Showing Up for Our Students in the Pandemic

Illustrator: Sally Deng

“I just want to be done. Just tell me what I need to do and I’ll do it,” Haylee wrote to me in an email. A month after school closed on March 13, her message was filled with frustration and defeat. Haylee had been pushed out to Beaverton, west of Portland, by her neighborhood’s gentrification and had to commute two hours a day to get to school. This year had already been hard for her even before the pandemic. Now, as a senior, she was desperately trying to figure out how to finish earning all of her credits without the supports she would have found walking into the school building. “I really need to graduate and be done,” she closed.

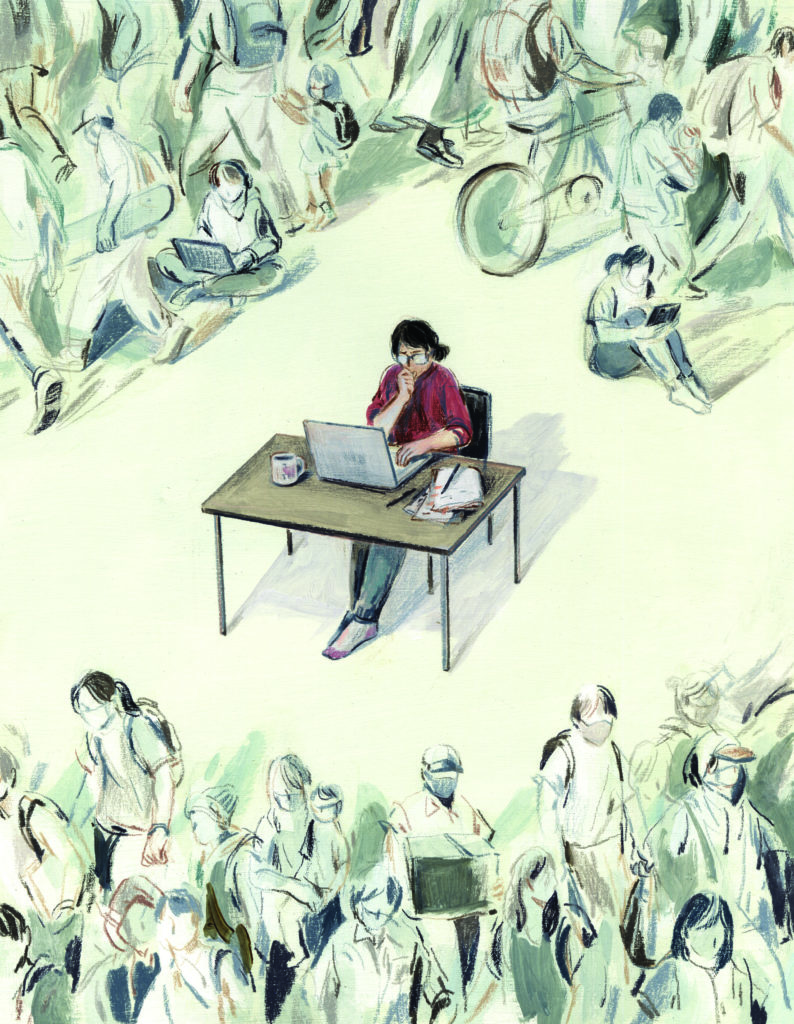

For many of my students at Roosevelt — a racially diverse, low-wealth school in North Portland — life in the pandemic has been a time that challenges their resiliency to push through so much injustice and unfairness, but also a time that challenges how we as teachers show up for them.

Kaleb, a senior who I had for the last two years, finally picked up the phone two weeks after school closed. “I’ve been babysitting my little brother every day. I can’t do anything else. My parents are either working or arguing. I know I’m supposed to do school work, but I don’t feel motivated,” he said.

Manuela, a junior who gave birth to Andres just weeks before school closed, joined a video call during office hours to show us her baby. “How are you holding up?” She gave a long sigh. “Not good,” she said. “This is really, really hard.” Her classmate, Zoe chimed in: “He is so beautiful. He’s perfect.” Trying to work up a smile Manuela responded, “He’s keeping me going. But some days are just hard.” We felt her energy and I wished I could reach over to her for a hug.

Peter, who had recently transferred to our school, joined a video call from their transitional shelter. With other teens shouting and waving from behind them, Peter asked, “Do you think I’ll be able to graduate this year? I don’t understand all the Google Classroom stuff. Can you help me?”

As I took a walk around my neighborhood, my student Diego came out of a house. “Ms. Yonamine,” he called out. “I’m sorry,” he said. “Hi, Diego! How are you?” I was so excited to see his face. “I’m good,” he said. “I’ve just been working a lot of hours. I’m fixing cars.” “Did you just start working?” I asked. “Yeah, I need to save up money. My parents are still working but I need to save up in case they lose their jobs soon. I’m really sorry that I haven’t turned anything in,” he said. My heart crushed. I wanted to make all of his school worries go away. “It’s OK. Don’t worry about it. We’ll figure it out,” I said. His words of “I’m sorry” stayed with me for days.

As students show up on occasional emails, pop in during office hours on Google Meet, or as I run into them during my nightly walks around the neighborhood, my heart squeezes for them and I want so much for them right now. School in the “new normal” doesn’t work for them. Parents are losing jobs and food insecurity ramps up. Kids ask me what they can cook on a small budget. Teachers and parents at my school helped put together a list of recipes of simple meals high schoolers can cook that included ethnic and cultural comfort foods as well as meals they can make using weekly food pantry boxes. Kids work full-time shifts; take nighttime shipment jobs or work at neighborhood grocery stores — stores that waited until the end of April to give workers masks. Some have to commute to work outside of the city, as far away as rural Sauvie Island, across the river to Vancouver, Washington, or an hour-long drive to Salem to work in fast-food chains, help with farm labor, or whatever jobs become available on a daily basis. Even more of my students tell me about their worries of eviction even though there’s supposed to be a rent moratorium.

“What if you’re undocumented? Are you still supposed to fight that? How would my family pay this all back when the rent freeze is over? What if someone finds out that we have three families in one apartment?” Mariah asked me, worried about her newborn sibling and her mother’s sleepless nights.

I asked myself over and over about my students who Child Protective Services is supposed to be monitoring. How will we know if they’re OK? How will they know how to reach us now? Most of all, I worry about the students who have gone silent — who I have not heard from since school closed. Many of these students would casually walk in during lunch or after school to mention something’s up.

Now, I go through the list of their names in my head. How are our students supposed to concentrate? And how is this “love” from a teacher when I repeat the school district’s insistence that they still need to do assignments because we’re maintaining “normal” academics?

Again and again, we hear the slogan “we are in this together.” But we’re not. The needs of many of my Roosevelt students are not the same as many in the affluent Wilson High School neighborhood across the river, and up on the hill. It’s not the same. The inequity was there before the schools shut down. And now that inequity is exacerbated. To act like my students should do the same thing academically and perform as if they can maintain some kind of school presence is an injustice — which feels like the opposite of love. School is physically closed but still continues online. Our school district instructs us, middle school and high school teachers, to “deliver roughly two hours of total student work each day” with content that is “posted prior to the meeting of class.” The school district wants us to check off boxes: I am supposed to demand that regular assignments be turned in; I am supposed to use Google Classroom to post weekly assignments; I am supposed to use the Remind app to message students about their assignments and my office hours. The assignments must be “aligning to priority standards.” For a school like mine, where 80 percent of students’ grades are based on proficiency assessments, this means that their learning must solely be about the Common Core standards if they want to earn class credit. The district allows teachers to choose the same standards they taught before school closed to count toward proficiency grades, but this assumes that teachers will be able to use these online pandemic months to help students who were previously behind to catch up.

Yes, the new “normal” results in a Pass-Incomplete system instead of a letter grade, with a nod toward equity during the pandemic. However, the district still requires us to make students keep working for their classes, with the assumption that — somehow — if students work hard enough, they can all meet these expectations. Teachers keep hearing that this is the “new normal.” But is this “normal” equitable? Does it make our students feel loved during a pandemic, when some are harmed so much more than others?

This doesn’t work for me as a teacher. I want to be authentic and loving to my students. I have written postcards to every one of them and wonder whether they received them. I cringe at the impersonal feeling of sending messages over Remind app. I also have two of my own children in my high school, and I know that families are flooded with regular messages and emails from multiple teachers. We are not teaching our students how to care for themselves, how to wrap their arms around their own families and community. Instead, as we push assignments out, we reinforce the value of productivity. I’ve been closing all of my emails to students with “Take good care of yourself first.” But then I contradict this message when I tell them I’m posting work weekly and that they need to demonstrate “proficiency” in order to pass this year. It keeps me up at night. My migraines tell me that I’m strained. And the sadness in my heart says this is all wrong.

Teachers keep hearing that this is the “new normal.” But is this “normal” equitable? Does it make our students feel loved during a pandemic, when some are harmed so much more than others?

As a parent and a teacher, I’m asked to do double duty as I shelter in place with four school-aged children. My elementary kids get two hours of homework a day from their Japanese immersion school. My 1st grader is too small to even know how to use a Chromebook, let alone navigate through the online programs he’s supposed to work with. Their classes meet at 9 a.m. twice a week as teachers strive to maintain “normal routine.” That’s eight classes a week for my children in the house, in addition to the weekly homework they need to complete and post. Meanwhile, my high school-aged kids try to navigate emotional health, with a grieving daughter heartbroken for her lost senior year and the school community she grew up with, while trying to navigate college decisions — without the closure of childhood and neighborhood. What I want and need for my kids are not being met by the demands of my school district, nor is my moral requirement to be authentic in both arenas, as teacher and parent.

These are not normal times — not for any of us — especially not for our children. We need to stop acting like they are.

If we think of this moment as making a post-COVID world in education, we need to be more defiant. We need to act in solidarity with kids. We need to call on all school districts to live up to their pronouncements about equity and justice. If what we are building for now is a more just world when we come out of this pandemic, then we must create a more just educational system starting now. Teen Vogue proposed a universal pass system where all students are given the same passing grade to prevent stigma for those inequitably harmed during this pandemic. In 1966, the scholar and activist Howard Zinn announced he would keep two sets of grades, his own and one to send administrators with all A’s, to prevent his institution, Boston University, from giving his grades to the Selective Service System, to determine his students’ draft status. Zinn said that he would not allow grades to play a role in helping the United States wage immoral wars. When the anti-racist educator Enid Lee came to Portland for the Northwest Teaching for Social Justice Conference a few years ago, she reminded us that although there is so much injustice in the outside world, we as teachers can stop that from entering our classrooms by showing what a more just world can look like. We can’t create a new normal by using the same tools as the old normal that were rooted in inequity and racism.

My student Erika, a junior in my Ethnic Studies class, captured her current herstory in a “What If” poem. She wrote:

What if I had the same privilege as you

If we weren’t taken advantage of for our labor

If we didn’t have to find a job that paid under the table

What if we were all equal

If I didn’t have constant fear

If my people didn’t work so hard for the simplest things

What if?

What if all teachers across the country joined together to rethink the way we’re loving our students? What if that time is right now?