Preview of Article:

“Stupid Book of Wrongness”

The Heartland Institute's Climate Change Denial Book Meets Informed 3rd and 4th Graders

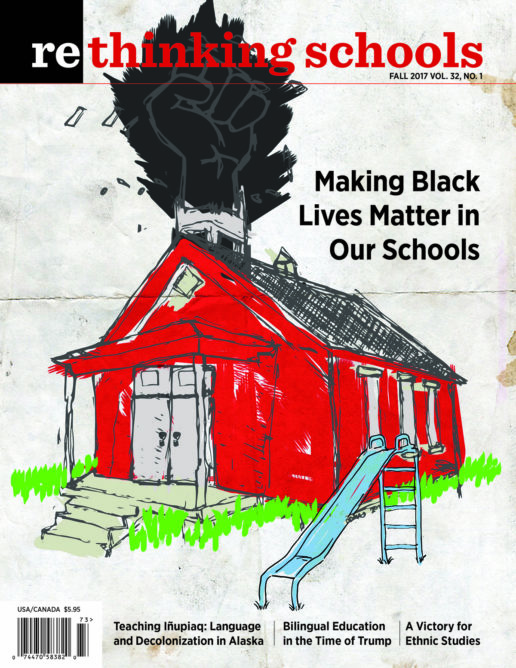

Illustrator: Nancy Zucker

I found Susan huddled in the corner making a new cover for the book. She had drawn cartoon flames leaping around angry faces, and as I peered over her shoulder she wrote enormous bubble letters across the top: “Stupid Book of Wrongness.” I looked at her quizzically. “Well,” she replied, “that’s how I feel about it!”

This moment was indicative of my students’ initial reaction to the book the Heartland Institute ostensibly sent to every science teacher in the country, Why Scientists Disagree About Global Warming. My students yelled, they cackled, and even as they “silently” read and annotated a Newsela article about the Heartland Institute’s campaign, they continually interrupted with loud objections.