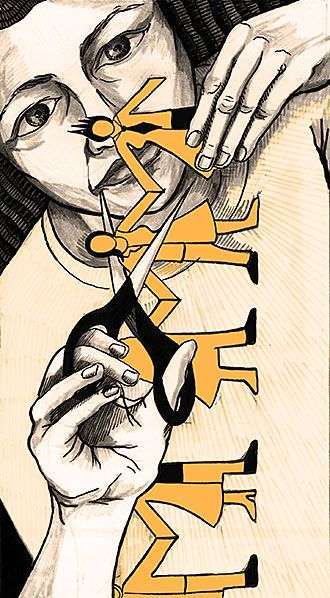

Sex Talk on the Carpet

Incorporating gender and sexuality into 5th-grade curriculum

Illustrator: Caroline Neumayer

My grade 5 students are gathered at the carpet area. I am dressed as a giant purple bell with a tinsel wig and sparkly Wizard of Oz shoes. There are cats and pirates and ghastly ghouls. It’s Halloween Day, and we are exploring the metacognitive power of asking questions while you read.

I read aloud from Christopher Phillips’ The Philosophers’ Club (a wonderful book for kids about how to ask big questions in a meaningful way) and we generate questions: Which came first, the chicken or the egg? What is philosophy? What is violence? These kids are fantastic at wondering about the world they are beginning to enter as pre-teenagers. Big ideas spark more questions and the kids call out all kinds of questions. I read: “Is it possible to be happy and sad at the same time?” and a voice asks, “Can you change from a boy to a girl?”

Maybe it’s the tinsel hair, the other worldliness of the day, but there aren’t gales of laughter. Suddenly my morning is a whole lot more interesting.

I could ignore the question, but it is a fair and important question, and deserves a fair and important response.

As teachers we make choices every day. What we leave in a lesson, what we take out. What we make time for, what we make disappear.

“Why, yes, a person can change from a boy to a girl, but it’s not like someone just wakes up one morning and says, ‘Hey, I think I’ll become a girl today.'”

Opening a Discussion About Transgender People

And so begins our discussion about transgender people. We begin to talk about what a serious decision that would be, how hard it must be to be in the wrong body, and how we hope that there would be people around who can accept you for who you really are. I have a good friend who first entered my life as a woman but who is now a man and very active in transgender politics. I mention that, if my friend was to come visit, the students would have no idea he had not always been a he.

We talk about how long the process can take. My friend didn’t make the decision overnight. Life as a teenager had been hell. He’d left home early, attempted suicide, and lived a pretty transient life. It wasn’t until he was in his late 20s and ended up in Vancouver that he finally made the transition.

Suddenly a small pirate in the group pipes up that she, too, knows someone who used to be a girl but is a boy now a family friend back in her home country of El Salvador. In still-hesitant English she explains that the biggest problem he had was his boobies, and that he had to bind them. What is most astonishing at this moment is that not one of my 9- and 10-year-olds giggles at the term “booby,” which under usual circumstances could have had them rolling on the floor. Instead they ask:

“What did he have to do?”

“Did it hurt?”

“Was it hard?”

“Did his friends still stay his friends?”

“What did his family say?”

“Can you tell?”

“Does he have a penis?”

“What about a beard?”

And what started as a language lesson became a life lesson.

Getting Comfortable Teaching About Sexuality and Gender

Could a discussion occur like this just out of the blue in any classroom? Certainly the question could but I would argue that the discussion might not. And that is a shame. It is a shame for the students in our classes who are questioning, trying to figure out who they are, and how they fit in this world. We need to open up the doors to talk about gender, sexuality, sexual identity, and acceptance of people for who they are.

But there are many barriers that get in the way: Fear that a parent will make a complaint. Fear that we are crossing some boundary of religious beliefs, fear that we don’t know all the answers, fear of straying from the plan for the day, fear of straying from the curriculum.

One reason I was able to lead this discussion was that a year earlier, a group of educators working with the Vancouver Board of Education developed teaching materials to address new curriculum learning outcomes around puberty. It’s called Growing Up: Teaching Sexual Health. When a flier advertised a two-day professional development for grade 5 teachers, I signed up. I was in the pilot group to test-drive the materials in my class.

It was an interesting year. I invited two volunteers from Options for Sexual Health (a nonprofit that was part of the curriculum planning process) to come work with me and my students. I jumped at the chance to have them help teach a section of the curriculum on reproductive body parts. During our time in small groups, a student asked how the penis and vagina meet. Tara, one of the volunteers, addressed it matter-of-factly and succinctly, and the group work continued.

The next day my principal approached me. A parent had called with concerns about what the “nurse” had told the kids the day before. I reported what had happened and reminisced about what I learned when I was in grade 5, growing up in Winnipeg. Or, more to the point, what I didn’t learn. In “sex ed” we heard how babies are made by the meeting of the egg and the sperm, and that once you got your period, you could get pregnant. Unfortunately, they left out that key detail how do these tiny little things meet in the first place? I am sure I was not the only little prairie girl confused about pregnancy and wondering if it happened from kissing, or a man touching you while you had your period, or what. My principal, a woman of a similar age and schooling, had similar memories. After we had a good chuckle about the ignorance of it all in our day, my principal agreed to respond to the mom. I was lucky. I had a supportive principal who believed in what I was doing with my students. More importantly, what was being taught was within the curriculum so there was no ambiguity about whether these kinds of discussions should occur. Here in British Columbia, parents can choose to have their children sit out these lessons, but they must provide a scheduled plan of how they will teach this aspect of the curriculum.

For me, it was significant that this student had gone home and talked about what he had learned that day, something that his mom lamented rarely happened. Yet the stigma surrounding talking about sex meant that this parent, who didn’t hesitate to ask me how to help her son in math or reading, could not cross the boundary to talk with me directly about this particular aspect of his learning.

Moving Past “the Nurse’s Puberty Talk”

Because I incorporated sexual health education into my weekly planning instead of inviting the nurse to come one fine spring day and have “the talk” with the girls while the boys have “the talk” with some brave male teacher on staff, my students developed confidence in asking questions about things they wanted to know or were fearful about. They also developed a healthy attitude toward talking about sexual issues in a whole class setting.

For example, a terms and definitions word sort of male and female body parts turned into a rigorous class activity. The school nurse had given me a good bit of advice: When doing activities with sensitive words or images, it’s helpful to have students working together on the floor. Maybe it’s the shift of focus from a screen or board, maybe it’s the ability to work closer together than tables or desks allow that eases the task, but it seemed to work. The students were divided into groups and given some time to match words with definitions. They settled right into the job at hand and no, they could not use the dictionary, they had to discuss and settle on their best guesses. In true grade 5 style, competitive spirit won out over any embarrassment about the words. I admit that I slipped over to close my classroom door, realizing that shouts of “clitoris . . . clitoris . . . clitoris . . . yes!” might be misinterpreted by an uninformed passerby.

Throughout that year, I made it clear that there were no girl-only or boy-only questions, that it’s important for each to understand what is happening to the other. I invited students to anonymously write down questions and deposit them in the Question Box; we went through them weekly. Mostly, at this age, the questions came from girls. There were the obvious ones like “How do babies get formed?” “Will it hurt to get your period?” “Is it OK to have periods when you are 10?” and then one that stood out: “Are movies on YouTube a good place to learn about puberty?”

What I learned from that year of piloting the curriculum was how much kids want to know and need to know. And how afraid both teachers and parents still are about talking about sex. Sadly, many teachers still leave the puberty talk to the nurses. If we, as educators, are not yet willing to have open and frank discussions about puberty and body changes and sex, how can kids ever begin to talk about sexuality?

And if the puberty talks only focus on procreation within heterosexual activity, what happens to our students who are already beginning to realize they might not fit that mold? If “family life” and sexuality are only presented within the confines of heterosexuality, if we do not open up our language to include the possible feelings of all of our students, by omission we are saying everything else is not normal. If students never hear the words gay, lesbian, transgender, and questioning from us when we are talking about sexual development, what message do we send?

So how did my class the following year end up ensconced in a serious discussion about gender in October? I hadn’t yet started up my formal, slotted health lessons. My letter to parents explaining my plans for teaching sexual education was still in draft mode on my computer. I was surprised we were in the midst of such an open conversation so early in the year, but I was prepared, too. The questions our students have are not compartmentalized into strictly math or social studies, science or health. Their questions come when they come. And my experiences from the previous year had left me confident and ready for this conversation. Maybe that’s why it happened.

Students of this age are hungry to learn new things. The days that “health” was integrated into the shape of the day were some of my best days of teaching. The conversations we had were honest and heartfelt. For many, these were things they weren’t likely to be talking about at home. And the “everydayness” of it meant that issues of gender and sexuality could arise at any possible moment in the day, like that Halloween morning in an ordinary language arts lesson.

This article is also available in Spanish.