Student Athletes Kneel to Level the Playing Field

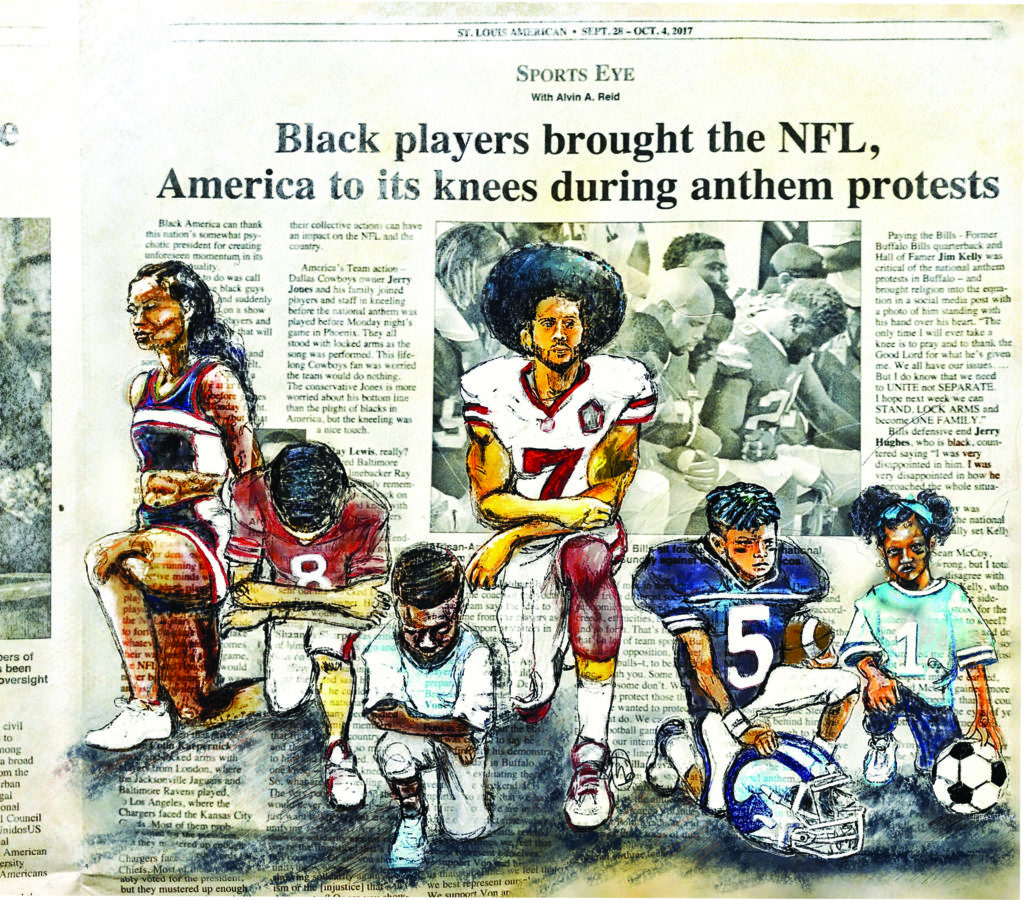

It started one Friday night in September 2016 with the jocks, the coaches, the marching band, and the cheerleaders. It was just two weeks after San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick took a knee during the national anthem before a game against San Diego, and the Black Student Union, the teachers, and the administration soon joined in too.

No one could remember the last time these disparate high school groups had come together in common cause at Garfield High School, the school I teach at in Seattle. But in times of great peril and great hope, barriers that may have once seemed concrete can collapse under a mighty solidarity.

The crisis of police terror in Black communities across the country is just such a peril, and the resistance to that terror, symbolized by athletes protesting — is just such a hope.

The power of athletes collectively joining the movement for Black lives first found expression on July 9, 2016, when the members of the WNBA’s Minnesota Lynx showed up at a game in warm-up shirts printed with the phrases “Black Lives Matter,” “Change Starts with Us,” and “Justice and Accountability,” along with the names of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, who had recently been killed by police. The movement spread quickly across the WNBA, with the New York Liberty, Indiana Fever, and Washington Mystics all refusing to answer reporters’ postgame questions unless they related to the Black Lives Matter movement or other social issues.

Then, in the initial weeks of the 2016 football season, as Kaepernick’s fledgling protest began to also take shape, critics bombarded him with insults and it was unclear what the response around the country would be.

And that’s when Garfield, and high schools and students around the nation, stepped up to the challenge.

On September 16, the entire Garfield football team, including the coaches, joined in the protest that Kaepernick set in motion by taking a knee during the national anthem. As Garfield football player Jelani Howard said, “It really affected people and showed that kids can actually make a difference in the world.” Head football coach Joey Thomas said of the action, “One thing we pride ourselves on is we have open and honest conversations about what is going on in this society. It led kids to talk about the social injustice they experience.”

The team’s bold action for justice made headlines. Their photo appeared in the October 2016 issue of Time that featured Kaepernick on the cover, and CBS News came to Garfield to do a special on the protest.

And the Garfield Bulldogs weren’t alone. A dozen high school football players in Sacramento also took a knee that same day. About 24 hours later the cheerleading squad at Howard University refused to stand, and a couple days after that several members of the Oakland School District Honor Band kneeled with their clarinets, trombones, tubas, and behind their cellos while playing the national anthem before an Oakland A’s game.

Kaepernick knew how important these youth protests were.

“We have a younger generation that sees these issues and want to be able to correct them,” Kaepernick told the Seattle Times about the Garfield Bulldogs taking a knee. “I think that’s amazing. I think it shows the strength, the character, and the courage of our youth. Ultimately, they’re going to be needed to help make this change.”

For the Garfield students, the protest was not only a move in solidarity with Kaepernick and against the ongoing crisis of state violence against Black people, it also served as a rejection of the rarely recited third verse of the “Star Spangled Banner,” which celebrates the killing of Black people. As the Garfield football team said in a joint statement:

We are asking for the community and our leaders to step forward to meet with us and engage in honest dialogue. It is our hope that out of these potentially uncomfortable conversations positive, impactful change will be created.

The conversation in the locker room led the team to analyze the ways racism is connected to other forms of oppression and the ways those forms of oppression disfigure many aspects of their lives, including the media and the school system. Yes, football players publicly challenging homophobia may be rare, but the Bulldog scholar-athletes wanted it known that it was time to upend all forms of oppression. Here was the team’s six-point program to confront injustice:

1. Equality for all regardless of race, gender, class, social standing, and/or sexual orientation — both in and out of the classroom as well as the community.

2. Increase of unity within the community. Changing the way the media portrays crime. White people are typically given justification while other minorities are seen as thugs.

3. Academic equality for students. Certain schools offer programs/tracks that are not available at all schools or to all students within that school. Better opportunities for students who don’t have parental or financial support are needed. For example, not everyone can afford Advanced Placement (AP) testing fees and those who are unable to pay those fees are often not encouraged to enroll in those programs. In addition, the academic investment doesn’t always stay within the community.

4. [Opposition to] Lack of adequate training for teachers to interact effectively with all students. Example, “Why is my passion mistaken for aggression?” “Why when I get an A on a test does the teacher tell me, ‘Wow, I didn’t know you could pull that off’?”

5. [Opposition to] Segregation through classism.

6. Getting others to see that institutional racism does exist in our community, city, state.

And the rebellion at Garfield didn’t stop with the Bulldogs’ football team.

The Garfield High School girls’ volleyball team all took a knee before a game that same week. At the following football game, the marching band and the cheerleaders joined the players on bended knee for justice. At the homecoming game — a space that is more associated with mascots and rivalry than with protest and solidarity — Black Student Union members lifted a sign during the national anthem proclaiming:

When we kneel you riot, but when we’re shot you’re quiet.

The sign referenced death threats directed at Kaepernick as well as cowardly wishes of harm made against the Garfield football team for their actions. One Black Student Union officer told me:

The anthem doesn’t represent what is currently happening in the U.S. and what has happened in the past — from slavery to police brutality and mass incarceration. Don’t be mad at us for protesting against these issues, be mad at the people who caused them.

Garfield’s protest was indicative of campuses around the country in the weeks after Kaepernick began his protest, and the movement burst onto the field of play nationwide. As Time magazine wrote:

Athletes across the country have taken a knee, locked arms, or raised a fist during the anthem. The movement has spread from NFL Sundays to college football Saturdays to the Friday night lights of high school games and even trickled down into the peewee ranks, where a youth team in Texas decided they, too, needed to take a stand by kneeling.

By the third week of the NFL season, the protests had been echoed everywhere from volleyball courts in West Virginia to football fields in Nebraska. Then on Sept. 15, the movement reached the international stage when Megan Rapinoe, an openly gay member of the U.S. women’s soccer team, kneeled for the anthem before a match against Thailand. “I thought a lot about it, read a lot about it, and just felt, “How can I not kneel too?” Rapinoe tells Time. “I know what it’s like to look at the flag and not have all your rights.”

There is a deep fear from the sports establishment (which often overlaps with the richest 1 percent of Americans) and from politicians of the potential of this protest. Team owners and school officials worry the protest will disrupt the branding of their sports and cut into the bottom line. The wealthiest 1 percent and the politicians who serve their interests have even deeper fears. The ability to reproduce a vastly unequal society, generation after generation, requires a populace that believes in the infallibility of the nation. These protests expose the great contradiction of a country that professes to be the freest on earth and yet has always brutalized Black people.

Institutional racism, from slavery, to segregation, to redlining, to our own era of mass incarceration, has played a seminal role in creating vast amounts of wealth for a mostly white owning class at the top of society. And yet far too often, the beneficiaries of this arrangement have gotten away with public declarations of living in the “world’s greatest democracy.”

Sports have long played a pivotal role in our nation as promoting blind patriotism and the myth of a meritocratic society. These protests threaten more than just the sensibilities of people who find the silent gestures distasteful. They threaten more than just the profit margins of some of the wealthiest corporations in the country. These protests hold the potential to expose the very deceit upon which oppression and exploitation rest.

So as with any movement to disrupt oppression and demand human rights, the reaction against it by those in power has been forceful and brutal. The U.S. Soccer Federation quickly changed its rules to mandate all players stand for the anthem. Youth across the country have been reprimanded and even kicked off teams for protesting. And Colin Kaepernick has lost his job.

For the 2017 NFL season, Kaepernick has been shut out of the league, with the owners actively refusing to sign him to any team, even as a backup quarterback. Owners may have been hoping that with the example of Kaepernick losing his job over the protest that it would intimidate others from taking up the cause. But despite the attack on Kaepernick, players such as Seattle Seahawk Michael Bennett, San Francisco 49er Eric Reed, and Philadelphia Eagle Malcolm Jenkins continued to protest during the anthem. Even several white NFL players, such as Chris Long and Justin Britt, took to standing next to these protesting athletes with a hand on their shoulder in solidarity.

Then before week three of the 2017 NFL season, President Donald Trump used a speech in Huntsville, Alabama, to attack players who protest during the national anthem. Trump said, “Wouldn’t you love to see one of these NFL owners, when somebody disrespects our flag, to say ‘Get that son of a bitch off the field right now, out. He’s fired. He’s fired!'”

Trump had hoped these words would lead to the disciplining of any player who had the audacity to exercise free speech. But instead, his words were a lit match to the tinderbox of rebellion that swept across the league. Some 200 players protested that week. Almost the entire Oakland Raiders team sat or kneeled for the anthem. The entire Seattle Seahawks and Tennessee Titans teams refused to come out of the locker room during the national anthem, with the Seahawks releasing a statement saying:

As a team, we have decided we will not participate in the national anthem. We will not stand for the injustice that has plagued people of color in this country. Out of love for our country and in honor of the sacrifices made on our behalf, we unite to oppose those that would deny our most basic freedoms. We remain committed in continuing to work towards equality and justice for all.

And in the wake of Trump’s comments and the horrible reaction by NFL team owners, student athletes around the country have continued to rise up for Black lives as well.

Members of the Traip Academy girls soccer team in Kittery, Maine, kneeled in protest during the anthem. So did high school football players on both teams at a game in Evanston, Illinois. And a few hundred students at an Alameda, California, high school took a knee after classes on the Monday following the weekend of NFL controversy, as proposed by the high school’s student body president — a move no doubt inspired by the student athletes who protested during the anthem the previous year.

Increasingly, threats are being made — and even carried out — against those who engage in these protests.

On September 28, 2017, Waylon Bates, the principal of the public Parkway High School in Bossier City, Louisiana, said the school “requires student athletes to stand in a respectful manner throughout the national anthem during any sporting event in which their team is participating. . . . Failure to comply will result in loss of playing time and/or participation as directed by the head coach and principal.”

In Cahokia, Illinois, youth football coach Orlando “Doc” Gooden was suspended from coaching after his team of 7- and 8-year-olds took a knee during their September 17, 2017, game in response to the acquittal of St. Louis cop Jason Stockley for the killing of Anthony Lamar Smith.

And in Houston, Cedric Ingram-Lewis and his cousin Larry McCullough were both kicked off their high school football team because of their protest during the anthem at a game on September 29, 2017. “We had to get our message across: End racial injustice and the oppression of Black people,” Ingram-Lewis told the New York Times.

While the threats and intimidation have been real, the protests continue because the oppression that caused the protests hasn’t ceased. And while the professional players and student athletes are not on the same field, they are side by side in the struggle.

If Colin Kaepernick had been the only one to kneel in protest of police brutality during the anthem, it would have been an important act of moral courage. But when young athletes around the nation found the same bravery, it helped launch a mass movement of athletes at every level of sports in what has become one of the leading edges of the movement for Black lives. There can be no doubt that this movement is having an impact when you consider an October 2, 2017, USA Today poll that found 68 percent of respondents believe Trump’s call for NFL owners to fire the players and fans to boycott their games was inappropriate.

When the story of the Civil Rights Movement is told, too often the many great leaders of the movement obscure the hundreds of middle and high school students who protested and filled the jails in opposition to legal segregation. But let us not forget that it was the mass mobilization of youth in cities like Birmingham, Alabama, that played a pivotal role in breaking the back of Jim Crow.

And let us not forget to tell the story of our youth today who, at great personal risk, are fighting to level the playing field by taking a knee in the struggle for Black lives.

Jesse Hagopian teaches ethnic studies at Seattle’s Garfield High School, is a member of the Social Equity Educators (SEE), and is an editor of Rethinking Schools. You can follow him on Twitter @JessedHagopian. A previous version of this article was published by The Progressive in October 2016.