“Song for Tamir Rice”

Learning and Teaching Music as a Catalyst for “Coming to Voice”

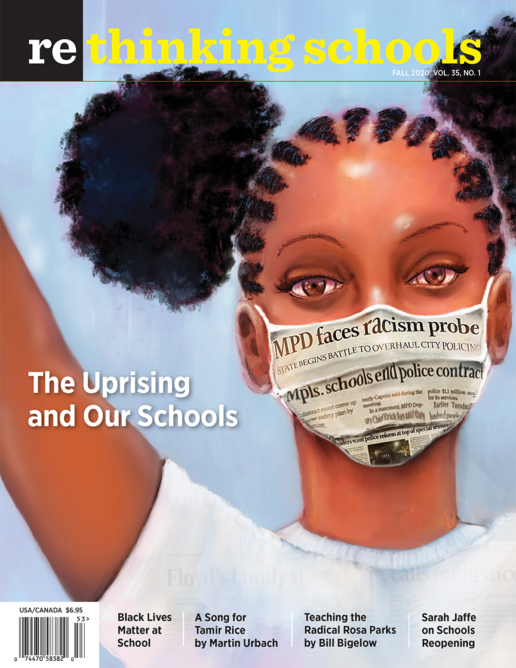

Illustrator: Keith Henry Brown

Tamir Elijah Rice was a 12-year-old murdered by a white Cleveland police officer in 2014 who was responding to a 911 call about a male pointing a gun at random people at a park in Cleveland. The caller mentioned that the gun was “probably fake” and the person was “probably a juvenile.” Footage shows that Tamir was shot by police before the squad car even stopped. He had a toy gun, an airsoft replica. The officer who murdered him had previously been fired from another police department for being emotionally unstable. In 2017, the officer was finally fired, not for murdering a kid, but for lying on his job application.

On Thursday, June 25, 2020, New York City high schools held their virtual graduation ceremonies online due to COVID-19. Tamir would have been 18 years old on the same day as the teen musicians that I teach graduated high school. As my students flipped their tassels to the right, and celebrated one another for their accomplishments, I reminded myself that Tamir should have been afforded the same opportunity: the chance to attend his high school graduation, even if it was a less than exciting webinar. He should have been afforded the chance to self-realize and to not be murdered by state-sanctioned anti-Black violence in the form of police terror. During our Zoom ceremony, we acknowledged Tamir’s life by holding a moment of silence, naming that he should have been with us, naming who murdered him, and naming who acquitted his murderer. We mourned and healed together and chanted a call-and-response a few times: “Say his name.” “Tamir Rice.”

I teach at Harvest Collegiate High School, an integrated, progressive, restorative justice-based public high school in New York City. As an abolitionist, anti-racist music educator, I aim to place music teaching, playing, and learning in the social, historical, and political contexts in which music occurs.

Every movement for social justice in the world has had a soundtrack. From Miriam Makeba and Hugh Masekela in South Africa, to Violeta Parra, Sergio Ortega, and Víctor Jara in Chile fighting fascism, to Mahalia Jackson, Nina Simone, and Harry Belafonte during the Civil Rights Movement, to Kendrick Lamar, Janelle Monáe, and Lauryn Hill in times of Black Lives Matter. Soundtracks elevate the messages of movements and images, and give them a new kind of meaning.

The concept of “coming to voice,” originally coined by bell hooks, is central to my teaching. We live under a system that thrives on silencing people. In the pursuit of teaching music for social justice activism and for “coming to voice,” I search to uplift stories that I believe that students will “vibe with.” I look for songs that can be both mirrors and windows for my students to engage in their own journeys of “coming to voice.” In finding “Song for Tamir Rice” by the Peace Poets, I found a song that can act as both. The song is a mirror because students can reflect on how they fit in with the narrative, connect to Tamir’s story in a deep way, and connect to their own feelings, thoughts, and voice. It also acts as a window for students to see “what’s out there,” to learn what others in the world have to say about this injustice, and to connect to the world at large.

Teaching “Song for Tamir Rice”

On Nov. 22, 2018, Tamir Rice would have been 16 years old. That day, I started the circle/class by telling students I had been touched by a music video based on a song by the Peace Poets. The Peace Poets are a New York City-based collective of poets, hip-hop performers, and educators who respond to social and political crises through spoken word poetry, rap, and music. The Peace Poets are frequent guests in my classroom, and I am a guest in their performances in the community.

In the video (bit.ly/TamirSong), protesters stand side by side in front of a court building singing “Song for Tamir Rice,” and holding protest signs that read “Justice for Tamir” and “Resist Racism.” I love how the one-minute video allows students to see and hear a community coming together in grief and solidarity to protest the tragic police murder of a Black child; it also shows power of song to unite people and amplify messages.

When it was over, I asked: “How are you feeling?” A hush fell over the room. I didn’t push for an answer. I knew that if they knew how they were feeling, they’d tell me. So, I followed with “What do we know about Tamir Rice?”

Isaiah said: “That he was very young when he was killed by police.”

Andie added: “He had a F’ing toy gun.”

Students also made connections with them being older than Tamir was when he was murdered. They made connections with Tamir’s experiences of being a young kid of color. I listened and stayed attentive to students’ feelings and energies.

As students watched the video a second time, they jotted down thoughts on Post-it notes. I typically ask students to write down their thoughts when we listen to a song or watch a music video as a way to encourage them to have private moments of self-reflection. Most student comments focused on the content and feeling of the message, such as “not right,” “sad,” “powerful,” “#BlackLivesMatter.”

I posed the following question and asked students to not answer it, just to think about it as they began learning the song:

How can we use music to explore and show the ways in which we are bound to one another in the struggle toward collective liberation?

Then we learned the words and sang along to the video by rote — by repeating the words over and over. I reminded students that in musical cultures that are not Eurocentric, folks learn music by listening, rather than reading, and musicians often learn tunes through repetition. (Students who benefit from having the words written could transcribe the words either on a flashcard or the “notes” app on their smartphones.)

When I asked Frankie Lopez from the Peace Poets during one of our community singalong workshops about how they teach chants to communities, he said: “You have to trust the people’s abilities to carry a song alongside each other. We have to make space for people to learn a song through repetition, and if someone forgets one part, someone else steps up and leads. Through this process, the community learns the song quickly, and it develops a sense of belonging.” I shared Frankie’s words and added: “Think of it as a meditation. We put strong words in our breath. We say powerful words — words matter. We become truth tellers through song.” We must have listened to the song 10 to 15 times, singing along with the video and one another:

When a mother is mourning

and you hear her say

she wants to see this government

investigate this case

A mother’s cry for justice

Can you feel her pain?

Oh, Tamir, Tamir

We feel you here

Waking up the DOJ

Oh, Tamir, Tamir

We feel you here

Waking up the DOJ

The students pulled out their smartphones and googled what DOJ (Department of Justice) meant. We talked about why it might be that as 15- and 16-year-olds they might not know how such an important part of our government works. “They don’t teach us what they don’t want us to know,” Brian added.

Next, I asked: “How are we bound to one another’s liberation/freedom? What can we come together to do as musicians?” AJ, one of our singers, said: “We can add melody and rhythm to already powerful words, and we can also add energy, vibe, and the spirit of the ancestors when we put music to words, speeches, and chants.”

Angel said, “We could make up chords to this chant.” He grabbed a guitar and his bandmate, Jenn, grabbed her bass and they began finding the beginning notes of the chant. She interrupted, “This song should be sad but also powerful, like a war call.”

Then Andie, a guitar player, said he had been working on blues-inspired riffs. Riffs are collections of a few notes that are memorable, short, and sweet. Keyboardist Steven decided to start the chord progression on D minor, so Andie improvised the riff on his guitar: C-D-F-G-F-D. The singer, Cee, played around with the melody while adding embellishments and keeping a sad, yet hopeful texture to her voice. When debriefing, she said: “Hope is the most important part of this song’s message.”

The only “formal” music instruction I did was regarding the i-V7-i chord progression. Chord progressions are a part of what is called harmony when we talk about music theory. Chords are simply the blocks of sounds underneath melodies in songs. The chords support the melodies by providing pads of typically three notes that “sound good” or “in tune” with one another because they belong to the same scale. Think of them as belonging to the same family. Typically, a I (one) chord sounds like “home,” somewhere we recognize, are comfortable, and where the music sounds most stable. When we write that I (one) chord in lowercase, it refers to a minor chord. The simplest way music teachers have taught the difference between major and minor chords to kindergartners across the globe is “Major keys sound happy and minor keys sound sad.” This is not always the case, but it is a good generalization nonetheless. The D minor chord, or the one chord, is D, F, and A in the key of D minor.

The V7 (5) chord is a “dominant chord,” a chord that leads us both away and back to home. The V7 in this case is an A7 chord. Seventh chords come from the tradition of the blues. The seventh chord is a bigger chord, has four notes instead of three, and includes the minor seventh degree of the scale, giving the chord a “bluesy,” dominant sound that produces lots of tension.

When one plays a chord progression that begins with the chord (i) or home, goes to the chord (V7) or dominant/tension, and goes back to the chord (i), we get to experience both tension and release. It is a perfectly balanced sound that both makes us feel uncomfortable and puts us at ease within the span of a few beats.

Students talked about the i chord, in this case D minor, being “home” or “Tamir” and the V7 dominant chord being “A7” or “redemption,” ‘justice,” “no more Black kids dying at the hands of the police,” somewhere we yearn to reach. We then brought it back to D minor i chord.

As the students and I worked for about two hours making this song, we talked about police brutality, teenagerhood, racism, music, school, and hope for a different kind of world. We began the arrangement of the song with deep, slow, and low drum hits mimicking steady stomping or marching in a somber tone. Then the guitar and bass entered the song by strumming open D minor chords and adding vibrations to their chords by shaking the necks of their instruments. Ryan, one of our drummers, added swells of cymbals with a pair of homemade mallets he made by attaching a pair of socks to drumsticks. After a few cycles of us playing the song instrumentally and creating a somber vibe to embody the sounds of “mourning,” Cee began singing the words over and over, increasing the intensity in each cycle, borrowing nuance and techniques from singers Aretha Franklin, Nina Simone, and H.E.R. During one of the final cycles, Isaiah, our guitarist, intersected the lyrics by playing a distorted guitar solo line underneath the words and adding an element like a wail, thus creating the climax of the song’s remix. At the end, we documented a performance of our version of the song.

Now, in 2020, in the midst of a pandemic, an election year, a global racial justice uprising to protest anti-Blackness and state-sanctioned violence at the hands of the police, I continue to ask: What does it mean to use music to feel, process, and be transformed? We write songs that change us first so that we can then change our world. In Parable of the Sower, Octavia Butler writes: “All that you touch you Change. All that you Change Changes you. The only lasting truth is Change.”

The group of students who worked on this project continue to be a band, struggling together through the hardships of teenagerhood, mental health, and now COVID-19. After doing this project, we did a few others, including chanting and protesting together during the walkouts for climate change and creating a punk rock version of the song “I Can’t Keep Quiet” by the artist MILCK from the Women’s March in 2017.

I have also changed. I keep changing my understanding of what it means to stay engaged as a music teacher, as a youth organizer, and as a co-conspirator of racial and economic justice. I aim to keep doing this work inside my school, making and teaching activist, socially conscious music alongside my students — beating, bucketing, chanting loudly through cheap megaphones outside in the streets alongside my students and our communities. And, most importantly, I continue doing this work in the classroom to see my students change and become more socially conscious — to stand alongside them in our journey of “coming to voice.”

An earlier version of this article appeared as a blog post on Decolonizing the Music Room. Watch Urbach and his students perform the song at bit.ly/TamirSong2.