Students “Warrior Up” for Climate Justice

Column: Earth, Justice, and Our Classrooms

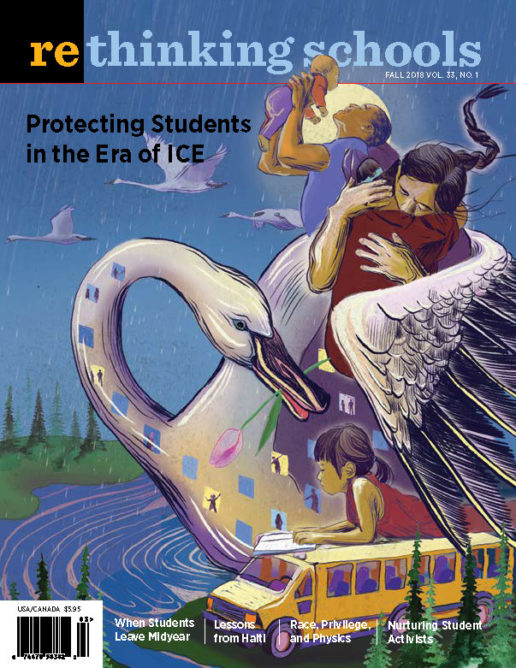

Illustrator: Rose High Bear

We’re sitting in the cozy, inviting library of Portland, Oregon’s Madison High School. For her research and presentation on a “climate warrior,” Ana chose the late Stephen Schneider, a leading scientist on the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. I ask what impact it had on her to study Schneider. She simply says, “He makes me want to be a better person.”

In an audacious embrace of Portland schools’ 2016 climate justice resolution, teachers in Madison’s Citizen Chemistry for All course — a class enrolling more than 300 sophomores in the school — adopted an essential question for the past two years: “Why are human changes to Earth’s carbon cycles at the heart of climate destabilization?” In a paper on Madison’s approach to studying climate change, “Warrioring Up for Climate Justice,” chemistry teacher Treothe Bullock and Restorative Justice coordinator Nyanga Uuka explained that teachers “wanted to support students in building a bridge between the personal and the planetary.” Students would demonstrate their learning in an annual two-day “Climate Justice Fair,” and would represent “communities which are engaging as ‘climate warriors,’ providing critical analysis of their work and/or proposing additional needed activism.”

An honest, rigorous look at the science of climate change can be terrifying and disheartening. Falling into cynicism is a hazard one confronts simply by living in our society, with its inequality, violence, and lack of democracy. But add to that, knowledge of the inexorable rise of greenhouse gases in our atmosphere — and what this heat-trapping pollution means for the Earth — and despair feels like more than a threat, it feels like common sense. Knowing this, Madison chemistry teachers focus not purely on the science of climate destabilization, but also on individuals and organizations taking action to reverse it, inviting students to research “climate warriors,” those who have not given up, those who “know the truth,” and yet are not defeated by it.

Madison chemistry teachers — which included Bullock and Rachel Stagner, both members of Portland schools’ Climate Justice Committee, and Tim Kniser — required students to identify one of the climate-related crises or issues explored in class and to create a slideshow, poster, short film, podcast, or some other way to “show how a ‘climate warrior’ is fighting against this issue.” And at the fair, students are expected to offer verbal and written feedback to at least four other presenters.

I attended the fair each of the last two years. In addition to other chemistry students, audience for the presentations includes other staff members, 9th-grade students, and community members.

At the inauguration of the first Climate Justice Fair in spring 2017, the library buzzed with anticipation. Bullock launched the day with an invitation: “There isn’t anyone who has the answer. We’re figuring it out.” Every student received a “Climate Justice Passport” to take notes in and had to identify the climate warrior, the issue they are involved in, the chemistry connection, and to evaluate the proposed solution.

Over the past two years, students’ “warriors” have been diverse and included: Xiuhtezcatl Martinez, a plaintiff in the landmark Our Children’s Trust lawsuit, Juliana v. United States of America; Nobel Peace Prize winner and former Irish president Mary Robinson, who works on the intersection of climate change and women’s issues; Rose High Bear (Deg Hit’an Dine), producer of the NPR series “Wisdom of the Elders”; West Virginia mountaintop removal activist Maria Gunnoe; Berta Cáceres, the Honduran Indigenous and peasant organizer who won the Goldman Environmental Prize in 2015 and was assassinated in 2016; Crystal Lameman, of Canada’s Beaver Lake Cree Nation, featured in the film This Changes Everything; and Zack Rago, a reef aquarist and scuba diver who appears in the film Chasing Coral.

The young woman presenting Rago as her “climate warrior” taught me more about coral during her short presentation than I’d ever known. (Did you know that coral is simultaneously rock, plant, and animal?) With a lovely smile, she admitted to having a crush on Rago.

In this year’s fair, one student presented on Robert Bullard, a scholar and activist often referred to as the father of environmental justice. One of the Latina students listening to the presentation said, “I’d never heard of environmental racism. I never really heard that this affects people of color more than others.”

Other students chose organizations or movements as their warriors rather than individuals. One student focused on 350.org, especially their “Keep it in the ground” campaign — “They really want you and me to get involved in this.” A couple students presented the Indigenous movement to oppose DAPL, the Dakota Access Pipeline. About the pipeline’s builders, Energy Transfer Partners, one student presenter commented: “There is not much depth to what they want. They just want more.” Another pair of students presented on the 350 Pacific Climate Warriors. One presenter, Julia, began intensely: “Before I get into it more, I just have to say that people’s homes are at risk. And how would we feel if we lost our homes?” After the short presentation, one student said, “I find it inspiring that they are working together to save their home. Their mantra is ‘We’re not drowning, we’re fighting.'”

One of the tensions in teaching about climate justice is that the more students come to recognize how dire the crisis is, the more they want to try to make a difference. And that’s great. But our culture is soaked in individualism, and inevitably, some students’ default reaction is to think only about what they can do individually. As I listened to presentations, I asked students what they intended to do with all that they’d learned from their “climate warriors.” One student said, “I intend to take five-minute showers from now on.” Another committed to drinking only from reusable water bottles. And one student, clearly moved by her research, described her personal commitment to abandon eating meat, because of cattle’s outsized carbon footprint.

There is nothing wrong with any of these. But we can’t consume — or conserve — our way to climate sanity. That’s going to take organizing and collective action. Encouragingly, a number of students emphasized this in their presentations. Leticia said that learning about the work of Indigenous activist Winona LaDuke, of Honor the Earth, “makes me want to protest pipelines.” Another girl, whose climate warrior was the Marshall Islands poet and activist Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner, said that Jetnil-Kijiner taught her: “Don’t ignore the issue. Talk to people. Participate in protests against coal mines and pipelines. And make changes in your own life.”

Despair is always a step away when we begin looking deeply at the contours of our climate emergency. But in Madison’s Climate Justice Warrior project, students encountered the hope and determination of activists alongside the disturbing science of climate change. And as dire as the news can appear, our curriculum needn’t be similarly grim. During both years of the Climate Justice Fair, the Madison library was electric with laughter — students telling stories, others listening respectfully, blurting out the frequent “wow” and “I never knew that.”

This is the kind of teaching that needs to be going on in every high school in the country.