Sacrifice Zones

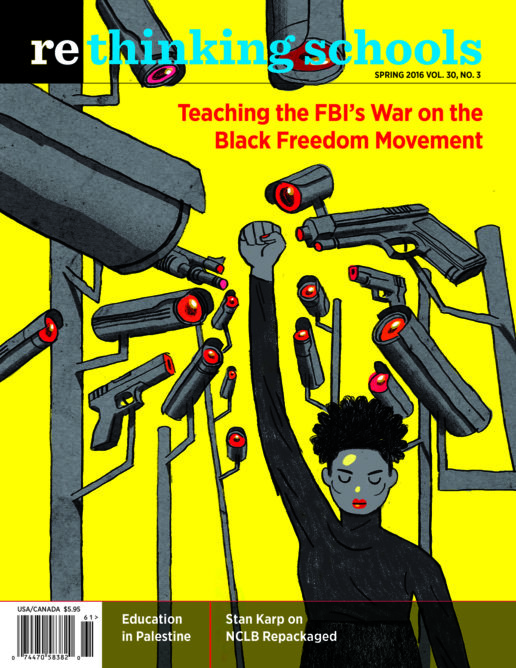

Illustrator: Erik Ruin

The concept of sacrifice is nothing new for my immigrant students. They have heard, seen, and lived the sacrifices their family members made coming to the United States. Some risked their lives crossing deserts and borders; others sailed through the Caribbean Sea and Atlantic Ocean in pitch-black containers. Most left loved ones and land in order to survive. Their parents may not have a shot at the “American Dream,” but they have all sacrificed tremendously to give their children a chance to make it. However, the idea that they or their parents may not really have had a choice in the sacrifices they made is new to many of my students, who escaped lands and economies made uninhabitable by capitalism and its hunger for fossil fuels and profits.

I teach 11th-grade English at an international high school in Brooklyn. My students come from more than 30 different countries and speak more than 15 languages. They are all English language learners and have been in the United States less than four years. Their diversity is stunning, but also a challenge. They come to my classroom with an array of literacy levels and academic skills in English and in their native languages. With a multicultural student body, it’s a struggle to find materials that address and respect their various homelands. I often search for ways to allow them to do their own research and share their knowledge with the rest of the class. In my eight years of teaching, I’ve learned Haitian history, eaten Bengali food, practiced my Dominican Spanish, and heard reflections on colonialism from Asia to Latin America.

Last fall, I started my English language support class exploring police brutality and the killings of Michael Brown and Eric Garner. My students were stunned that such racism happened in the United States and lacked the historical context to understand these events. Esther, one of my Haitian students, told me: “I’m scared of the cops in Brooklyn. I’m moving back to Haiti.”

I asked, “You don’t have racism in Haiti?”

“We discriminate more by what you wear and how much money you make.” She added: “You all are crazy here. I’m afraid to leave my house.”

I struggle teaching about race and racism in the United States for a couple of reasons. As a white woman, I need to be aware of my own privilege and respect the fact that my students may not always feel safe talking freely in front of me. And it’s a challenge to find that perfect balance between agitation and hope. Unfortunately, I tend to do better at agitating than instilling hope; perhaps that’s the inherent nature of the U.S. education system.

But I know how important it is for newcomers to learn enough about the history of racism in this country, particularly toward African Americans, to make sense of current events and the communities in which they are now living. I try to create contexts that help them make connections between that understanding and their own experiences as immigrants and in their home countries.

In December 2014, I participated in a curriculum writing retreat hosted by Rethinking Schools, the Zinn Education Project, and This Changes Everything. During the retreat we discussed, analyzed, and shared our teaching experiences through the lens of climate change and This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate, by Naomi Klein. During our discussions, I was struck by Klein’s concept of a “sacrifice zone.” Klein writes,

Running an economy on energy sources that release poisons as an unavoidable part of their extraction and refining has always required sacrifice zones—whole subsets of humanity categorized as less than fully human, which made their poisoning in the name of progress somehow acceptable.

For me, this concept is one of the big take-aways from her book. The idea of a sacrifice zone can be applied to many different situations and events, from Hurricane Katrina to the Keystone Pipeline to the impact of gentrification on our neighborhoods. There are groups of people who are treated as less than human and therefore disposable in the name of progress for “the greater humanity.” Well, who is the greater humanity? And who decides? Exploring these questions led me to think of more questions and their connections to my students’ lives: Who lives in these sacrifice zones? Who doesn’t? What is being sacrificed? Who benefits from the sacrifice? Often, when I have questions, I take them to my students. So, that’s what I did.

What Is a Sacrifice Zone?

I decided to engage students in the concept of sacrifice zones and try to apply this to what we had been studying and their own personal experiences. We had just explored the portrayals of Black people in the media, from the Detroit water wars to the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina to the testimony of Darren Wilson, the policeman who killed Michael Brown. We had a seminar discussion around these questions:

- Whose fault is poverty?

- Who’s to blame for public health crises?

- How are Black people shown in these images and stories?

- Is it different from how white people are being shown? How?

- What subliminal (undercover) messages are they teaching us?

- How does it affect the stereotypes we have about particular racial groups?

- What are the ways in which Black lives are disposable in these situations?

I gave students 10 minutes to reflect on one or two of the seminar questions. We sat at tables arranged in a rectangle, so everyone could make eye contact. At the beginning of the discussion, I explained: “This is how I sat in my college classes. I’m not going to call on you; we will do it popcorn style. Please be aware of your space. If you are speaking a lot, step back. If you haven’t spoken yet, step up.”

From the start, our discussion was drawn to the topic of white supremacy and its colonial roots. Students shared the images that the media creates of African Americans and their communities. Students used words like “dangerous,” “unsafe,” and “criminal” to describe the images painted by newscasters, movies, and video games.

Annie commented: “I was even taught in China, before I ever met a Black person, that Black communities were not safe.”

Aliya switched the conversation from media to resources and colonialism. She reflected: “Whites are taking resources from many communities and countries. It’s not just from Black people, whites are shown as superior over all races in the world.”

Samia, a student from Bangladesh, added: “There’s still colonialism today, it’s just called a different name. They take resources from Africa, like gold, and bring it to the United States.”

Jacques, from Haiti, said: “There are many divisions in my country, light skin versus dark skin, and village versus city. One group always has more power.”

At that point, I introduced the concept of a sacrifice zone to my students. I shared Naomi Klein’s definition and had the students read it a few times, annotate it, and discuss it. I wanted them to make this concept their own by constructing a collective definition that we all understood.

Students gravitated to the concept of sacrifice. Many of them deeply understand what it means to sacrifice something, so it was their first entry point to understanding.

“My family had to sacrifice a lot to come here. We had a huge house and lots of family in my old country. Now, we live in a small apartment by ourselves,” one student shared.

“Was it your family’s choice to move here?” I asked.

“Kind of. We wanted to have more opportunity than in Bangladesh.”

Another student added, “My mother won’t have the opportunity to go to college, but I will. Her life is sacrificed so that I can have more, and I bet my children will have more than me.”

The idea of a sacrifice zone was confusing to them. They understood making sacrifices, but they saw it as them or their family making a choice, not someone else sacrificing them for money and/or power.

“Yes,” I said. “You are all right about making sacrifices. But the way Naomi Klein uses the term sacrifice zone, it’s different. A sacrifice zone is when there is no choice in the sacrifice. Someone else is sacrificing people and their community or land without their permission.” They seemed to understand the distinction of a choice one makes as opposed to the choice that is made for you, but were still pulled toward the sacrifices they had made to be in the United States. The question of whether sacrifices are of free will is a larger question that warrants a deeper conversation. For example, Bangladesh is ground zero for climate disruption, so although my student’s family’s decision to leave may have been a personal choice, it was made within conditions over which the people of Bangladesh had no choice.

Another term they got stuck on was extraction. A few students in the class knew the term and defined it for us. “It’s when something is taken out of something,” Jacques explained.

I asked students to brainstorm different things that are taken from our communities. Here is our class list:

- Oil

- Gold

- Minerals

- People

- Music

- Dance

- Talent (sports and academic)

- Tourist areas (resorts, beaches, etc.)

- Workers

- Family members

Eventually, through sharing our ideas and talking through our confusion, we constructed this definition of sacrifice zones:

In the name of progress (economic development, education, religion, factories, technology) certain groups of people (called inferior) may need to be harmed or sacrificed in order for the other groups (the superior ones) to benefit.

I asked students to do some journal writing around these questions: Have you or someone you love lived in a sacrifice zone? What did they have to sacrifice? Did they have choice? Who did they sacrifice for? Who benefited from that sacrifice?

After journaling, students found examples from their own lives and families of sacrifice zones. They used their personal examples to fill out a chart with the following categories:

Name of sacrifice zone

Who lives there?

Who doesn’t?

What is being sacrificed?

Who benefits from the sacrifice?

What is gained?

When we came back together to discuss our charts, Karina described how the tourist industry is pushing people off of their land in the Dominican Republic. Dominicans are sacrificing their land in order for the government and the rich to make money building resorts. Now only foreigners get the opportunity to enjoy some of the D.R.’s most beautiful beaches.

Annie wrote: “In China, the pollution is making people live in a sacrifice zone, and the factories benefit from that.”

Samia wrote: “Some of my family members lived in West India, but in 1948 they had to move because of the war between Muslims and Hindus. I also know someone who was forced from their home so the government could build something there. This benefited the government, not my friend.”

Sacrifice Zone Poetry

The next day, we read a persona poem, “Jorge the Church Janitor Finally Quits,” by Martín Espada. I introduced the poem: “Today, we will read a poem from the voice and perspective of someone whose country, Honduras, became a sacrifice zone in many ways, and he was forced to leave.”

Students read the poem a few times out loud and then answered a few guiding questions in pairs: Who is the narrator? How does he feel? Why do you think he might have had to leave his country? How does that fit into our understanding of sacrifice zones? What happens to people whose countries or communities become sacrifice zones?

Excerpt from Jorge the Church Janitor Finally Quits

by Martín EspadaNo one asks

where I am from,

I must be

from the country of janitors,

I have always mopped this floor.

Honduras, you are a squatter’s camp

outside the city

of their understanding.

The students quickly identified the narrator as “an immigrant” and “a janitor.” Understanding the immigrant struggle intimately allowed them to easily connect with his feelings of loneliness and desire to be understood and known. One student wrote: “He feels like an outsider. He feels sad and disrespected.”

Another student wrote, “He sacrificed his identity, his country, and his name.”

Through discussing the questions in pairs and then as a whole group, the students revealed that they understood the feelings and perspective of the character. As one student said, “Through hearing Jorge’s voice we can feel his struggle, we connect with him.”

Throughout the year, these students had been writing plays in my English class with help from the Theatre Development Fund, so they were familiar with writing in first person. They also do well when prompted by a concrete structure. When I want them to write poetry, I provide a model poem that they can lean on for support. I told students, “Think about the feelings and needs of the people living in your sacrifice zones or any other sacrifice zones we have learned about this year. How do you want your reader to feel? What do you want them to know about the sacrifice?”

We started writing quietly in class. I wrote my own sacrifice zone poem while the students were writing theirs. Students always appreciate watching me doing the same tasks that I assign. We wrote silently for about 15 minutes. A few students shared lines from their poems at the end of class. Some students love sharing with the whole group, which offers inspiration to other students.

The next class period, I kicked off the sharing by reading my poem. Then, we did a go-around where students shared their poems and the inspiration for them. All students had to share at least a few lines from their poems. Some students’ poems were more developed than others, but they all enjoyed reading them and listening to each other’s work. For English language learners, poetry is often a great way to express themselves freely without being distracted by limited language.

Karina Garcia wrote about the Dominicans who were losing their land and beaches so the government and the rich could build resorts for non-Dominican tourists:

They want to get rid of us

They are painting this beautiful picture,

But not with us.

It is all a lie.We don’t want that place,

We want to stay here

With our beaches and trees.

No one knows all the things we had to sacrifice

This is our land andwe will fight for it.

Until the last day.

Samia Abedin wrote about the civil war in Bangladesh that made her grandfather leave his land.

I see the corpses that can’t be recognized.

I hear the cries of the families.

I smell the blood in the air.

Who is to blame?When has violence solved anything?

How did people become so cruel?

When will people embrace peace and equality?

When will this all stop?

A few weeks after the unit, two of my students read their poems at the New York Collective of Radical Educators conference. They shared their stories and their understanding of sacrifice zones in front of other teachers and their peers. At first, Samia was scared to read, but then she read her poem loud and proud. She even recorded a video, telling her sacrifice zone story and reading her poem, that co-presenter Alex Kelly, of the This Changes Everything Project, sent to Naomi Klein.

Overall, the activity was a success. By the end of the unit, all the students seemed to understand the concept of sacrifice zones, although the question of who has agency in these sacrifices still lingers. If I had more time, I would encourage students to do more research, to dig deeper into their examples of sacrifice zones and examine the social, political, and economic factors, especially in their native countries.

Today, far too many people live in countries and communities that are extreme sacrifice zones. And all of us are forced to make sacrifices every day: from budget cuts to civil liberties to our drinking water and the air we breathe. To varying extents, we live in overlapping sacrifice zones. Most of the time we are not asked or even told about the sacrifices coming our way. We are in crisis, and it is our responsibility to use this crisis to wake up our communities. It took the tragic death of nine beautiful Black people to remove the racist symbol of the Confederate flag from government buildings in South Carolina. What will it take to create a world where the lives of some people—especially the poor and people of color—are not sacrificed for the profits and luxuries of the rich?

Resources

- Espada, Martín. 2004. Alabanza: New and Selected Poems 1982-2002. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Klein, Naomi. 2014. This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate. Simon & Schuster.