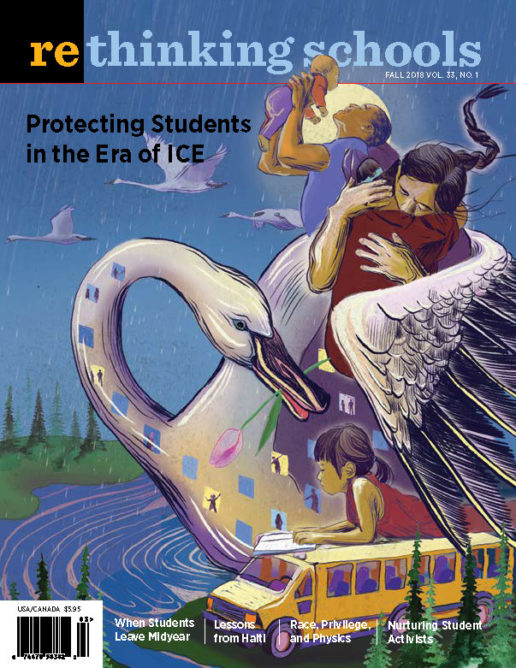

Shock-Doctrine Schooling in Haiti

Neoliberalism off the Richter scale

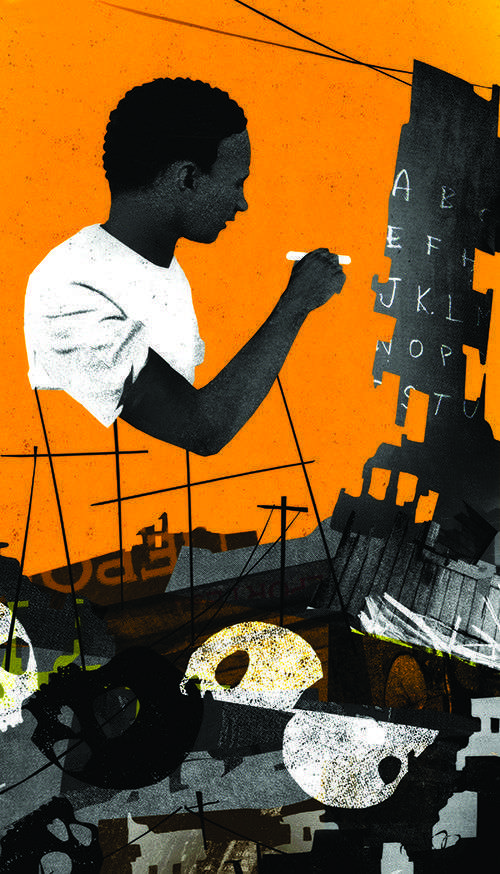

Illustrator: Brian Stauffer

Two days before the 2010 earthquake devastated Haiti, my 1-year-old son and I accompanied my wife there for an HIV training course she was going to conduct. And two days after surviving the quake, we drove to the center of Port-au-Prince from the Pétion-Ville district, where we had been staying, and passed a school that had completely collapsed.

As we drove by, I remember successfully convincing myself that not one student or teacher had been struck by the chunks of drab-gray cinderblock that lay scattered in the courtyard. As a teacher, I could not stomach the image of being trapped with my students under the debris.

I had just spent the last two days wrapping dozens of children’s bloodied appendages with bed sheets. I had children die while I was working to stop the bleeding. I needed the peace of mind that the students in that school had lived.

When I returned to Seattle and reviewed the statistics — that the earthquake on Jan. 12 displaced 1.3 million people, and injured 300,000, with another estimated 300,000 dead — it seemed certain that my confidence in the well-being of that school community was just a delusional coping mechanism.

The Haitian government estimated at least 38,000 students and more than 1,300 teachers and other education personnel died in the earthquake. As UNICEF reported at the time, “80 percent of schools west of Port-au-Prince were destroyed or severely damaged in the earthquake, and 35 to 40 percent were destroyed in the southeast. This means that as many as 5,000 schools were destroyed and up to 2.9 million children here are being deprived of the right to education.”

Haiti’s Education Minister Joel Desrosiers Jean-Pierre declared “the total collapse of the Haitian education system.”

The buildings may have collapsed, but the truth, however, was that the seismic activity of free-market principles had shattered the education system in Haiti long before Jan. 12, 2010.

In 2010, some 90 percent of schools in Haiti were private schools, and according to U.N. statistics, primary school tuition often represented 40 percent of a poor family’s income — forcing parents to make the unthinkable decision about which of their children they would send to school. Only about two-thirds of Haiti’s kids were enrolled in primary school before the earthquake, and less than a third reached 6th grade. Secondary schools enrolled only one in five eligible-age children, which is one reason why the illiteracy rate in Haiti was more than half in 2010 — 57.24 percent. Poverty and lack of access to education has led to desperate parents sending their children to work for host households as domestic servants. This has become known as the restavzék system, with an estimated 225,000 Haitian youth living in a state of bondage.

For most people, Haiti’s broken school system — which was literally buried under tons of rubble — is an incomprehensible horror. But for a few, the rubble looked more like building blocks, and the earthquake created a big break for business.

Meet Paul Vallas

Paul Vallas was the former CEO of the Chicago and Philadelphia public school systems and was hired in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina as superintendent of the Recovery School District of Louisiana that oversaw the transformation of the New Orleans school system.

Vallas’ legacy in these cities of privatizing schools, reducing public accountability, and undermining unions, made him a shoo-in to take charge of the Inter-American Development Bank’s (IDB) education initiative in Haiti.

“There’s a real opportunity here, I can taste it. That is why I’ve flown [to Haiti] so many times,” Vallas said.

The comment was clearly cribbed from former U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan, who indirectly praised Vallas’ work in New Orleans, saying, “I think the best thing that happened to the education system in New Orleans was Hurricane Katrina.”

Duncan justified his statement by arguing that the destruction of the storm allowed education reformers to start from scratch and rebuild the school system better than before. However, as Naomi Klein, author of The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism, pointed out:

The auctioning off of New Orleans’ school system took place with military speed and precision. Within 19 months, with most of the city’s poor residents still in exile, New Orleans’ public school system had been almost completely replaced by privately run charter schools. . . . New Orleans teachers used to be represented by a strong union; now, the union’s contract had been shredded and its 4,700 members had all been fired.

It should be apparent, then, that with Vallas at the helm of redesigning the Haitian school system, no child would be safe from an off-the-Richter-scale neoliberal quake.

Vallas’ scheme for Haitian education centered on maintaining a system in which 90 percent of schools are private, with the one modification: that the Haitian government finance these private schools based on the charter school model Vallas delivered to New Orleans.

The IDB’s then-proposed five-year, $4.2 billion plan for the remaking of the Haitian education system might best be described as the “Trojan school”: Using the promise of the day when there is reduced tuition in the bulk of Haitian schools as a means to permanently enshrine a private schooling system subsidized by the government.

The disregard for creating a quality school system in Haiti could not have been shown more forcefully than with Isabel Macdonald and Isabeau Doucet’s investigative report in The Nation on the Clinton Foundation’s first project in Haiti, a reconstruction effort in the city of Logne.

The reporters discovered that the Clinton Foundation provided Logne with trailers from Clayton Homes — the very company sued in the United States for providing the Federal Emergency Management Agency with formaldehyde-tainted trailers following Hurricane Katrina.

As Macdonald and Doucet reported, the trailers were to be used as classrooms — but they incubated mold rather than scholarship and were plagued with disturbing levels of formaldehyde:

As Judith Seide, a student in Lubert’s 6th-grade class, explained to The Nation, she and her classmates regularly suffer from painful headaches in their new Clinton Foundation classroom. Every day, she said, her “head hurts, and I feel it spinning and have to stop moving, otherwise I’d fall.” Her vision goes dark, as is the case with her classmate Judel, who sometimes can’t open his eyes because, said Seide, “he’s allergic to the heat.” Their teacher regularly relocates the class outside into the shade of the trailer because the swelter inside is insufferable. Two out of four of these classrooms provided by the Clinton Foundation couldn’t be used to the end of the school year due to temperatures frequently exceeding 100 degrees inside the trailers. As student Mondialie Cineas said, “The class gets so hot. The kids get headaches. And we go to the teacher for him to give us painkillers.”

As it turns out, Vallas has been a proponent — both in New Orleans and Haiti — of using trailers as classrooms, arguing, “There are ways to create a classroom learning environment that can be a superior learning environment, even if that classroom is in an inadequate building.”

When President Michel Martelly was elected in April of 2011, he made a promise to implement the IDB’s plan and the Program for Universal Free and Obligatory Education (Programme de Scolarisation Universelle Gratuite et Obligatoire — PSUGO) was established with the goal of educating “more than a million” students per year for five years.

In 2013, government banners around the capital declared “PSUGO — A victory for students!” But Haiti Grassroots Watch (HGW) conducted a two-month investigation in Port-au-Prince and Léogâne, revealing many problems with the education system.

“In addition to suspicions of corruption, the amount paid to the schools is clearly inadequate, the payments don’t arrive on time, and the professors are underpaid. Also, most of the schools visited by journalists had not received the promised manuals and school supplies, items crucial for assuring a minimally acceptable standard of education,” according to the HGW.

Teachers went on strike, and managed to win salary increases of 30 to 60 percent, but their salaries were already so paltry that the raises were inadequate. And as the Institute for Justice & Democracy in Haiti wrote, “PSUGO pays private schools six times the amount paid to public schools. This formula makes building a viable public school system virtually impossible.”

As was clear with the 2010 earthquake and the collapse of the school system — and with Vallas and other U.S. corporate reformers draining public resources — there can be no doubt that Haiti has many severe challenges, and there can also be no doubt that the cesspool of U.S. power, and of other dominant nations, are at the root of them.

That’s why for those who know their history, President Trump’s declaration that Haiti (along with El Salvador and other African nations) is a “shithole” country, was simultaneously both horrifying and absurd.

The urge to dominate Haiti dates back to its very founding in a mass slave revolt. In fact, the United States refused to recognize Haiti as a nation, from its independence in 1804 until 1862, because of the worry that the Black republic, run by former slaves, would send the wrong message to its own slave population. Then from 1915 to 1934, the United States enforced a violent and bloody military occupation on Haiti. As historian Mary Renda wrote, “By official U.S. estimates, more than 3,000 Haitians were killed during this period; a more thorough accounting reveals that the death toll may have reached 11,500.”

Since the 2010 earthquake, the United States and the international community’s record on Haiti reveals the same impulse to dominate rather than aid. As the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) Director Mark Weisbrot said in a January 2014 report, “The lasting legacy of the earthquake is the international community’s profound failure to set aside its own interests and respond to the most pressing needs of the Haitian people.”

Not much has changed in the years since then, as CEPR’s 2018 report reveals foreign aid to Haiti is still primarily being used to enrich U.S. corporations: Overall, just $48.6 million — or just over 2 percent — has gone directly to Haitian organizations or firms. Comparatively, more than $1.2 billion — or 56 percent — has gone to firms located in Washington, D.C., Maryland, or Virginia.

Even more horrifying is the fact that U.N. troops introduced cholera to post-earthquake Haiti by dumping the waste from their portable toilets into a tributary near their base. Instead of Haiti bringing a hot mess to other countries, as Trump would insinuate, it was literally a shithole from the world’s most powerful governments that was dumped on Haiti — and it resulted in a cholera epidemic that has killed more than 10,000 people and sickened another 1 million.

This is why Trump’s decision in 2018 to end the Temporary Protected Status for the Haitian refugees in the United States who fled after the earthquake isn’t only mean — it will actually be a death sentence for many. And far from Haiti being dependent on the United States, the balance ledger of history reveals Haiti has actually contributed far more financially and culturally to the United States. After the French lost the war to Black rebels and Haiti gained its independence, Napoleon Bonaparte was in need of some quick cash to continue his wars in Europe. So Napoleon struck a deal with the United States for 828,800 square miles of land — the Louisiana Purchase — for $219 million in today’s dollars. It was Haiti’s uprising and eventual defeat of Napoleon that led to the nearly doubling in size of the United States.

Moreover, the history and culture of Haiti and New Orleans are inextricably linked. As historian Carl A. Brasseaux has noted, “During a six-month period in 1809, approximately 10,000 refugees from Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti) arrived at New Orleans, doubling the Crescent City’s population. . . . The vast majority of these refugees established themselves permanently in the Crescent City. [They] had a profound impact upon New Orleans’ development. Refugees established the state’s first newspaper and introduced opera into the Crescent City. They also appear to have played a role in the development of Creole cuisine and the perpetuation of voodoo practices in the New Orleans area.”

But the nature of the relationship between these two cultures is currently being remade. The United States unmistakably exported its Hurricane Katrina response to Haiti and its schools — in a textbook case of Naomi Klein’s concept of the “shock doctrine” in which disaster capitalists seek to profit from calamity. A similar process is taking place in Puerto Rico, where the United States is taking advantage of the widespread destruction from Hurricane Maria to push a corporate education reform agenda of mass school closures, charter schools, and widespread privatization. On Oct. 26, 2017, about a month after Hurricane Maria first hit the mainland, Puerto Rico’s Secretary of Education Julia Keleher tweeted photos of school construction in New Orleans with the caption “Sharing info on Katrina as a point of reference; we should not underestimate the damage or the opportunity to create new, better schools.”

When the shock doctrine is applied to schooling, it has the effect of both profiteering off children and denying them access to the knowledge that could help them escape subjugation.

Governments the world over owe a debt to Haiti that is long past due — some from a history of direct colonial control or later economic subjugation, some from failing to honor pledges made in the aftermath of the earthquake, and some from failing to clean up the cholera epidemic that they introduced. If these debts were repaid, that would be the basis for constructing world-class education and health systems.

But with a white supremacist in the White House, it would be silly to wait for an apology, or for the proper type of funding to come through.

We need nothing less than a new Haitian revolution that connects with the movement for Black lives in the United States and brings down the structures of neoliberalism and of racism across the African diaspora.