Seeing Ourselves with Our Own Eyes

Illustrator: J. Leigh Garcia

“Maleeka,” he used to say, “you got to see yourself with your own eyes. That’s the only way you gonna know who you really are.”

—The Skin I’m In by Sharon Flake

In the lazy heat of summer, looking through next year’s class lists, the wisdom from Maleeka’s father chewed at the back of my mind. I teach special education to 6th, 7th, and 8th graders, and too often the deficit thinking required by the special education system — in which we document in thorough detail everything our students can’t do — makes students see their disabilities and themselves through a negative lens. How could I help my students start to see themselves through their own eyes?

I had stumbled across Trinidad Sanchez Jr.’s “Why Am I So Brown?” when I was in grad school, and it lingered in my heart. I loved the way the poem talked back to dominant culture and white supremacist ideas about skin color. I wanted to teach it to my students, but hadn’t been sure about when or how or where to bring it in. I eventually decided to use it at the beginning of the year as a mentor text for students to write poems about their own identities, to create their own “Why am I so . . . ?” poems.

This year, like most years at my school, my students were mostly white, though some were Asian, Latinx, and Black. In a time when “Black Lives Matter” is a phrase we can’t take for granted and in a school that is predominantly white, I wanted all my students to start the year with an explicit celebration of brown skin.

The students I work with all have individualized education programs (IEPs), and have academic goals in reading and writing. They have a variety of disabilities, including learning disabilities, autism, ADHD, and communication disorders. My students take most of their classes in grade-level general education classes, but take a literacy class with me to work on their reading and writing goals.

We read Sanchez’s poem on the first day of school. “Part of this poem is in Spanish. Do any of us speak Spanish?” I asked. “No? OK, then we will all do our best to read the Spanish lines.” We read through the poem together, taking turns to read each stanza:

A question Chicanitas some times ask

while others wonder: Why is the sky blue

or the grass so green?

Why am I so Brown?

God made you brown, mi’ja

color bronce — color of your raza

connecting you to your races,

your story/historia

as you begin moving towards your future.

God made you brown, mi’ja

color bronce, beautiful/strong,

reminding you of the goodness

de tu mama, de tus abuelas

y tus antepasados.

God made you brown, mi’ja

to wear as a crown for you are royalty —

a princess, la raza nueva,

the people of the sun.

It is the color of Chicana women —

leaders/madres of Chicano warriors

luchando por la paz y la dignidad

de la justicia de la nación, Aztlan!

God wants you to understand . . . brown

is not a color . . . it is:

a state of being a very human texture

alive and full of song, celebrating —

dancing to the new world

which is for everyone . . .

Finally, mi’ja

God made you brown

because it is one of HER favorite colors!

Initially, most of my class regarded the poem the way they might regard IKEA assembly instructions, with a mixture of confusion and wariness. I had underestimated the extent to which the Spanish parts of the poem would be daunting and formidable to them. After reading, we watched a video I found on YouTube that 7th- and 8th-grade Latinx students from the Seward Student Network in Chicago had made, with art and imagery to go along with their reading of the poem. I wanted my students to hear the poem read by Spanish speakers, and I wanted them to see the beautiful imagery the students in Chicago selected to go along with the poem, hoping this would illuminate some of the meaning for them.

We also spent time using Google translate to write translations of the Spanish lines. “So if Chicana is a ‘woman of Mexican descent’ and ‘itas’ means ‘something little,’ what would ‘Chicanitas’ mean?” I asked. Admittedly, our strategy of using Google translate failed us a bit here, as the meaning of the word “Chicana” is much richer and deeper than a “woman of Mexican descent,” coming from the work of civil rights activists in the Chicano Movement of the 1960s.

“Little women?” asked Haley.

“Girls! Girls of Mexican descent!” exclaimed Alec.

“What would a boy of Mexican descent be?” asked Elijah.

“Chicano is a man, so that would be Chicanito,” I replied.

“That’s me, I’m Chicanito,” Elijah grinned, rolling the word around in his mouth.

I asked students to share their favorite lines. “Because it is one of Her favorite colors!” said Mari, grinning a broad brace-filled smile.

“This is wrong,” said Ethan. “God is not a woman, it should say Him.”

“His god is a woman!” retorted Mari.

The students were intrigued with the subject of the poem. I asked them, “What was working in the poem?”

“That it’s in two languages, the English and the Spanish,” said Ariana. I was relieved that after spending time working through the Spanish they could see the beauty in the bilingualism.

“That it shows you can be proud of the color you have,” said Mari.

“It shows you shouldn’t be ashamed of what you look like,” said Ethan.

“I like how it’s one person asking a question and someone is responding, like dialogue,” said Alyssa.

I told them that eventually they would be writing their own poems. But while Sanchez starts his poem with a brief dedication, “for Raquel Guerrero,” positioning his words as a response to a question from someone else, I wanted my students to be both the questioner and the responder, to write a dialogue to themselves about themselves — self-affirmation as poetry. They started by brainstorming different things about themselves on the first pages of their workshop journals. “About me” we titled the lists. “All kinds of things,” I said. “Here’s my list — I’m white, I wear glasses, I’m fat —”

“You’re not fat!” said Ethan emphatically. “My mom says that’s a bad thing to say! You can’t say that about people.”

I usually have a conversation with students about my body at some point in the school year. I identify as fat — not overweight, obese, or plus size — and it’s important for me that my students see someone using fat in a positive, or at least neutral, way. I think that if fatness can start to be normalized for them, that if they can see fatness as part of the natural range of beautiful difference in humanity, that they may be able to see their own disability someday as part of the wonderful beautiful natural diversity of humanity. I hadn’t quite realized that by putting “fat” on my example list, I’d be launching into that conversation now, but I figured that one of the points of the lesson was for us to get to know each other, so we might as well start strong.

“I am fat, and I think it’s OK. I don’t mind being fat. I feel good about my body. To me, it’s just another way of being in the world. Some people are tall and some people are short, and some people have brown hair and some people have black hair or blonde hair, and some people are thin and some people are fat. My mom is fat and my dad is fat and my aunts and uncles are fat, and I come from a fat family, and I am OK with it. Not everyone is OK with it, and some people feel really bad about their bodies. For those people, calling them fat might hurt their feelings and upset them, so your mom is right, Ethan, you have to be careful how you use the word ‘fat.’ But I’m letting you know right now that I’m OK with the word fat, and you can call me fat, and I don’t think it’s a bad thing. What are all the things about you, maybe things that some people even think are bad? See how many things you can add to your list.”

I walked around, peeking at students’ lists. “Funny guy, Italian, brown hair,” wrote Alec.

“Male, shy, kinda quiet,” wrote Dylan, a student with autism who had hardly spoken in class last year.

We started by making metaphor banks, an idea I got from a workshop with the poet Denice Frohman. She said that when she writes with students, sometimes they start out by listing all sorts of colors, fabrics, food, and so on, so they have something to return to and look through as they’re trying to write. We listed fabrics, colors, and weather. We listed kitchen appliances, animals, plants, and musical instruments. “Can we please make lists of car manufacturers?” said Ethan, a student fascinated by cars. We listed all the different kinds of cars we could think of.

We returned to Sanchez’s poem and made lists about what we noticed about the style and content of his piece. I took notes for the class while students shared what they noticed.

“It starts with lots of questions,” noticed Kayla.

“And questions people wonder about,” said Elijah.

“Some parts repeat, like ÔGod made you . . .'” said Ariana.

“There are metaphors!” said Logan.

“He calls her ‘mi’ja‘,” said Elijah.

Then I showed them my “Why am I so?” poem, “Why am I so fat?”

A question chubby children sometimes ask

While others are wondering:

Why does the rain fall or

Why does the wind blow?

Why am I so fat?

The Universe made you fat, sweetie

Because it is the shape of your ancestors

Strong people made for hard work

And generation after generation of good cooks and good eaters

The Universe made you fat, sweetie

So your friends would always have a soft shoulder to lean on

Warm arms to hug them

A big heart to love them

And a big tummy to laugh big with them

The Universe made you fat, pumpkin

Because you are

A soft quilt full of down

A wrestler, ready to stand strong

A cumulus cloud, climbing up through the sky

A cello, wide with a deep and resonant sound

Finally, darling, the Universe made you fat

Because the shape of our world is round.

“What do you see that I did that was like what Sanchez did? What did I use from his poem?” I asked.

“You started with questions, too,” Kayla said.

“And you said what was good about being fat,” said Ariana.

“But you said, ‘The Universe’ instead of God,” said Logan.

“You said, ‘sweetie,’ sort of like how Sanchez kept calling the girl ‘mi’ja,'” noticed Elijah.

“Are you ready to pick a topic for your poem?” I asked them to return to their “About me” lists from the first day of school and to choose something that they wanted to write about. We had noticed that both my poem and Sanchez’s poem had described the positive things about that piece of our identity, so we generated lists about all the positive things about our topics.

We had also noticed metaphors used in both poems, and I encouraged students to go back to their metaphor banks to generate ideas. This was challenging for many of them. “I don’t know how to do this part,” said Alec.

“Well, what’s your topic?” I asked.

“Being obsessed with video games,” he said.

“OK, so if being obsessed with video games were a type of weather, what would it be?”

“Maybe a tornado?” he replied.

“Yeah, I love that image!” I said.

“I’m done!” exclaimed Ethan. He had written one thing on his list about things being good about being fast. “You get to places faster.”

“What else?” I asked.

“I don’t know anything else! That’s it! You get places faster!”

“What does it feel like to be fast?” I asked.

“It feels like you get a little breeze on your face when you run.”

“Yes, good! Write that down!” I answered.

Some students were ready to begin writing, and other students weren’t sure where to start. “Let’s look at the first part of Sanchez’s poem. If I were going to make it into a ‘fill in the blank’ for you to fill out, what might like that look like?” I asked. “Highlight the parts of the first stanza you would use in your poem,” I said. We then created a sentence frame together for the first stanza using what students had highlighted.

After students had a few days in class to work on them, we read our poems to each other. Seth, a boy with a huge heart who had been teased for being perceived to be feminine because of his emotional sensitivity, wrote about his empathy:

Why am I so empathetic?

A question some people ask

While other people are wondering

Why does the rain fall or what is the meaning of life?

Why am I empathetic?

You are empathetic, sweetie

Because you have a heart of a lion,

You want to see what other people see

You are empathetic, sweetie

Because you wish to sacrifice your time and your comfort zone

To help people in need

Finally, sweetheart, you are empathetic because you know that the world should

Have been filled with love and support and not with hate and suffering.

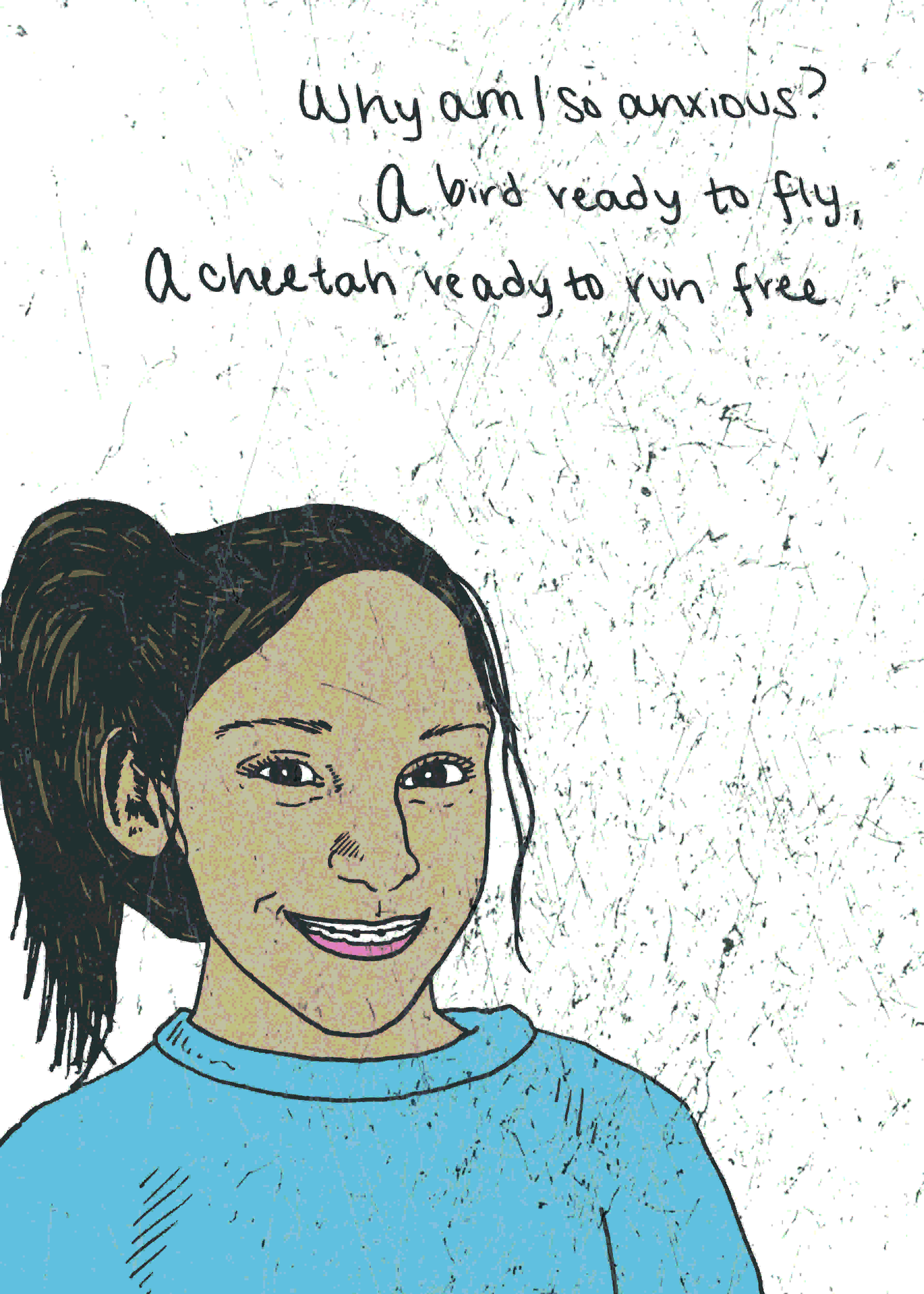

Savannah wrote about her experiences with anxiety:

A question some people may ask,

While others wonder,

Is why am I so anxious?

God made you anxious, precious,

Because you worry for them,

You are always there for them.

God made you anxious, precious,

Because you are like a puppy that just can’t wait.

God made you anxious, sweetheart,

Because others in your family have struggled with the same.

God made you anxious, sweetie,

Because you are

A bird ready to fly,

A cheetah ready to run free,

Finally, love, God made you anxious,

Because it strengthens you

every day.

I had been most concerned about my student Dylan with this writing assignment. Many of the more abstract pieces of reading and writing were challenging to him. Last year he had struggled to write metaphors about his name. His poem, about being quiet, blew me away:

Why I’m so quiet because god made you quiet

you like to listen or be a shadow.

Quiet like silent rocks and plants

Good thing about it is that you can concentrate on your stuff

I like that you like a spy swiftly quietly to a wall or the ceiling

Running to a hiding spot in a swoosh.

Finally, why I’m so quiet because it makes you silent.

Every student read their poem aloud to the class, and while we listened to each other we wrote down appreciations. Before our read-around, I modeled how we would give feedback to each other. “You’ll write down a compliment for everyone who reads. You could write down a golden line, or you could say something specific that you loved about the poem, or something the poem made you feel. You could write ‘I loved . . .’ or ‘I felt . . .’ And make sure to put who your compliment is to and who it’s from.” I wrote everyone’s name on the board so we would all make sure to spell each other’s names correctly. We were still getting to know each other, after all.

After our read-around, I told students to deliver their compliments to each other. They beamed as they read their compliments. “Everyone loved my line about orange like the sun, and orange like the mantle of the earth!” exclaimed Cassandra, smiling and sifting through compliments.

Months later, in December, I was helping a student, Chris, clean out his binder. “Not those,” he said, as I was sweeping through for old things to recycle. “Those are all my compliments, I’m keeping those,” he said.

So much of the time our school system takes away from students with disabilities, takes from them their “compliments,” their strengths and their value. Part of my job requires me to write long reports and plans that describe in quantifiable detail all the things my students can’t do, all the ways in which they don’t “measure up,” the ways they “don’t meet the benchmark,” while ignoring the ways their differences are beautiful and wonderful. Instead of seeing themselves through IEPs, evaluations, and test scores, my students have to be able to see themselves “through their own eyes,” and to talk back to systems that devalue them. Students with disabilities have to be able to hear the question “Why am I so . . . ?” and answer back boldly with love and truth. Students with disabilities have so much to offer not in spite of their disabilities but because of their disabilities. And if our education system can’t recognize it, we have to teach our students to recognize it themselves.

Katy Alexander (katy.m.alexander@gmail.com) is a special education teacher in Portland, Oregon.