Students Address Racial Justice at “Model Gary” Convention

High school senior Saleh Walton stepped before the audience of some 100 New Jersey middle and high school students and educators in the Seton Hall University auditorium on April 27, 2023. Ushering in the first day of the second annual “Model Gary” student convention, her words echoed through the hall, evoking approving grunts and snaps, before the crowd broke into applause.

. . . I’m still trying to figure out what we do to you.

You trade the chains for handcuffs,

then added bullets as if it wasn’t enough.

George Floyd was on tape.

Imagine all the lives taken in hush hush.

But I won’t say too much.

Ima say less.

And hopefully my words can make the monsters confess . . .

Walton’s spoken word performance addressing Black beauty, power, and oppression echoed many of the sentiments of the 1972 National Black Political Convention in Gary, Indiana, that inspired the “Model Gary.” The original convention, organized 51 years ago to “create unity but not uniformity” within the Black community, brought together an estimated 10,000 Black leaders from across the country, including Amiri Baraka, Charles Diggs Jr., Harry Belafonte, Rev. Jesse Jackson, Coretta Scott King, Betty Shabazz, and Bobby Seale. Much like today’s context, the original convention took place amidst widespread state violence targeting — and popular resistance led by — the Black community.

The Model Gary student convention began in 2022 as the brainchild of Dr. Kelly Harris, then-Director of Africana Studies at Seton Hall University and now the Senior Staff Director at University of Pennsylvania’s Africana Studies Department. Lead Model Gary organizer T.J. Whitaker, an English teacher at Columbia High School in Maplewood/South Orange, New Jersey, and a Zinn Education Project Prentiss Charney Fellow, explained that Dr. Harris’ vision for the Model Gary drew from the public school Model U.N. format and “infused the process with the politics” of the 1972 Black Political Convention in charting a unified path forward around issues impacting Black and other communities of color.

Teachers and students from schools in Newark and surrounding Essex County prepared for this year’s event for months in advance. Teacher-organizers began their work in November 2022 with weekly organizing meetings fueled by what Whitaker described as an “unwavering commitment to students/young people.” Later, high school seniors from the Martin Luther King Jr. Leadership Program at Seton Hall University joined the organizing team.

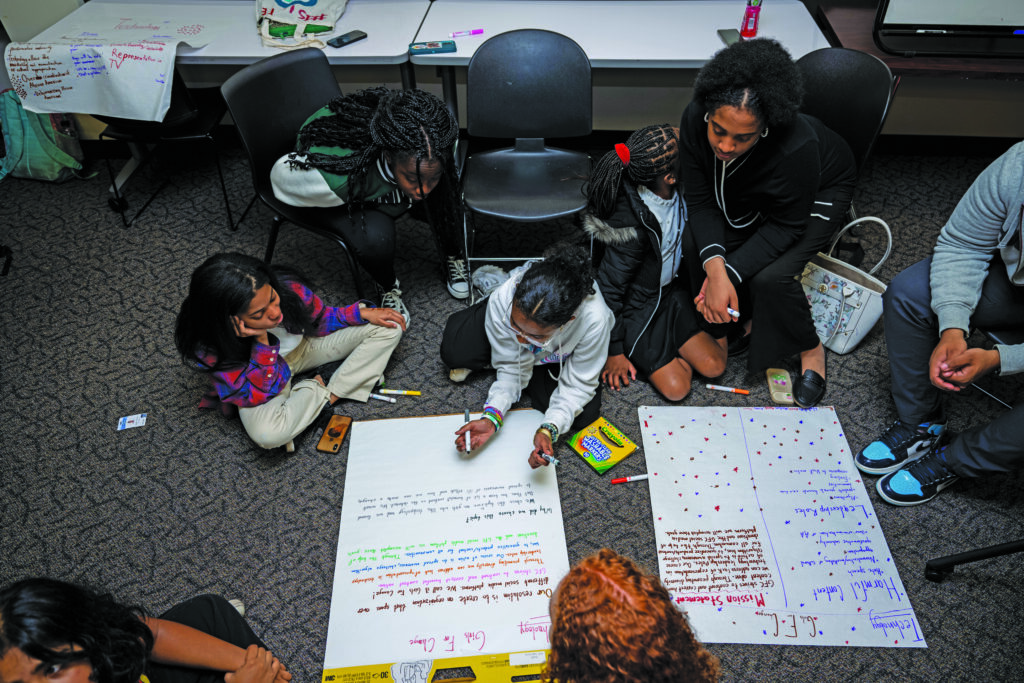

Student participants themselves worked for months writing position papers on problems they sought to address in BIPOC communities within the themes of education, politics, economics, BIPOC health, technology, arts/sports/entertainment, the prison industrial complex, and internationalism. These themes were selected by the convention’s steering committee based on those used in the first Model Gary convention and those suggested by students in their 2022 exit surveys.

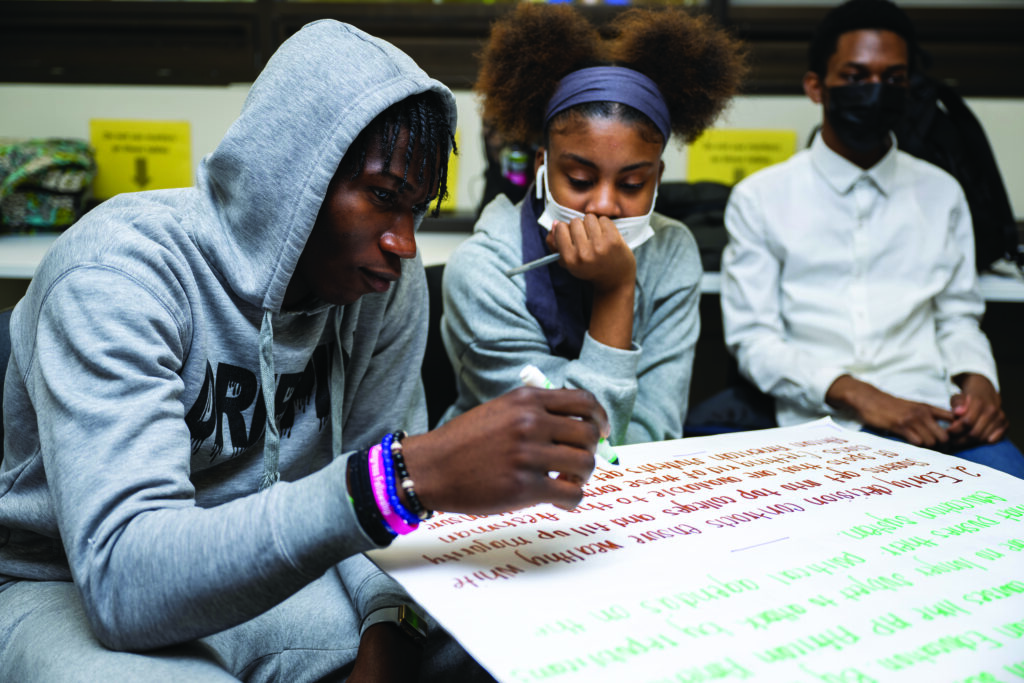

On the first day of the conference, after introductions, student participants gathered in groups, joining students from other schools who wrote position papers about the same theme, to discuss their ideas. Using their collective knowledge, students were instructed to formulate and come to a consensus on resolutions that would benefit BIPOC communities with the aim of presenting them at the end of the second day. Students showed a remarkable level of sophistication in their discussions, where facilitators — teachers and Seton Hall University Martin Luther King Jr. Scholars — largely stood back as students took the lead in crafting resolutions on their specific themes.

In one break-out room facilitated by Rodney Jackson, a teacher and convention organizer from Renaissance Middle School in Montclair, students discussed the nuances and challenges of seeking reparations. One participant suggested an incrementalist approach to “start by solving redlining, which can help solve gentrification, which could reduce the wealth gap. And then that could form connections to get a bit closer to possibly getting reparations.” Other students pushed back, with one urging that reparations should not be conflated with other measures addressing structural racism: “We shouldn’t be like ‘Oh, we’re going to fix redlining and gentrification . . . [and] that’s going to help us build up towards reparations. . . . Reparations is what we deserve after what we’ve been through. And [fixing] gentrification . . . and fixing redlining is just making sure that Black Americans get the bare minimum every other citizen gets.” These intense discussions continued into the morning of day two of the convention.

On the afternoon of the second and final day of the convention — after some six hours of discussion over two days — each group presented the resolutions they had reached before the entire convention body. These included:

- Reparations for Black Americans in the form of higher education and trade school funding, business and home loans, and federal funds to make K–12 school funding more equitable;

- The prohibition of laws that make teaching about race in schools more difficult;

- A renters’ bill of rights including more affordable housing, rent control, and eviction protections;

- Federal mental health recovery centers and programs that encourage BIPOC students to explore careers in health care;

- The creation of a grassroots “girls for change” social media group to combat racial/racist disinformation;

- The formation of a local youth program that teaches young people different skills and develops their hobbies to help them avoid gun violence;

- A number of measures to address the prison industrial complex beginning with the school-to-prison pipeline; and

- Extending the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policy that allows immigrants who arrived to the United States as children to achieve legal status.

Following Saleh Walton’s performance on day one, she described the Model Gary conference as “a beautiful opportunity to get to know other people and talk about the things that [school authorities] don’t want us to talk about.” She described how unsupported she felt by her own school administration following threats she received after mentioning Ralph Yarl during her school’s morning announcements. Yarl, a Black 16-year-old in Kansas City, Missouri, was shot in the head by a white homeowner after he went to the wrong address to pick up his younger brothers. “This [convention] right here is so necessary because we don’t have spaces where we are allowed to talk like this, where we’re allowed to have conversations like this. So please appreciate the space you’re in,” Saleh urged her fellow participants.

Other students agreed that the convention was a unique space where they could openly discuss issues relevant to their communities without the fear of reprisal or misunderstanding. “Here we can talk about whatever and no one is judged,” explained Chloé Guillaume, a second-year participant from South Orange Middle School.

Like the original 1972 convention, the Model Gary has emerged in a moment of political struggle — following the historic protests for racial justice spurred by the police murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and other Black Americans and amidst an economic crisis that impacts young people starkly. Whitaker, also a co-founder of MapSO Freedom School, an activist community education project, described that for him the Model Gary was “a way to go beyond the performative,” helping students, like those he saw leading community protests and school walkouts after George Floyd’s murder, to experience “the behind-the-scenes work” of becoming organizers and building a sustained student movement for racial justice.

The timing of the convention was also important according to Tracey Prince, a history and civics teacher at East Orange STEM Academy and convention organizer. “[T]his is what [the students] needed because they lost pieces of their childhood because of the pandemic,” she explained. “Therethere are so many social and political issues that happened during the pandemic that they had a front row to. Now we get to talk about it in a safe space.”

For student participants, the event has been a way to center the voices of the Black community and of young people. “I think it’s just great for an event to focus on Black issues, and it’s not just a subtopic,” said Hana El Shalabi, a 9th grader at Columbia High School and a second-year participant. According to student Kyree Robinson-Banks, the views of the younger generation are usually “thrown aside,” but the Model Gary allows students to “come up with our own ideas and our own solutions” to ongoing problems.

Larry Hamm, the youngest delegate to the 1972 convention, is now a seasoned activist and leader of New Jersey’s People’s Organization for Progress. In a closing address to this year’s Model Gary, Hamm reminisced about the beauty and power of the original convention. Looking out over the sea of engaged middle and high school students, he urged them to take political action: “Citizenship is being involved in civic life and bringing about outcomes that make life better for you, your community, the state, the nation, and the world. We need you. We need a new generation of activists. As Frantz Fanon said, ‘Each generation must realize its historical mission, fulfill it or betray.’ I hope that you fulfill that.”

Next year’s Model Gary will not just be a North Jersey event. In 2024, committed educators plan to bring the convention to a new audience, building a space for and with youth of color in Philadelphia.