Standing with Standing Rock

A role play on the Dakota Access Pipeline

Illustrator: Dark Sevier/Flickr Creative Commons

Like many teachers, I use my summers to fill gaps in my knowledge and curriculum. Last summer, I took a weeklong course with Colin Calloway on Native American history. He demanded two things of us: 1. that we not accept the inevitability of “what happened” and 2. that our historical analysis and curricula include Indian people as full participants in their own histories and in the history of the United States.

As Calloway writes, “American history without Indians is mythology—it never happened.” When I reflected honestly on my own U.S. history and government curriculum, I decided that on No. 1, I was doing a passable job. But on No. 2, I was a failure. So, as I looked to the year ahead, I promised myself to hold true to Calloway’s non-negotiables for approaching Native history.

At the same time, my social media feeds began to blow up with references to a protest of Indigenous peoples in North Dakota. The more I read and learned about the Standing Rock resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), the more obvious it became that this story must make its way into my curriculum. Here was a fascinating and important story—a story that literally cannot be told without recognizing Native peoples as full participants in their own, and U.S., history.

The resistance at Standing Rock began in April 2016 with the founding of the Sacred Stone Camp near the confluence of the Missouri and Cannonball rivers. The Standing Rock Sioux say they were not adequately consulted during the permitting process for the construction of the $3.8 billion, 1,172-mile pipeline that crosses unceded treaty lands and multiple waterways. This “black snake,” as many in the movement refer to DAPL, would pump 450,000 barrels of crude oil per day under the Missouri River, just north of the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation. It threatens not just freshwater, but also sacred sites. Writing in The New York Times, David Archambault II, tribal chairman of the Standing Rock Sioux, put the pipeline into historical context:

It’s a familiar story in Indian Country. This is the third time that the Sioux Nation’s lands and resources have been taken without regard for tribal interests. The Sioux peoples signed treaties in 1851 and 1868. The government broke them before the ink was dry. When the Army Corps of Engineers dammed the Missouri River in 1958, it took our riverfront forests, fruit orchards, and most fertile farmland to create Lake Oahe. Now the Corps is taking our clean water and sacred places by approving this river crossing. Whether it’s gold from the Black Hills or hydropower from the Missouri or oil pipelines that threaten our ancestral inheritance, the tribes have always paid the price for America’s prosperity.

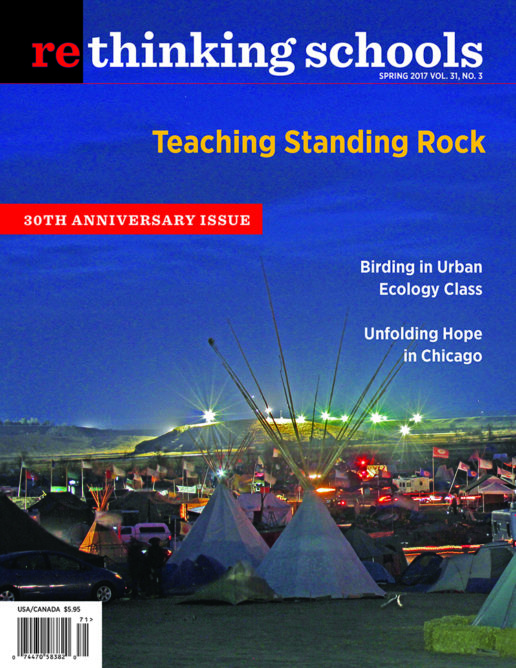

But if the expropriation of Sioux land is an old story, what may be a new story is the scope of Indigenous and non-Indigenous solidarity with the Standing Rock Sioux. More than 300 tribal nations have opposed the pipeline and pledged support to the tribe. Statements of solidarity have come from all corners of the globe. Social media lit up with #noDAPL campaigns that garnered millions of likes, clicks, signatures, and donations. By December, there were between 1,000 and 3,000 permanent camp residents. The number of Indigenous water protectors and allies on any one week averaged 6,000, swelling to as many as 10,000 on weekends. Soon there were camps within camps.

Aerial photos showed hundreds of tipis, tents, and vehicles arrayed under wide skies. Signs displayed now-familiar slogans like #noDAPL, Mni Wiconi (“water is life” in Lakota), Protect Our Water, and Defend the Sacred, and less familiar ones like: “I didn’t go to Alcatraz. I didn’t go to Wounded Knee. But before I die, I came to stand with the people.” In camp, visitors reported an inspiring set of communal institutions. As journalist Xian Chiang-Waren wrote for Grist,

Tidy donations tents are stocked with piles of warm clothing, blankets, women’s sanitary items, baby food, and firewood. There’s a daytime school for children to attend. When the state pulled water and port-a-potties from the camp, the tribe replaced them within an afternoon. Each day, hundreds of campers are fed for free.

Tribal leaders insisted on a simple but powerful mandate for the camps: peace and prayer. In a blog posted at the Greenpeace website, activist and organizer Peter Dakota Molof described his experience: “Every night we powwow—nations offering songs of thanks, resilience, and grief that we have to fight this pipeline at all. I wander back to my camp relatively early but the voices—the prayers—fill the night and begin early in the morning, greeting the sun as it rises.”

Bringing Standing Rock to Our Classrooms

As the movement at Standing Rock gained steam throughout the summer and fall, I set my curricular sights on Thanksgiving. Unveiling lessons on Standing Rock in November would be a powerful symbolic rejection of the lies about Indian people promulgated in our national Thanksgiving myths, in favor of a real story about real Indians. When I was joined in this work by my colleague Andrew Duden and Rethinking Schools curriculum editor Bill Bigelow, we quickly agreed that the story lent itself to a role play and got to work.

Andrew and I both teach a sophomore-level U.S. history and government class at Lake Oswego High School in Lake Oswego, Oregon, an affluent suburb of Portland. After spending the first quarter of the year on an election project, we began the second quarter with an investigation and critique of our textbook’s treatment of Columbus and Native peoples. For us, this was a natural place to insert a mini-unit on Standing Rock, even as our curriculum map indicated we should be in the midst of teaching about Colonial America and the American Revolution. Surely, we thought, students’ grasp of the themes of early U.S. history could only be deepened by learning about a modern example involving the rights of Indigenous people.

Before launching the role play, we wanted to give students a visceral and visual sense of the resistance under way along the Missouri River. We thought immediately of Amy Goodman’s wonderful coverage on Democracy Now!, specifically the horrifying footage of the use of dogs against water protectors by a private security firm. We also used “The Standing Rock Protests by the Numbers,” a short documentary posted at the Los Angeles Times.

We asked students to jot down questions that emerged as they watched. Afterward, they shared out their questions and it didn’t take long for them to name many of the fundamental issues at stake.

Greg asked, “Are the protestors angrier about the possibility of oil spills or that they’re building on burial grounds?”

Kaia asked, “What guarantee does the pipeline company have against the breaking or leaking of the pipe?”

Lindsey asked: “Is this pipeline really needed? What is it for? Can they move it somewhere else?”

Serena asked, “Who owns the land the pipeline is being built through?”

Cassie wondered, “Does the government care about what could happen to the water of these tribes?”

The DAPL Role Play

Our first and most important goal was to create a context for students to confront the complex social reality of DAPL, which includes the history and contemporary status of Indigenous rights, the power of the fossil fuel industry, the support for pipeline infrastructure from segments of organized labor, and the extent to which our government is protecting—or failing to protect—the land, water, and air. The role play asks students to explore these complicated dynamics as active participants. (See Resources for role play materials.)

The setting of the role play is a meeting, called by the president of the United States, to hear input on whether the pipeline should be completed. Students, representing five different groups, try to convince him that the project should be abandoned or allowed to proceed. Two of the groups are in direct conflict:

- Members of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe who are protesting the pipeline and are encamped along the Missouri River in North Dakota

- Energy Transfer Partners (ETP), the oil company building the pipeline

The other three groups provide additional context on the question of whether the pipeline should be built:

- Iowa farmers who have brought lawsuits and protested another section of the same pipeline

- Our Children’s Trust, a national organization of youth activists who are suing the federal government over its insufficient action on climate change

- North America’s Building Trades Unions (NABTU), a coalition of trade unions that supports the pipeline as a source of jobs

We assigned students to groups, handed out role sheets outlining each group’s beliefs and interests, and gave students some time to assume their roles.

We wanted students to do some writing before launching into the role play. Here is the prompt for an interior monologue:

To get more deeply inside your role, write a first-person narrative or poem from the perspective of your group about the building of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL). Draw on information from your role and your own imagination to build a persona so you can explore the feelings and motivations behind your beliefs. Make sure to include your position on the DAPL and why you see things the way you do. Are you hopeful? Are you fearful? What are your goals for the future?

Then we gave students a chance to share their writing with each other to help them develop their positions, hone their arguments, and build confidence for speaking as representatives of their group.

Before the role play’s main event, the meeting with the president, we asked students to travel around the room to meet with other groups. The goal was to learn new information (all the roles have different material) and to identify potential allies and opponents. In a class of 30, with groups of six, we asked three students to travel and three to stay “home” to meet with visitors from other groups. Students spent about five to seven minutes in each group, and then rotated to a new group. As students met with each other, they filled out a note-taking sheet.

We reminded students to speak in the first person and stay in character. As the meetings progressed, so did the energy level. The more comfortable students grew with speaking as representatives of their group, the more passionate they became in defending their positions. Conversations between the Standing Rock Sioux and ETP became particularly heated. Manju grabbed the attention of the whole room when, playing a member of the Standing Rock Sioux, he banged his fist on the desk and loudly proclaimed to a representative of ETP, “But we were here first, and it is our water that will be polluted when—not if—that pipeline breaks!”

Once students had gathered information from the other groups, they met back at home base to begin work on their presentations to the president. We asked each group to write a short opening statement that introduced themselves and their position on DAPL. We encouraged them to include persuasive facts and find ways to go beyond their narrow interests to appeal to the president, who is, after all, supposed to represent all the people of the nation. Because the role play took place after the election but before inauguration, students were quick to ask which president they should be addressing—the outgoing Obama or the incoming Trump.

“Why?” we asked, playing naive. “Would that make a difference in terms of what you put in your presentation?”

“Of course!” they replied. Although students had simplistic notions of each man’s interests (Obama pro-environment; Trump pro-business), their question—which president?—laid bare the fiction of our role play since, of course, presidents are never simply objective arbiters, giving equal time, consideration, and value to all interest groups.

As groups drafted their speeches, we walked around, listening in, reminding students to consider the arguments of other groups, and encouraging them to anticipate counter-arguments and to plan rebuttals.

With speeches written and practiced, the whole class circled up for the meeting with the president, played by a teacher. We opened the meeting: “I have brought you here today to help me better understand the situation now unfolding on the Missouri River in North Dakota. Ultimately, I am trying to decide whether or not to move forward with this project. I’d love to hear your input.”

We explained that students should carefully listen and take notes because they would have time after each speech to ask clarifying questions, state points of opposition or support, and provide additional, relevant information. If another group was mentioned in a speech they had an automatic right to reply. In addition, we often allowed other groups to chime in and offer a point. The result was a lot of heated conversation between and across groups.

Occasionally, as president, we interjected a follow-up question or tried to bait a group to make sure all dimensions of each group’s position got sufficient air time.

The ETP group kicked off the discussion. As expected, they painted a picture of a nation seeking to break free from its dependence on foreign oil, emphasized the safety of their project, and touted the benefits of economic development. Before they were even done with their speech, the hands of the Sioux group were high in the air:

“So how are we supposed to benefit?”

“This is our land you are taking away.”

“You can sit there and say the pipeline is safe, but it’s not your water that’s going to be polluted.”

The members of Our Children’s Trust also had grievances against ETP. Sarah was a particularly energized representative of this group. She found it outrageous that the company was ignoring the climate implications of the pipeline: “Oh. My. Gosh. Do you not understand that we are not going to survive if we do not take another route [than fossil fuels]?”

Cassie, also of Our Children’s Trust, undermined the safety arguments offered up by ETP: “Truck or pipeline, the oil is going to be burned. We’re the next generation. We need to think about that. This is the common good.”

When the debate moved to how quickly the economy might transition to renewable energy, Jacob, a member of the Standing Rock group, argued: “Wait a second. This is not just about climate change. This is about our land, which everyone seems to be ignoring.”

Maria, also with the Sioux, added: “Our rights are being taken away. You’re stealing our rights so you can benefit other people. That’s what’s happening here.”

The Iowa farmers also made arguments about rights and land. They emphasized the flawed and unfair use of eminent domain to seize their land for the pipeline.

The building trades union retorted: “But if this pipeline is abandoned, what happens to our jobs?”

Again and again, students were forced to consider the way statistics and language can be distorted. For example, ETP asserted they had received permits for the project. A permit certainly sounds official, but the Standing Rock representatives were quick to explain that not all permits are alike. Manju pointed out that ETP had used a Nationwide 12 permit, usually reserved for much smaller projects, “like staircases and decks.” When ETP argued that less than 1 percent of all oil spills from pipelines result in any environmental damage, even Owen, representing NABTU, a friend of the project, responded: “But isn’t that statistic meaningless if we do not know how many oil spills happen overall? If there are 5,000 oils spills a year, that could be 50 spills that do damage the environment.”

Getting Beyond the Roles

After almost a full hour of discussion—we have 90-minute classes—there were still hands in the air and passionate arguments, but we closed the meeting. We wanted time for students to reassume their own identities so they could write and reflect on what they had learned from the role play and their current thinking on the pipeline. We conceived of this as a way for students to transition out of their roles.

For some students, this transition can be difficult, but it was a necessary step to achieve our goal: for students to construct a deeper understanding of the issue, not one that had been provided for them.

Students’ opinions varied considerably, although a majority opposed DAPL. Alexander reasoned the pipeline wasn’t safe: “Though it seems impressive that 450,000 barrels of oil will be transported daily, this also means that one spill will result in an incredibly large amount of oil leaking into groundwater and rivers.”

Kai focused on long-term climate effects: “I think the greenhouse gases in our planet are dangerous. If we do not act on the renewable energy alternatives sooner than later, we will eventually reach a point we cannot come back from.”

Many students homed in on historical injustices to Native Americans. For example, Samantha wrote, “The Sioux have spiritual connections to the land that’s being tampered with and it’s really unfair after all the sacred land that’s already been taken from them.”

A number of students who supported the pipeline were compelled by the pipeline’s purported economic benefits. Amy wrote: “I think the pipeline building should not stop because our society is dependent on oil and we will become more independent from getting our own oil our own way. . . . Oil prices will go down, the amount of oil will go up and get to consumers more quickly, which benefits our economy.”

Even though we asked students to share their own ideas at this point, we realized that some students were repeating the information in their roles. Students who had played the NABTU, for example, were much more likely to write about the good, high-paying jobs associated with pipeline building, while students who played Iowa farmers were more likely to write about the pollution caused by oil spills and the unfairness of eminent domain. We realized how important it was not to conceive of this role play—and the follow-up writing—as a stand-alone unit. They are an entry point, not a destination.

History in the Making

When we were developing this Standing Rock lesson, we had no idea how things would unfold. But December 4, 2016, brought some good news for the Indigenous water protectors and their allies. The U.S. Army announced its decision not to grant an easement for ETP to cross under Lake Oahe. A detailed letter by JoEllen Darcy, assistant secretary of the Army, invoked treaty rights, called for a full environmental impact statement, admitted that outcomes of earlier environmental studies had been (improperly) withheld from the tribe, and initiated a robust exploration of alternatives. During the campaign, candidate Trump publicly stated his support of DAPL and, on his fifth day as president, issued an executive order to “expedite” the review and approval of the pipeline. His administration moved quickly to backtrack on the commitments the Army made on Dec. 4.

This reversal is just the latest instance of a promise made and broken. During the negotiations that would result in the 1744 Treaty of Lancaster between the colonial governments of Virginia and Maryland and the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, Onondaga leader Canasatego testified: “We are now straitened and sometimes in want of deer, and liable to many other inconveniencies, since the English came among us, and particularly from the pen-and-ink work that is going on at the table.” The wonderful phrase “pen-and-ink work” referred to the treaty that was being written as Canasatego spoke. It captures the duplicity that characterizes the history of treaty-making between Indigenous peoples and European and U.S. invaders: Government officers plying Indigenous negotiators with alcohol, providing documents in languages they could not read, or getting signatures from individuals who had no authorization from their tribe. The U.S. government has never stopped using bureaucratic and pseudo-legalistic tools to obscure the negative consequences of these treaties on the Indigenous people affected by them.

The situation in North Dakota has had its own “pen-and-ink work”: ETP’s insistence that it carried out a “thorough” environmental review; the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ acceptance of the Nationwide 12 permit, which amounted to fast-tracking DAPL; the refusal, by most media and the government, to take seriously the legal meaning of “unceded lands” in the history of U.S.-Sioux treaty-making.

Our job is to help students develop the skills and access the resources to cut through this “pen-and-ink work” so that they can fully participate in the national—and international—discussion of what should be done about DAPL. Although these lessons focus on a single pipeline during a particular historical moment, the issues raised are large, relevant, and timely: Indigenous rights, environmental racism and justice, organizing and resistance.

So even as the Army Corps announcement initially brought much celebration, it will take vigilance on behalf of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, the water protectors, and their allies, to hold the line. Their demands are clear and uncompromising: water is life, defend the sacred, and #noDAPL. Our teaching must be just as clear and uncompromising in its insistence that the voices of this movement take center stage—at least for a while—in our curriculum and classrooms.

Resources

- Materials for the Dakota Access Pipeline Role Play available at the Zinn Education Project website: zinnedproject.org/materials/standing-with-standing-rock-nodapl.

- Archambault II, David. Aug. 24, 2016. “Taking a Stand at Standing Rock.” New York Times.

- Calloway, Colin. 2012. First Peoples: A Documentary Survey of American Indian History. Bedford/St.Martin’s.

- Chiang-Waren, Xian. Sept. 16, 2016. “Inside the Camp that’s Fighting to Stop the Dakota Access Pipeline.” Grist.