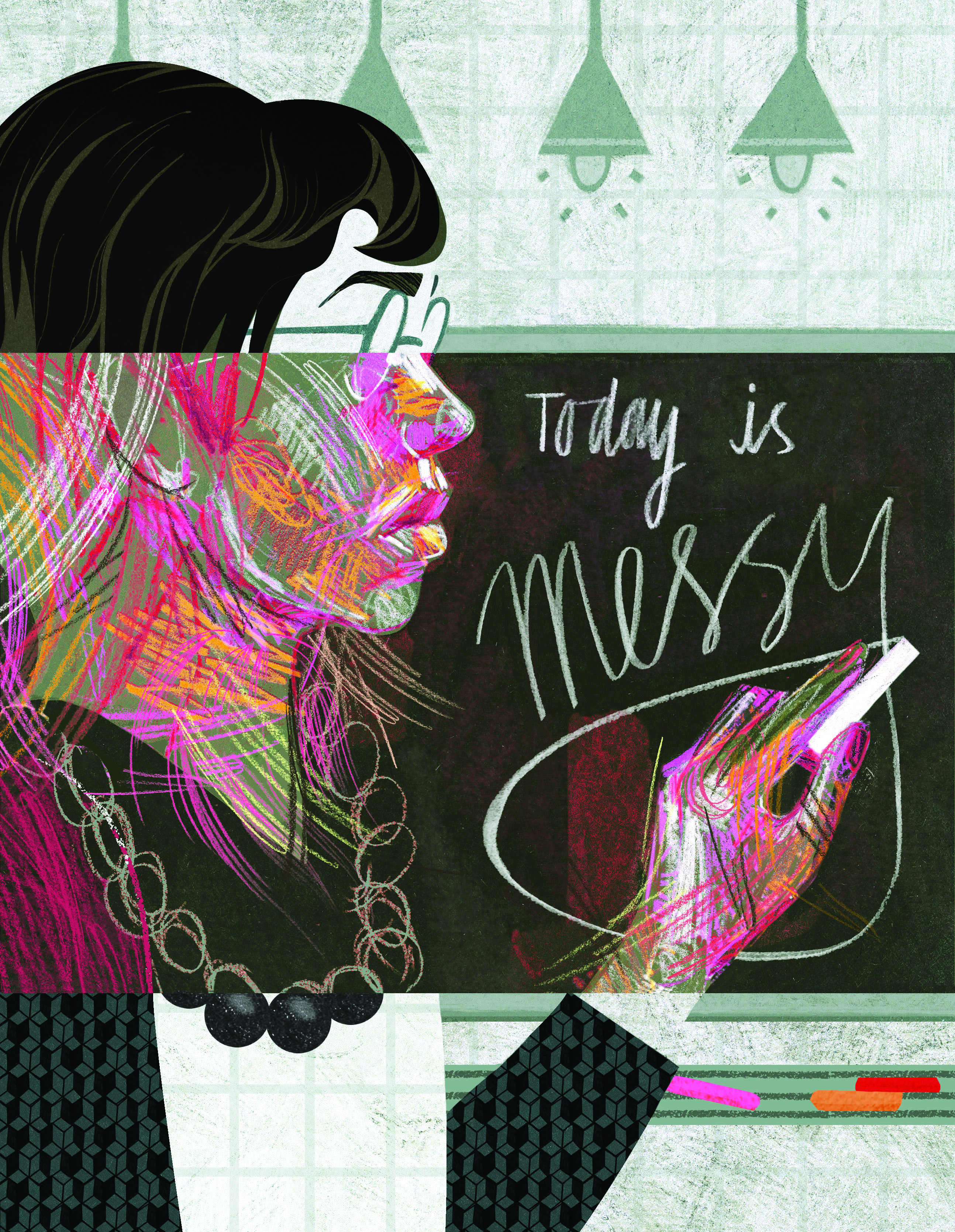

Sharing Our Real Selves

Illustrator: Adriana Vawdrey

I always wanted to be a teacher when I grew up because they were the adults in my life who most looked like they had their shit together.

They showed up at school each day, alert, well slept, with their coffee breath, neat clothes, prepared. I spent a lot of time as a kid imagining their lives outside of school. I imagined them waking up in clean, neat, cozy homes, waking up healthily early, drinking coffee, reading the paper, coming to school ready to teach.

How different that was from my own life, where adults slept all day in dark bedrooms or were gone. Waking up in a cold dirty house trying to find clean clothes to wear, amidst piles of garbage because the trash service had been cut off, sour milk in the fridge, hoping the neighbor was able to jump-start our car, my father screaming the whole way to school so that the first place I always had to go, before the attendance office to check in late, was the bathroom, where I’d wash off the mascara from my cheeks and run cold water over folded paper towels to make a compress for my red and swollen crying eyes. I could go check in once it looked like I hadn’t been crying anymore.

One of my favorite teachers in high school was my English teacher, Sam. He was fiery and a little weird and held high expectations for us. Sometimes he could be harsh but he was always real. I looked up to him not just as a teacher, but as a human being as well. I imagined his life was impossibly neat and tidy, bike rides on the weekend with his wife, clean house, reading books.

I don’t remember how it came up but one day he was telling us about his father. He told us his father was a raging alcoholic and years ago, when he was a young adult, he told his father he would talk to him again when he stopped drinking. He said it had been years and he still loved his father but he still drank so Sam still didn’t have a relationship with him. I was shocked. I had never heard a teacher talk about something like this before. This wasn’t a neat and tidy life. I realized I knew nothing really about the lives of my teachers, these adults who looked like they had their shit together.

I also realized this person with this mess in their life had made a life for himself on his terms. He cut off communication from his father so that he could keep himself healthy. I didn’t know people could do that. I had thought I’d be tied to my family forever. I learned a lot from Sam about reading critically, speaking up even when your opinion is unpopular, and writing a great essay, but the most important thing he taught me was that I could make a life on my own terms. That wasn’t part of any state standards, textbook, or written curriculum. I wonder what made him share that with us that day, and if he had any idea of the impact it had.

My first year student teaching I wondered about how much of my own life to share with students, trying to figure out what those boundaries are. Everything I was learning in my graduate program was telling me that to be professional meant to keep one’s personal life out of the classroom — not to bring in our opinions or politics or problems.

One day at lunch I was talking to a girl, Taylor, who lived with a foster family just down the street from me, with wonderful parents. She was crying.

“I’m so worried about my mom. Not my foster mom, my other mom. No one knows where she is. She’s using drugs again and she’s homeless, and no one knows where she is.”

I felt something inside me crack. My own mother had been evicted from her subsidized housing a year before. She moved two states away and had been in various forms of homelessness — living in tents and RVs, shelters, the streets. She was using drugs again and always lost the phones we sent her. We’d go months without hearing from her and I’d dread a phone call telling me she was hurt or dead. I hesitated. I knew what it felt like to feel so alone, to feel like no one else had problems like this, that no one else could relate. I didn’t want Taylor to feel alone, but I also didn’t want to jeopardize my relationship with her as her teacher. I decided to risk it, and decided to share enough so that Taylor would know what we had in common, but not so much that it would become about my experience and not her experience.

“I know how hard that is. My mom is homeless and I don’t know where she is either. I know,” I said. Taylor and I shared that moment. I couldn’t make her life easier, I couldn’t take the burden off her shoulders, I couldn’t go find her other mom, get her safe somewhere, and make her life neat and tidy. But I could be with her in that moment, and show Taylor that she wasn’t alone.

Teachers aren’t responsible for only teaching reading, writing, and math. Whether we mean to or not, we’re also showing them ways of being grown-up human beings. Many kids get a lot of good models for that at home. And some kids, like Taylor, like the kid I was, don’t. Those kids need us to show them what it’s like to make a life amidst the messy parts. They need us to show enough of ourselves so that they know they’re not alone.

I’m thoughtful about what and how much I do choose to share with my students. Ultimately I am their teacher, and whatever I’m sharing with them must have teaching behind it. It’s not teaching something in the state standards, but it’s also not sharing for the sake of sharing. It’s certainly not sharing for my sake, or for my understanding or my healing.

I had a professor once in college who managed to bring everything back to his recent, painful divorce. I didn’t learn a lot about philosophy from him, but I learned a lot about the bitterness in a man’s broken heart, and I don’t want to be that kind of teacher.

When I was in school, I didn’t know what kind of place there was for me in the world, and I needed people, like my English teacher Sam, to show me what a possible future might look like for myself. I needed people to normalize the kinds of challenges I was experiencing in my own life. That’s what I try to think about when I think about when and how and what to share about myself with my students. Who isn’t being seen? Who doesn’t see a place for themselves, or a future for themselves?

Sometimes it’s big and sometimes it’s the little, mundane details of life that my students need to hear. For the kids who live in apartments and feel out of place at the affluent school I teach at, I make sure that everyone knows I rent an apartment. On my first-day-of-school slideshow where I share generally about myself, I make sure to include pictures of some friends of mine who are a married lesbian couple. Around Mother’s Day, when one of my co-workers reminds our students to do something nice for their moms, I chime in to say that not everyone has a great relationship with their mom, or some people’s moms are dead, and there are so many other people in our lives who “mom” us. I let them know that some years I called my aunt or a friend on Mother’s Day.

Having your shit together doesn’t mean perfect, doesn’t mean impossibly neat and tidy, doesn’t mean it’s without complications, complexities, or stigmas, because having a healthy life isn’t about avoiding the messes Ñ it’s about how we deal with them. Our students need models of adults having messy lives, complicated lives, lives that don’t look like the stock photos that come inside picture frames. They need moments of communion as they work through their own adversities, and need to know that there is a possible future for them where things aren’t perfect, aren’t impossibly neat and tidy, but a future on their own terms, where they know they can handle what comes their way.