Six Ways U.S. History Textbooks Mislead Students About the History Between Central America and the United States

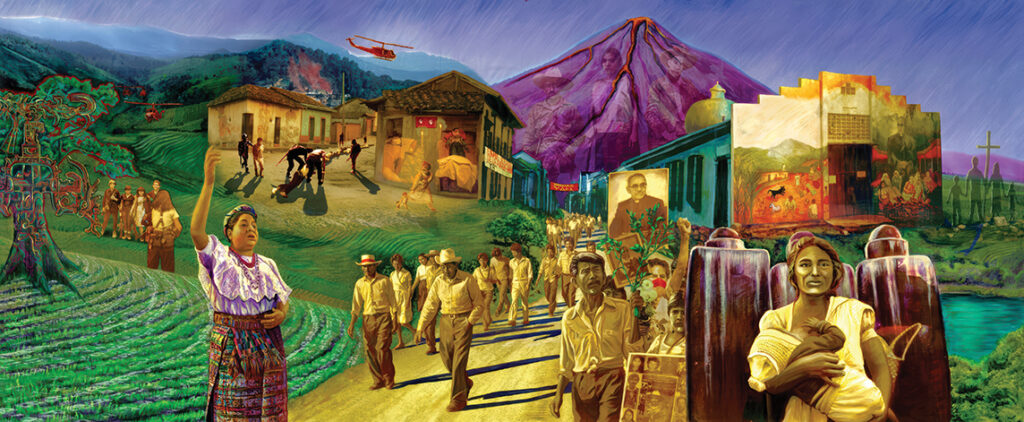

Illustrator: Judy Baca

Image courtesy of the SPARC Archives, sparcinla.org

Central America has long been an overlooked target of U.S. exploitation. Over the last 200-plus years the United States has conducted countless invasions and massacres, funded and trained military regimes and death squads, and extracted maximum capital from the isthmus. The United States claimed Central America as its “backyard,” fostering a sense of entitlement to control and profit from the region. U.S. history textbooks do not properly explore this history, or they misrepresent it. Without this history, it becomes harder to understand the United States’ role behind current and historical waves of migration and the economic and political complexities from and in these countries.

Central Americans are the second largest Latinx group in the United States, with Salvadorans alone making up the third largest country group. This means that Central American students are in the classroom, reading these textbooks, and learning misleading narratives about themselves and the U.S. role in bringing them here. Textbooks also silence the U.S. government’s role in creating the immigration crisis, stoking xenophobia. History is made daily, so not righting the wrongs of the past allows for similar or even worse atrocities to be repeated. These legacies continue unless we recognize the patterns.

We reviewed 10 U.S. history textbooks with publishing dates ranging from 2012 to 2023 from well-known publishers such as Pearson, Cengage Learning, Holt McDougal, Prentice Hall, and Norton Publishing. These books revealed the following failings:

1. Textbooks decenter Central America in the frame of its own history.

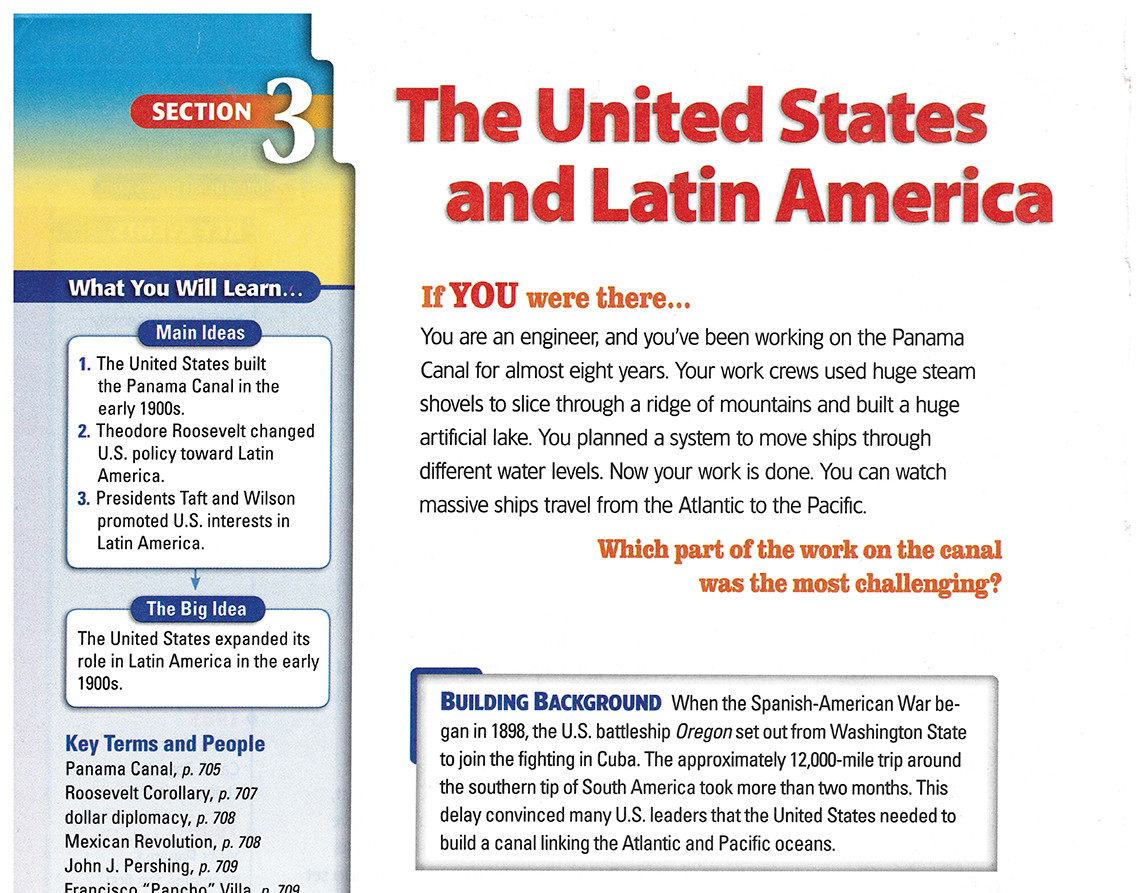

Textbooks often begin sections or use headings that decenter Central America in their framing of events. For example, in Holt McDougal’s United States History, the section on the United States and Latin America opens by encouraging students to imagine themselves as the engineers who oversaw the construction of the Panama Canal. This directive immediately places students in the role of the white, U.S.-based, well-compensated few, inviting them to empathize with the privileged who oversaw the canal project and to ignore the thousands of Black Caribbean laborers who deserve the recognition for building the canal.

Beginning the section on the United States and Latin America by having students imagine themselves as the U.S. imperialist and profiteer sets a precedent for how students approach the rest of the content, aligning themselves with U.S. elite perspectives and decentering Central America. These instructions and framing entrench the idea in students’ minds that the United States is “us” and Central America is “other.”

Similarly, many texts frame Central American aspects of important moments in U.S.-Central American history, like Nicaragua in the Iran-Contra Affair, as marginal rather than as central to the narrative. Textbooks discuss the Iran-Contra Affair under headings such as “Trouble Persists in the Middle East,” “The Middle East and Terrorism,” or “Interventions in the Middle East,” signaling to students that the “Iran” part of the “Iran-Contra Affair” is what they should pay attention to. This spreads the notion that funding the Contras was a side quest, secondary to attempts to free the hostages in Iran and puts the Sandinista movement and Reagan’s support for the Contras on the backburner, decentering Central America in one of its key historical moments.

Similarly, textbooks often put U.S. interventions in Central America in the 1980s under subheadings about Reagan-era policies. This encourages readers to think that this history is Reagan’s story rather than the story of Central American people who survived or perished as a consequence of U.S. intervention. Furthermore, this framing implies that tensions between the United States and Central America existed only under Reagan. In fact, these exploitative relationships date back centuries and continue into the present.

2. Textbooks omit large portions of Central American history.

We cannot teach what we do not know. Of the books reviewed, zero mentioned Belize (unsurprising given the relative lack of U.S. intervention in Belize), two mentioned Costa Rica, four mentioned Honduras, seven mentioned El Salvador, nine mentioned Nicaragua, nine mentioned Guatemala, and 10 mentioned Panama. By mention, we mean that the word was present in a paragraph (not on a map), not that the countries were discussed in depth. An example of this omission is History Alive! The United States Through Modern Times from TCI, which, out of all U.S.-Central American history, only discussed the Panama Canal, and the 1954 coup d’état against democratically elected President Árbenz of Guatemala with minimal detail. Books overlooked the role of the United States in 1970s and ’80s Central America through the funding of repressive regimes in El Salvador, Guatemala, and the Contras in Honduras against the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, or the role in training death squads, and the increase of anti-communist sentiment. The omission of Honduras is notable because of how important it was to the United States in the 1980s: the Soto Cano Air Base, the funding of the Contras against Nicaragua, funding for death squads like Battalion 3-16, and providing training from the CIA. Honduras was a vital part of U.S. interference in Central America to the point where people started calling it USS Honduras. U.S. students learn none of this history from textbooks.

When talking about Manifest Destiny, all textbooks included westward expansion, but they made little or no mention of southward expansion. As the exception, a fraction of books briefly mentioned William Walker, the “filibusterer” who took expeditions to Central America and parts of Mexico to gain power and establish Central American countries as enslaving U.S. colonies. So strong was his grip that he managed to become president of Nicaragua from July 1856 to May 1857, a government recognized and legitimized by U.S. President Franklin Pierce. He was taken out of power and ultimately assassinated in Honduras where his remains reside. In today’s Central America, Walker is a symbol of U.S. imperialism, but textbooks seldom teach his history.

Texts almost completely omit important drivers of economic inequality and land dispossession. A few books have a small section on the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), but none mentions the Central America-Dominican Republic Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR), a free trade agreement that has gutted local farmers and facilitated labor exploitation and land encroachment, as well as immigration by driving people north.

Perhaps the most obscene omission is the lack of integration of Central American people besides a few presidents. Within this omission, textbooks obscure the multiracial nature of Central America, homogenizing the region, failing to discuss Indigeneity and Blackness in the isthmus. In the same vein, books omit U.S. Central Americans and the U.S. role in their migration.

3. Textbooks treat Central American history as a footnote.

When U.S. history textbooks include portions of Central American history, these are relegated to the literal margins. The textbook Give Me Liberty! An American History from W. W. Norton & Company, despite adding new details like the El Mozote Massacre in El Salvador, dedicates only half a page and a map to 1980s Central America. Half a page or less is commonly used to discuss immensely complex regional conflicts.

Give Me Liberty! dedicates an entire 10-page section to Vietnam, but only two sentences to El Salvador and Guatemala combined. This is not unique to Give Me Liberty! Some textbooks devote a full chapter to Vietnam yet spend only a few sentences discussing Cold War-era conflicts in Central America. Some may argue that Vietnam is more important to U.S. history because 58,000 U.S. soldiers died and the divisiveness of the anti-war movement. Despite solidarity movements, Central American conflicts did not grab U.S. public attention the same way, making Central America less prominent than Vietnam. However, Central America has a centuries-long history of entanglement with the United States, including hundreds of thousands of deaths in Guatemala alone, and numerous other massacres across the other six countries. When a textbook uses a few sentences to represent decades-long conflicts — conflicts that the United States helped inflict — the long-lasting trauma and resistance of Central American people is erased. The United States gets to move on. Central Americans do not get this luxury.

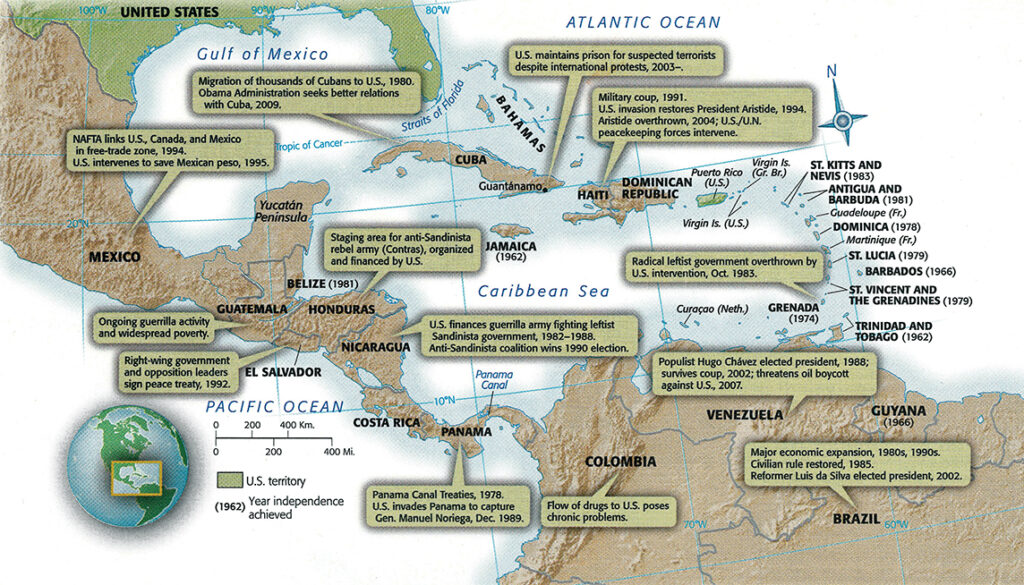

U.S. history textbooks are filled with maps like the one above, which give important information, but lack context not found in the map or in the text. Complex histories get consigned to a word bubble on a map that lacks nuance and that students will likely not read. Those word bubbles could easily be expanded and put into a section or chapter, but Central American history is not a priority.

4. Textbooks perpetuate harmful stereotypes about Central America.

Textbooks often employ a biased, nearly prejudicial tone when discussing Central America. Prentice Hall’s United States History: Reconstruction to the Present, Mississippi edition, quotes a U.S. ambassador calling El Salvador “rotten” (p. 752) in the context of the 1980s civil war that the United States heavily funded. The book’s repetition of this biased quote upholds the false stance of moral superiority that the United States took against the Salvadoran government, as if the United States was not responsible for funding the atrocities that made El Salvador “rotten.” Paired with the fact that textbooks almost never mention Central America positively, quotes like this promote the stereotype that Central American people and governments are deficient and inferior.

Many textbooks define Central American regimes by how “friendly” they were to the United States — even if they killed their own citizens and were installed or propped up by the United States. These examples illustrate a false objectivity that disregards Central American lives and prioritizes glamorizing or sanitizing war crimes as long as those crimes align with U.S. interests.

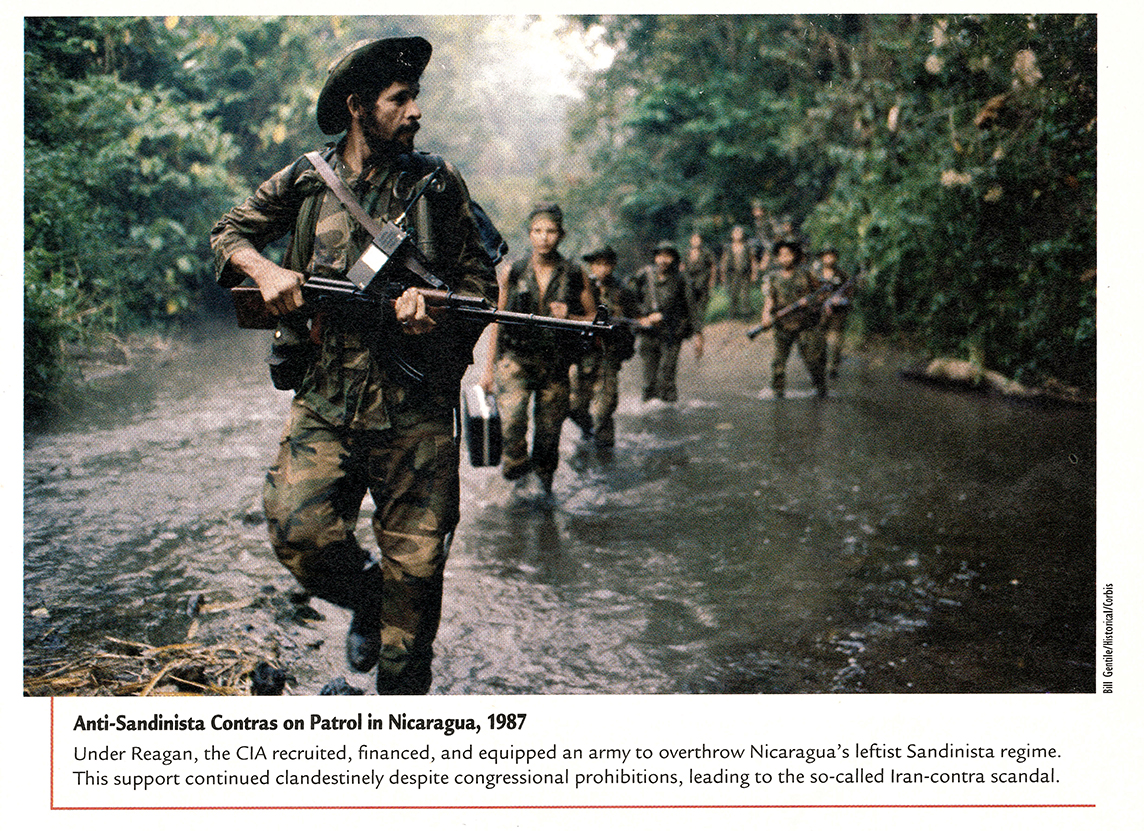

Lastly, the anti-Central American bias and stereotypes in textbooks are prominently displayed in their lack of diverse photos of Central Americans. Across all the books we reviewed, few contained photos of Central Americans; if they did, Central Americans were almost exclusively portrayed as violent guerrillas. The photo below of heavily armed Contras from Wadsworth Cengage Learning is an example.

(Wadsworth Cengage Learning)

5. Textbooks privilege U.S. imperialist interests over Central American critiques.

Textbooks consistently center U.S. imperialist interests in their recounting of history between the United States and Central American countries, erasing Central American countries’ autonomy and desire for freedom from interference. Nearly every textbook reviewed describes U.S. interventions in Central America in terms of “maintain(ing) stability in the region and protect(ing) the Panama Canal,” “protecting U.S. interests,” maintaining “stability, security, and U.S. Supremacy,” “protecting American investment,” or by referencing the Roosevelt Corollary’s position that Central America needed to be “policed.” Although U.S. historical figures may have stated these were their motivations, history textbooks have a responsibility to provide more context by explaining how U.S. corporate interests stood to gain financially from these interventions and the impacts these interventions had on Central Americans.

None of the textbooks in this review accomplish either of these responsibilities. Instead, most repeat the myth that U.S. policies and interventions were noble missions of self-defense. Texts vaguely reference Latin American and Central American displeasure with the United States, but do not detail the horrors imperialism brought upon Central Americans. Many textbooks contain unfocused mentions of U.S. actions causing “long-term resentment against the United States” or “poor relations with the entire region of Latin America.” Similarly, some textbooks offer weak mentions of returning the Panama Canal to Panama “to end bitterness” or “to remove a sore point” in U.S.-Latin American relations.

The issue with these statements about Central American anger, and more generally Latin American resentment against the United States, is that none properly explains why Central America was angry with the United States. A textbook might mention that the CIA-backed coup that overthrew the elected president of Guatemala “successfully prevented Guatemala from becoming communist” (which entirely misrepresents the situation), but it gives readers no indication that this led to a decades-long civil war and the genocide of hundreds of thousands of Maya people. This and countless other indignities and atrocities that the United States inflicted upon Central America are never explained from a Central American point of view. Textbooks foreground U.S. imperialist goals of “self-defense,” making the United States the subject and Central America the object, capable only of being acted upon.

6. Textbooks minimize U.S. atrocities in Central America.

Not only do textbooks center the views of U.S. imperial powers, they also minimize the extent to which the United States imposed its power and violence on Central American countries. Many of the sections recounting the imperialist history of Central America give half-truths or lack context about the significance of U.S. interference in the isthmus. This is especially visible in 1980s Central America, under the context of the Cold War, where the textbooks undermine the severity of U.S. interventions. The books often mention sending aid to El Salvador but not the amount. In truth, the United States sent more than $5.5 billion, far exceeding regular spending and symbolizing the stakes present for the United States in the war. The textbooks mention the human rights violations but not the U.S. training of the troops who committed the violations, including scorched-earth tactics. Similarly, textbooks minimize the extent of U.S. involvement. The death count for the 1989 U.S. invasion of Panama, also known as Operation Just Cause, varies widely across textbooks, ranging from 300 to 4,000 civilians. Crucially, none of the textbooks cite their sources for the death count.

A number of texts fail to mention the United Fruit Company or describe it as simply exercising “powerful” control over Central America. However, books do not clarify that United Fruit owned half of the arable land in Guatemala, the exploitation, human rights abuses on the isthmus and Colombia, or its role in the 1954 coup of Guatemala. These mischaracterizations protect the United States’ image.

While many textbooks minimize the extent of U.S. interference in Central America, some exceptions prove that textbook publishers can do better. BVT’s Introduction to American History describes Reagan’s choice to send aid to Duarte’s right-wing government in El Salvador as “tacitly accepting a bloodstained regime.” The best example of honestly depicting U.S. interference is the Brown University Choices Program’s student text Imperial America: U.S. Global Expansion. It highlights the United Fruit Company’s legacy in Central America in a concise, yet non-minimizing way. It quickly covers the power that the United Fruit Company had over huge swaths of land, and sometimes governments, in Costa Rica, Guatemala, and Honduras. The text from Choices, however, still has room for improvement because this vital information was placed in a marginal box that many students may skip, and is still quite short, despite the content being good.

Conclusion

The dismal state of Central American history in U.S. history textbooks has remained largely the same for decades. U.S. students, no matter their heritage, need to know the history of U.S. intervention and Central American resistance. The dominant educational system props up narratives of U.S. supremacy and benevolence, encouraging students to develop inaccurate, oversimplified notions about the “good guys” and “bad guys” in history and current global affairs. Without truthful history education, students cannot develop the critical thinking skills necessary to contextualize our present migration crises, the “underdevelopment” of Central America, or to advocate for just and reparative policy.

In terms of creating tangible change, we recommend that educators teach outside the textbook as much as possible. Teachers can use resources like those found at Teaching Central America and the Central American Studies Curriculum Project at UCI History Project to bolster their curricula. For students, we recommend reading against the grain of textbooks: Be curious and always ask why. Teaching Central America also has valuable resources for students.

The history of U.S. intervention in Central America is U.S. history, and students deserve access to this history. Publishers and U.S. schools have work to do to repair the fragmentation of Central American-U.S. history.