Standing Up for Tocarra

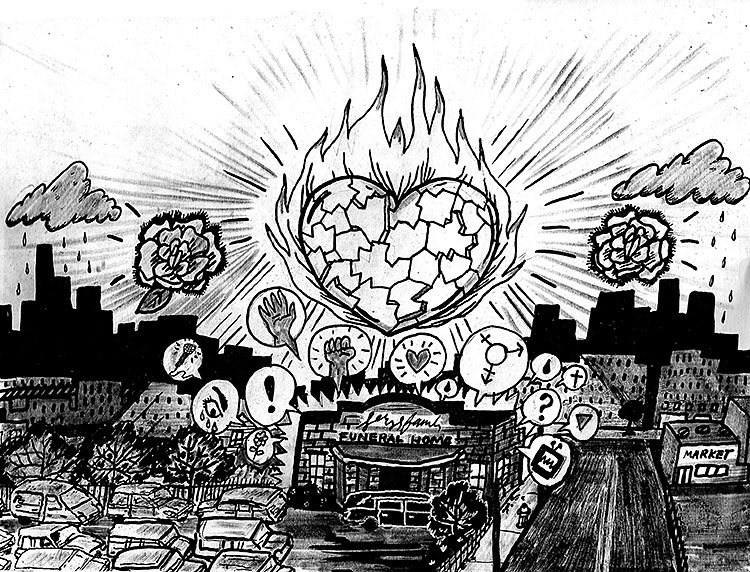

Illustrator: Katrina Clark

In the fall of 2005, a group of teachers opened the Alliance School of Milwaukee. Many of us on the planning team had witnessed the discrimination and homophobic harassment of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth in traditional schools, and it was our intention to create a place where it would be “OK to be black, white, gay, straight, gothic, Buddhist, Christian, or just plain unique.” What we didn’t know was how far outside those doors we would have to go in standing up for our students.

Tocarra was one of my students at the high school where I taught before starting Alliance, and she was one of the reasons I felt so passionate about the mission of the school. A transgender student who was just starting to transition when I first met her, Tocarra was lucky to have great family support, and she was very proud of who she was. But at the large high school, she was being harassed and threatened every time she wore women’s clothes to school. She would often come to my room between classes to take a “safety break” before moving on to her next class. According to the administrators, they couldn’t stop the students from harassing her. “If she would just stop dressing that way, she wouldn’t have these problems,” they said. Tocarra was on the brink of dropping out of school, but when she learned about Alliance, she hung on and transferred to the new school as soon as the paperwork could be turned in. And she played a key role in our final planning. Her voice influenced everything we did.

When the school opened, students came from all over to attend, and most of them didn’t know each other before they walked through our doors. Some of the students who enrolled came for the mission, and others came because there were seats available or because Alliance started with the letter A so it was the first school listed in the school selection book. Our first year was an interesting one. There were students from every different background and ability group. There were students from the city and students from the country; black students and white students; poor students and wealthy students; gay students, straight students, and everyone in between. We had to do a ton of work to build connections among the different groups of students.

Tocarra welcomed everyone and wasn’t afraid to teach others what it means to be transgender, so she played a big role in bringing an understanding of transgender reality to the Alliance community. She was patient with those who didn’t get it, teaching rather than chastising them when their words were hurtful, and she stood up for everyone who needed a defender, not just those students who were most like her.

One day she was checking out my outfit (a long, princess-style coat with fur trimmed hat and cuffs) and she said, “Ms. Owen, when I become a woman, I want to be sexy like you – sexy classy, not sexy slutty.”

Tocarra always knew just what to say to make someone feel beautiful, so it was no surprise that in a very short time she was well loved by the entire Alliance community. She became a mother figure for many of the students and a role model for some of the younger transgender students. She had a flair for fashion and a desire to be not just noticed, but adored, and adored she was.

Then, late one evening that first year, I received a call from one of the students. “Is it true?” she asked through her tears. “Is Tocarra dead?” She had received a text message, but I hadn’t heard from anyone, so I told her I would call back as soon as I found out what was happening. I soon learned that it was true. Tocarra had suffered heart problems in the middle of the night and had passed away. She was 18 years old.

I called the staff together for a meeting at my house. We cried together, talked about how much we would miss Tocarra, and then made a plan for how we would talk to the students the following day. We decided to have a community meeting first thing in the morning and assembled a crisis team of social workers and support staff for any student or staff member who needed to talk. I knew I was going to need their support as much as anyone.

The students were devastated when they learned about Tocarra’s death, and I spent much of that morning comforting students who fell apart in my arms. It just didn’t seem possible. Tocarra had been fine just days before. She had even flown to New York two weeks earlier to tape a Jerry Springer show, one of those “my girlfriend’s really a man” episodes with lots of silly fight talk and drama. Before she went, she had asked my opinion about participating. I told her she should do what she wanted, but to remember that people already perceive the transgender community in negative ways, so she should try not to reinforce stereotypes. She wasn’t one to take her role in the community lightly, so she went back and forth about whether or not to be part of the show. In the end, her desire to be a star, if only for a moment, won out, and she headed to New York.

Most of Tocarra’s family lived in Chicago, so it made sense that they would plan to have her funeral there. Many of our students and staff members wanted to attend, so we arranged for a bus to take us. More than half of the student body rode the bus that day to attend the service, including Tocarra’s dearest friend Jade, who was also transgender. As she walked into the funeral parlor holding my arm, Jade looked like Marilyn Monroe in her blonde wig, black dress, and sunglasses. Despite the questioning looks from other people at the service, she walked into the room with all the pride, beauty, and anguish of a mourning widow.

We arrived just in time to fill up the seats of the small funeral parlor that had been reserved for Tocarra’s service. It was a sad-feeling place, a room that didn’t expect to have many guests for the likes of someone like Tocarra, and I couldn’t help but wonder if it had ever been as full as it was that day.

The viewing was almost unbearable. The person who prepared Tocarra for the visitation must have looked only at what was between her legs to determine how to dress the body, and never considered what gender may have been in her heart. To our horror, when we walked to the front of the room, there was Tocarra dressed like an old man in a suit and tie, lying in the casket looking like someone we had never met.

Jade was furious. “What the hell?” she said, pointing at the casket and searching the room for who might have been responsible. Finding no answer in the line of people waiting to see the body, she stood up tall and walked angrily to the back of the room, where a few teachers and students stood, huddled in communal fury over what they had seen and discussing what Tocarra would have wanted instead.

When it was time for the service to start, we moved to our seats. My daughter and her best friend sat close to me, arms threaded through mine, tissues in hand, still in shock from the viewing and the loss of their sweet friend.

Things only got harder when the sermon began. The minister did not know Tocarra. He kept calling her by a boy’s name that wouldn’t have been correct even if Tocarra had wanted to be called by her boy name, and I cringed every time he said it. He was a traditional, homophobic, Baptist minister who preached a sermon that condemned Tocarra to an eternity in hell rather than raising her up for her family and friends. It was as if he was telling us, “I know what he was, and this is a warning for all of the rest of you.”

I was outraged for Tocarra, and I wanted to cover the ears of my students so they wouldn’t have to hear the fire-and-brimstone hate coming from his lips. Many of them had experienced that kind of religious condemnation personally; they knew exactly what was happening, and I could feel them crumbling inside. The more he preached, the more upset they became. Soon the ones sitting close to me, including my daughter and her best friend, started nudging me. “Do something,” they whispered. “He can’t talk about her like that. He’s wrong.”

They were right. I couldn’t stand it any longer, either, so I did something I never imagined I would do – I raised my hand and asked if I could speak. The minister looked from me to Tocarra’s family. I asked them directly, “May I speak?”

Tocarra’s mother nodded to me, uncertain but hopeful, the weight of the minister’s words too much for the young mother who had already lost her child in this world, and couldn’t bear the thought of losing the promise of seeing her baby in the afterlife as well. “Please,” she said, and the other members of her family nodded.

I went up to the pulpit and started to talk about Tocarra as I knew her. I spoke about the young woman who was loving and accepting and funny, and who never gave up on anyone. I spoke about the person who had helped to build our school with her great ideas and insights. She would never be forgotten by any of us. And, most importantly, I spoke about how Tocarra had earned her place in heaven with her loving ways, her joyful spirit, her commitment to helping others. I reassured her family and her friends that they need not worry, because we would all see her there someday. If anyone deserved a place in heaven, it was Tocarra.

When I was done, I invited her family and friends to come up and speak. Her mother came first, and then her brothers, and then friends and teachers lined up to share their memories. We laughed, cried, hugged each other, and sang her blessings to the universe. It was beautiful, and I’ve never felt as proud of anything I’ve done. So many people lined up that eventually the minister had to stop the line and ask people to save their stories for the burial, because there were other services that had to take place in that room. I think he was angry, but he didn’t dare try to change the story that had grown, because people were emboldened now and they weren’t about to let him pin the weight of sin back on the life of the young, beautiful spirit of a woman they had known.

That afternoon, I rode the bus back to Milwaukee in silent sadness, exhausted by the past several days of holding myself together for the students and staff. So many thoughts ran through my head as we traveled. I grieved for the loss of this young person who had become such a central figure in my life. I mourned for what the world had lost, someone who really could change the world and make it better. I wondered about the courage that had lifted my hand in that moment when I couldn’t take the minister’s words any longer. And I prayed for Tocarra and for all of the fabulous transgender souls who had gone to rest in less than fabulous fashion.

A few days later, the school community gathered in the community room to watch the Jerry Springer show that Tocarra had gone to New York to record. We were nervous but excited to see her alive on the television screen. I’ll admit that I hadn’t wanted her to be part of that show. But as we sat and watched that silly episode, where at one point one of her balloon breasts fell out of her shirt as she attempted to “fight” with her boyfriend’s girlfriend, I couldn’t help but laugh. Tocarra was such a great spirit – so bold, so funny, and so full of love. Although the show was as outrageous as expected, it was good to see Tocarra one last time as she would have wanted us to remember her – sexy classy, not sexy slutty – and beautiful to the core.