties there.” Ultimately, the charts helped students see that people from low-income households nationally have higher rates of obesity and diabetes.

Why do people of color suffer from higher rates of type 2 diabetes? I wanted students to see that systemic racism limits access to healthy foods in neighborhoods. Decreased access to health insurance, safe housing, and quality education also occur. Each of these increases the risk of someone being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. The infographics we examine and discuss in this activity help us to see these connections.

Sweet Lab

I had one last lab I wanted to do with students before we put sugar on trial. Students now knew the four biomolecules were protein, carbohydrates, lipids, and nucleic acids. We had learned the molecular structures of these groups, as well as the types of foods we eat to attain these biomolecules. Now, it was time for the Sweet Lab.

I offered students a brief introduction to the biomechanics of our taste buds: Small receptors exist on our taste buds and as we eat sugar, the sugar molecules fit into those receptors to signal our brain that the sweet stuff is coming. Some molecules fit better than others into the receptor. In the Sweet Lab, students would taste different sugars and sweeteners to see if that sweetness signal varied. Students couldn’t believe their luck: “Wait, you’re telling me the lab is to eat sugar?”

Students tasted seven types of sugars and artificial sweeteners in a blind taste test. Some of the sugars included sucrose, starch, fructose, and maltose. The artificial sweeteners were aspartame and saccharin. As students tasted the samples, they ranked chemicals on a sweetness scale from one to 10. The first few rounds, they proclaimed sucrose and fructose “So sweet!” and made faces at the bland starch taste. Then the eruption of flavor responses really began when they tried the first artificial sweetener. “AAAAAA! Why did you make me eat that? It’s so bad!” students started to exclaim as they tasted the same sample size of the first artificial sweetener, Aspartame. Lab groups that were a little slower looked skeptical about whether they would try the sample, but bravery won out, and they shared the pain of something so sweet it hurts.

Following the taste test and ignoring their looks of indignation, I revealed what they had tasted. “Simple sugars fit well into these sweetness receptors, but artificial sweeteners have been engineered to fit even better. They fit so well into the taste bud receptors they send a super-sweet signal.” I asked students to think about what will happen in your body when your cells think sweet stuff is coming.

“I would start to get hyper!” Anna said. Other students laughed.

“Yeah, but you wouldn’t get any real energy from the artificial sweeteners,” Alex responded. “So you would just crash instead.”

I used that as an opportunity to reference our lesson on diabetes. “If your brain gets a signal that sugar is coming, what other responses will the body produce?”

Students shared out about insulin being produced by the pancreas.

“Exactly,” I said. “What if your body produces insulin, but there isn’t any glucose to enter the cells? This is what can further insulin resistance with the receptors on your cells, and some researchers think that, over time, this can lead to type 2 diabetes.”

Allies and Adversaries

Finally, it was time to introduce the unit’s final project and put Sugar on Trial. “Instead of a unit test, we will have a trial role play to examine blame for the rise in type 2 diabetes. Table groups will be assigned a role to research, and ultimately argue why ‘you’ are not to blame for this epidemic.” Before they learned their roles, however, I wanted them to get a sense of some of the arguments made by different players in this debate.

We watched the documentary Fed Up that postulates that the increase in obesity rates, incidences of type 2 diabetes, and other diseases are connected to the increase in sugar consumption, as soda and food manufacturers pumped more and more sugar into their products. The video includes accusations that students and parents were to blame for not eating healthier or exercising more, that food and beverage manufacturers should provide healthier options, and that our schools and government should set better rules and standards.

When the documentary finished, students discussed their reactions. “But when are we going to learn who we are in the trial?” Sydney asked with a sense of urgency.

After distributing the role cards, I handed out an initial survey that asked groups to describe who they were based on the role they were assigned and how they were impacted by the type 2 diabetes epidemic. The role cards had a paragraph of information defining who they were, with a synopsis of how the type 2 diabetes epidemic affected them, as well as a concern that other groups might have about them. The groups included Students, State Senators, Parents, Schools, Industrial Food Manufacturers, Coca-Cola, and the USDA.

Of course, I realize that groups like “Students” or “Schools” can be as diverse as all the students and schools in the country. I wanted to give students roles — “defendants” — that they could construct themselves, and that allowed them to defend themselves in whatever way made the most sense to them.

The following class, we did an activity called “Allies and Adversaries.” For each role, two students stayed at their table to give a short one-minute pitch about who they were and why they were not to blame for the rise in type 2 diabetes rates. Meanwhile, the other two members of the group rotated to other tables to collect information, writing notes about each group. At the end of the rotation, the original role group came back together to discuss which other groups might be allies and have a common cause, and which groups might be adversaries and could be vulnerable to attack in the trial. This is one of my favorite moments in the unit. At the start, presenters just get comfortable with their roles and by the final rotation they embody their role with complex backstories — some of which are included in their role sheets, some of which they invent.

The two groups that I had quick conversations with before this activity were the Parents and Students. Their role cards included information on how low-income individuals are especially affected by this issue. I wanted to make sure that as students took on these roles, they would honor and empower these groups, not play to stereotypes that could be demeaning. Although students could invent any backstory they wished, it needed to stay respectful; I didn’t want any caricatures. The students in these two groups agreed.

The “Allies and Adversaries” activity motivated students for the next class as well. In addition to completing internet research to find out more information about their own groups, they also wanted to dig up dirt on the other groups.

I reminded students that as we put Sugar on Trial, we would ask “Who is to blame for the rise in type 2 diabetes rates?” The trial would be organized into three phases. Each group makes an opening statement, a debate period ensues, followed by closing arguments. As we discussed the different tasks during the trial, I pointed out ways students could participate: read a prepared opening statement, prepare closing remarks, or be ready to participate in the debate portion.

Sugar on Trial

On the day of the trial, students quickly found their groups, talking in a nervous but excited way. Some intentionally talked loudly so that other groups could overhear them. “I can’t believe parents would serve such food to their children!” Sierra said in mock indignation. Students reviewed notecards, traded statistics with friends, and devised last-minute strategies. There was some light smack-talking, “The USDA is going down!” Even some desperate bargaining to make last-minute alliances: “Promise me you won’t accuse Coca-Cola! We just make soda!”

I was nervous. I had invited administrators, counselors, and other teachers to serve as guest judges. The trial began with opening statements. A student from each group read their prepared statement, introduced their group, and added statistics and information about why their group was not to blame for the rise in diabetes rates. When the debate began, it was furious and rarely lagged.

Different groups brought different strengths. In 6th period, the Coca-Cola group deflected all criticism that came their way and made convincing arguments against the Schools and Parents that served their products. Whereas in my 7th-period class, an optimistic “Student” group of activists schooled everyone about how the government and adults everywhere were failing them.

The following class we debriefed the activity. I asked students to complete a survey about the trial. It felt different to take the time to connect the science concepts directly to societal issues. Traditionally, a biochemistry unit will examine the macromolecules that build our diet. We would examine their chemical structure and determine how these chemicals build and operate our cells. I was curious what kids thought about our more social approach to the science.

“Diabetes is a prevalent problem in our country and is important to learn about so we can help prevent it and other health issues,” Jerred said. “It also shows how the food industry and government operate and helps me understand how our national health is at risk.”

“The unit connected what we were learning in biology to things like how the companies that make our food and drinks exploit their customers,” Coranna added. “I had never thought about topics like that in any of my other science classes before.”

* * *

Over the three years I taught this unit, my class sizes grew, and I added additional roles, including Novo Nordisk, a global medical research firm that produces 25 percent of the world’s insulin, but came under fire for raising its price.

Now, I ask students to read and respond to the article “Everything You Know About Obesity Is Wrong” by Michael Hobbes. Although obesity and diabetes are commonly linked, the two are not interchangeable or synonymous. The article effectively examines fat-shaming and demolishes the “get fat, get diabetes” equation. The article also emphasizes that “weight and health are not perfect synonyms” and that we must remember this in our discussions of topics, such as type 2 diabetes. In the future, I want to continue to improve this unit by adding more information about the health disparities that poverty creates. Another resource I now include is the video Unnatural Causes, which examines how the daily stress of dealing with racism is part of why we see increased health issues in communities of color.

My hope with this unit is to examine how our food systems impact our health, as well as to highlight what is wrong with placing the burden on the food consumer. Especially when we know this burden falls harder on people of color and people in poverty.

Students need to be aware of the sugar subterfuge in order to resist, but also to demand that others do their part.

For teaching materials related to this article, click below:

Who is to Blame for the Childhood Diabetes Epidemic? Trial Roles