Rocketship to Profits

Silicon Valley breeds corporate reformers with national reach

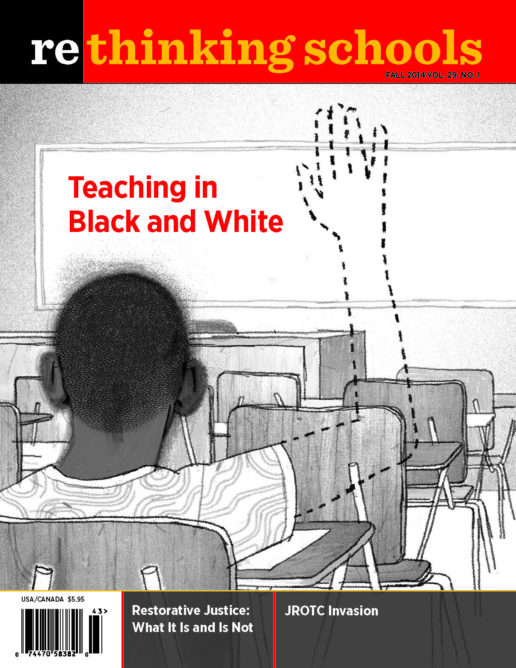

Illustrator: Ethan Heitner

Nearly every metropolitan area these days has its own wealthy promoters of education reform. Little Rock has the Waltons, Seattle has Bill and Melinda Gates, Newark has Mark Zuckerberg, and Buffalo has John Oishei, who made his millions selling windshield wipers.

Few areas, however, have as concentrated and active a group of wealthy reformers as California’s Silicon Valley. One of the country’s fastest-growing charter school operators, Rocketship Education, started here. A big reason for its stellar ascent is the support it gets from high tech’s deep pockets, and the political influence that money can buy.

Rocketship currently operates nine schools in San Jose, in the heart of Silicon Valley. It opened its first school in Milwaukee last year and one in Nashville, Tennessee, this fall. Its first two schools in Washington, D.C., where almost half the students already attend charters, open next year. Rocketship plans include running eight schools in Milwaukee, in Nashville, and in D.C. in the near future.

Rocketship also proposed a charter school in Morgan Hill, just south of San Jose. But there they ran into resistance from parents, teachers, and the teachers’ union. That successful campaign to block Rocketship and protect local public schools highlights the importance of confronting charter chains as they try to infiltrate school systems across the country.

“Blended Learning”

The Rocketship Model

“Blended learning,” the hallmark of the Rocketship education model, is based on using computers more and teachers less. Its roots lie in a valley dominated by high-tech factories, where electronic assembly lines belie the hype of entrepreneurship and “creative disruption.” Education policy analyst Diane Ravitch describes Rocketship charters as “schools for poor children. . . . In this bare-bones Model-T school, it appears that these children are being trained to work on an assembly line. There is no suggestion that they are challenged to think or question or wonder or create.”

A report by Gordon Lafer for the Economic Policy Institute, Do Poor Kids Deserve Lower Quality Education than Rich Kids? examined the Rocketship model: “The ‘blended learning’ model of education exemplified by the Rocketship chain of charter schools,” it found, “often promoted by charter boosters—is predicated on paying minimal attention to anything but math and literacy, and even those subjects are taught by inexperienced teachers carrying out data-driven lesson plans relentlessly focused on test preparation. But evidence from Wisconsin, the country, and the world shows that students receive a better education from experienced teachers offering a broad curriculum that emphasizes curiosity, creativity, and critical thinking, as well as getting the right answers on standardized tests.”

The contradiction between high-tech hype and regimented reality is a hallmark of the Silicon Valley model, and is not just found at Rocketship. “Blended learning” is promoted by John Fisher, who started the $25 million Silicon Schools Fund. Fisher is the son of Gap founders Don and Doris Fisher, among the world’s wealthiest clothing manufacturers and scions of San Francisco’s elite.

On the website of Navigator Schools, for example, a video promoting its Gilroy Prep charter (at the south end of Silicon Valley’s Santa Clara County) is full of superlatives like “incredible.” It claims its 1st and 2nd graders are “engaged 100 percent of the time.” Images show youngsters, each in an identical pale blue polo shirt with the Navigator logo, chanting in unison while a teacher holding an iPad moves through the classroom.

The slick video is just one indication of the big money at stake in the expansion of corporate charter schools in Silicon Valley. Students use “the best adaptive software,” the video enthuses. On their desks are “student responders,” remote controls with buttons for answering multiple-choice questions. “Gone are the days of textbooks and endless worksheets,” the narrator boasts.

The first goal of the Navigator mission statement is “to develop students who are proficient or advanced on the California state standards test.”

The use of computers in the Navigator video is a pale shadow of the dependence on them at Rocketship. In Education Week, Benjamin Herold (“New Model Underscores Rocketship’s Growing Pains”) explains: “For years, schools in the network have used the ‘station rotation’ model of blended learning, with students cycling each day between about six hours of traditional classroom time and two hours of computer-assisted instruction in ‘learning labs.’ That model . . . has allowed Rocketship to replace one credentialed teacher per grade with software and an hourly-wage aide, freeing up $500,000 yearly per school that can be redirected to other uses.”

According to Lafer, students in Milwaukee will take the state standardized test every eight weeks and the MAP three times a year. All their work in the learning lab is converted to data daily. Teachers’ salaries are primarily based on their students’ math and reading scores.

Education As a Profit Base

Rocketship’s tech connection starts at the top. Co-founder John Danner is on the board of a company that sells DreamBox Learning math education software. According to Lafer, venture capitalists John Doerr and Reed Hastings are primary investors in Dreambox and big donors to Rocketship; Hastings sits on the national advisory board. In turn, Rocketship uses DreamBox in its learning labs. “Thus,” Lafer concludes, “Hastings and Doerr help fund the nonprofit Rocketship chain, which contracts with a for-profit company they partially own; the more Rocketship expands, the greater DreamBox’s profits.”

Profits come other ways as well. Also according to Lafer: “Rocketship’s school buildings are owned by a sister company—Launchpad—which in turn charges Rocketship rent for the facilities. Rocketship’s official business plans include the goal that ‘Launchpad will charge relatively high facilities fees’ and that ‘the profit margin will be used to finance new facilities.'”

Hedge fund investors fund individual sites. One of them is former tennis star Andre Agassi. “Now it’s proven,” Agassi boasted to Bloomberg Business News. “Across the board, everybody is starting to realize that there is an innovative private sector solution.” His partner, Bobby Turner, adds, “If you want to cure—really cure—a problem in society, you need to come up with a sustainable solution, and that means making money.” Investors in the Turner-Agassi Charter School Facilities Fund include New York City’s Pershing Square Foundation. By summer’s end it will complete 39 schools for 17,500 students, growing eventually to 60 schools for 30,000.

Where do teachers fit into this picture? Rocketship’s charter application in Morgan Hill specified that its staffing ratio would go from 35.92 students per teacher in 2014-15 to 41.27 in 2016-17. Many teachers are hired from Teach For America, and noncredentialed paraprofessionals staff the learning lab.

“The student-teacher ratio at Rocketship schools is 27:1 during traditional classroom instruction,” Rocketship media contact Shayna Englin responded. “The learning lab is staffed by tutors and individualized learning specialists who receive extensive professional development and training for the months before the school year starts and participate in required hours of additional development weekly throughout the school year.”

However, a report by the Alum Rock, California, school district last spring said Rocketship was “misleading” when it didn’t include computer labs in its calculation of teacher-student ratios. They decided to reject Rocketship’s proposal.

Buying Politicians

There is a national trend toward corporate education reformers investing heavily in state and local campaigns—including city council and school board races. California is a scary example, with Silicon Valley money at the center.

In 2012, the Silicon Valley Community Foundation, run by the high-tech industry, formed an organization to promote charters, Innovate Public Schools. It got its first $750,000 from the Walton Foundation and $200,000 from Silicon Valley sponsors.

Innovate’s head is Matt Hammer, who for 10 years has been executive director of People Acting in Community Together (PACT). PACT has a history of supporting immigrant rights and a base in Catholic parishes. In the Silicon Valley area, however, it has also mobilized support for Rocketship and Navigator.

School reformers have spent heavily on local school board races. The Santa Clara County Schools Political Action Committee (created by the California Charter Schools Association) and Parents for Great Schools raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for the 2012 election—$40,000 from Fisher, $50,000 from Netflix founder Reed Hastings, and $10,000 from Rocketship board member Timothy Ranzetta, among others.

The PACs spent more than $250,000 to try to knock out Santa Clara County Board of Education member Anna Song, who survived nonetheless. They spent lavishly in East San Jose districts as well. Parents for Great Schools got $5,000 from Ranzetta and more from former San Jose Mayor Susan Hammer, PACT’s Matt Hammer, and Rocketship consultant Erik Schoennauer. “Had donors given money directly to support high-performing schools, they would have had a more beneficial impact,” Song told the San Jose Mercury News.

Silicon Valley capital is bent on playing a much larger political role. Former California State Assembly Speaker Fabian Nuñez is now a strategist for Students First, the reform lobby set up by Michele Rhee and headquartered in Sacramento. Nuñez used to be a California Teachers Association representative and assistant to the late Miguel Contreras, secretary of the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor. Nuñez shepherded $3.7 million to 105 candidates, including about $1 million to three Democratic candidates to the California Assembly, school board races in West Sacramento and Burbank, and $350,000 to the Coalition for School Reform, a political action committee that funneled money to candidates for the L.A. Unified school board.

This spring the industry’s titans ran a trade negotiator from the Clinton administration, Ro Khanna, against one of the most progressive members of the U.S. Congress, Mike Honda. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, Silicon Valley needed a voice for “those high-tech titans (Eric Schmidt of Google, Sheryl Sandberg of Facebook, Marissa Mayer of Yahoo among them)” and that the word among tech executives is “They just want more. They want—and this district deserves—a stronger voice in Washington.”

Vergara v. California: Buying a Judgment Against Teacher Tenure

The valley’s most far-reaching intervention took place this year—a successful legal attack on teacher tenure with chilling national implications. In 2012 David Welch, president of Infinera, a Silicon Valley fiber-optic communications corporation, set up another education reform advocacy group, Students Matter. He then filed a class action suit, representing nine children purportedly harmed by “ineffective teachers” to overturn teacher tenure in California. This past June, L.A. Superior Court Judge Rolf M. Treu ruled against teachers and in favor of Welch and the students in Vergara v. California.

Welch, whose company has revenue of more than half a billion dollars annually, gave half a million in seed money to Students Matter, and then lent it another million. The Broad Foundation and the Walton Family Foundation kicked in more. In 2012 alone, Students Matter spent more than $1.1 million on one of the state’s most powerful corporate law firms, Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, which fought the Vergara case.

In a Mercury News op-ed, Welch defended his attack on teacher tenure. “Experience is valuable,” he said, “but years on the job alone do not determine effectiveness. California law must explicitly prohibit the use of seniority as the primary basis for critical employment decisions.”

Diane Ravitch pointed out that at Rocketship “about 75 percent of the teachers are Teach For America, so we don’t expect to see many experienced teachers. . . . The founder of Rocketship is unalterably opposed to unions because, he says, they would limit his flexibility.” There is no union at David Welch’s Infinera, either, nor is there at any of the other high-tech firms active in promoting education reform.

“We believe the judge fell victim to the anti-union, anti-teacher rhetoric and one of America’s finest corporate law firms that set out to scapegoat teachers for the real problems that exist in public education,” Joshua Pechthalt, president of the California Federation of Teachers, told the Mercury News. “It’s discouraging when people who are incredibly wealthy, who can hire America’s top corporate law firms, can attempt to drive an education agenda devoid of support from parents and community.”

Judge Treu was greatly influenced by a controversial Silicon Valley figure, Eric Hanushek, who writes about education reform at the right-wing Hoover Institution at Stanford University. “U.S. achievement could reach that in Canada and Finland if we replaced with average teachers the least effective 8 to 12 percent of teachers, respectively,” he predicts, giving “astounding benefits, increasing the annual growth rate of the United States by 1 percent of GDP . . . over the lifetime of somebody born today . . . an increase in total U.S. economic output of $112 trillion.”

Hanushek sees firing teachers as the solution: “The previous estimates point clearly to the key imperative of eliminating the drag of the bottom teachers,” although he cautions it would be “politically challenging in a heavily unionized environment such as the one in place today.”

Hanushek testified before Treu, who then argued: “There is also no dispute that there are a significant number of grossly ineffective teachers currently active in California classrooms. Dr. Berliner, an expert called by state defendants, testified that 1 to 3 percent of teachers in California are grossly ineffective. Given that the evidence showed roughly 275,000 active teachers in this state, the extrapolated number of grossly ineffective teachers ranges from 2,750 to 8,250.”

David Berliner, the Regents’ Professor Emeritus of Education at Arizona State University, accused the judge of misquoting his testimony. “I never said that. I’m on record as saying I’ve visited hundreds of classrooms, and I’ve never seen a ‘grossly ineffective teacher.'”

Fighting Back

In Silicon Valley the commodification of education is proceeding rapidly. But the takeover of privatized education isn’t inevitable. This year the flashpoint was Morgan Hill, a rural town and increasingly a bedroom community at the southern end of Silicon Valley. About half the district’s 9,200 students are Latina/o. Last fall, both Rocketship and Navigator applied to the school district and then the county to open charter schools in Morgan Hill. Instead of a rubber stamp, they ran into massive resistance.

Theresa Sage, president of the Morgan Hill Federation of Teachers, AFT Local 2022, says, “In some schools, poverty is a big issue—the poverty rate is 23 percent in our district.” Morgan Hill schools only get $5,700 a year per student, one of the state’s lowest rates, and the legacy of Proposition 13, a measure passed in 1978 that limits property tax increases, is accentuated by the area’s poor rural past. “We have to address that, look at our own practice, and make a commitment to moving API scores [California’s ranked “academic performance index,” based almost entirely on standardized test scores]. That means working with the district and engaging our community. But a corporate takeover isn’t the right answer.”

The Morgan Hill district rejected the corporate charter petitions because of a strong mobilization by the union and other groups. “When the petitions were filed we had to act quickly,” Sage says. Concerned community members wrote a petition contesting the charters and supporting neighborhood schools, and posted it on MoveOn.org; it ultimately collected nearly 1,500 signatures. The petition explained that Rocketship’s plan would result in closing a neighborhood school and shifting large numbers of students and teachers to different school sites.

When the district rejected the two charter companies, they both appealed the decision to the Santa Clara County Board of Education. Morgan Hill teachers and parents packed the November meeting of the county board to speak out against the charter applications.

Then, in December, the union and the school district co-sponsored a speech by David Berliner, author of numerous articles analyzing high-stakes testing and the expert misquoted by the judge in the Vergara case. “He spoke about the effects of poverty on test scores,” Sage notes, “which is a big issue in our district. We absolutely believe we need to address the opportunity gap. And to do that we need to bring people together behind our public education system.”

A panel commenting on Berliner’s speech included Mario Banuelos, a board member of the Morgan Hill Community Foundation and a district parent, as well as two teachers, two administrators, and another community member. The sense of the meeting was a strong commitment to public education. In January 2014, the Santa Clara County Board of Education denied the petition by Navigator Schools to open an elementary school there. A week earlier, perhaps seeing which way the wind was blowing, Rocketship Education withdrew its appeal.

Sage charges that the charter wave seeks to exploit years of budget austerity. “We’ve had a cut of $22 million since 2008,” she explains. “So this charter push has come in at the peak of the impact of those lean years, and it’s been very aggressive.”

Nevertheless, in the classroom, according to mentor teacher Gemma Abels, teachers and the district are committed to carrying out the mission of public schools to provide a rich education, beyond teaching to the test. “We want our students to know how to use technology in life, art, and music,” she explains. “We’ve taken furlough days and even increased class sizes in order to keep programs so that kids have a wide range to choose from.” As a partially rural district, Morgan Hill still has a Future Farmers of America program, which today teaches high-tech agricultural science to a diverse student body.

In 2012, the union and the district initiated a dual Spanish/English immersion program, covering culture as well as language, for kindergarten through 2nd grade. Every year, as students progress, a new grade is added. There are two new focus academies—one for science, technology, engineering, art, and mathematics, and another for environmental science. Project Roadmap focuses on helping students who are their family’s first generation bound for college, while the district also increases the standards needed for graduation.

“Our teachers always say that test scores don’t truly measure a student’s progress, and that we don’t just teach to the test,” Abels explains. “I think we’re a progressive district, and pretty innovative.” She, like Sage, emphasizes the need to increase parent involvement. “Maybe this is one good thing to come out of this experience. It’s brought parents out to school board meetings and, if that continues, I hope we can engage people we don’t normally hear from.”