Heroes or Cultural Icons? Of Thee I Sing : A Letter to My Daughters

A critical review

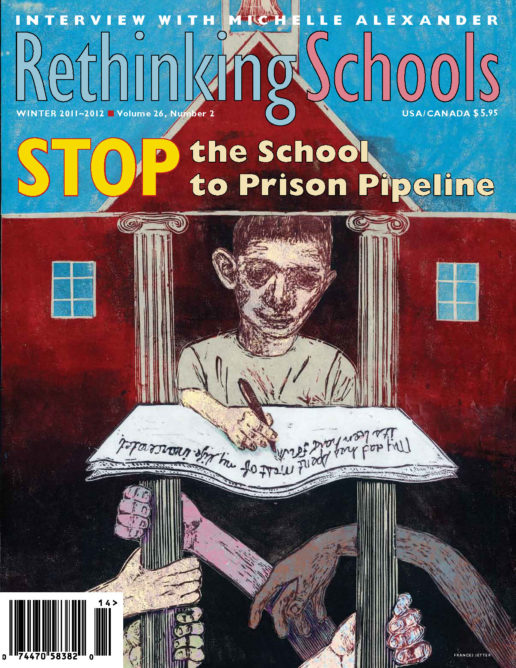

Illustrator: Loren Long | Knopf

Of Thee I Sing: A Letter to My Daughters

By Barack Obama Illustrated by Loren Long

(Knopf, 2010)

On the title page of President Barack Obama’s picture book, Of Thee I Sing: A Letter to My Daughters, the president’s young daughters, Malia and Sasha, are walking down a road as their papa looks on from a distance. The text begins:

Have I told you lately how wonderful you are?

How the sound of your feet running from afar brings dancing rhythms to my day?

How you laugh and sunshine spills into the room?

The left side of each two-page spread asks a question—“Have I told you that you are creative?” “Have I told you that you are brave?” “Have I told you that you have your own song?”—and shows the sisters approaching another child. The right side of each two-page spread identifies that child, pictures the individual as an adult, and explains the contributions to history. On the last page, father and daughters, hand in hand, continue their walk.

Much has been written about Of Thee I Sing, which the publisher’s copy describes as “a moving tribute to 13 groundbreaking Americans”—my guess is to memorialize the original 13 colonies—“and the ideals that have shaped our nation.” The book is a celebration of Obama’s young daughters and a celebration of “the characteristics that unite all Americans.” Much of the text is lyrical and moving. Many of the acrylic paintings, reminiscent of Thomas Hart Benton’s style in a glowing, subdued palette, are lovely.

But.

Many of the individuals chosen for this book are not seen by the majority society as “heroes,” as the jacket copy describes. Rather, they are more generally seen as cultural icons: Georgia O’Keeffe, Albert Einstein, Jackie Robinson, Billie Holiday, Helen Keller, Jane Addams, Maya Lin, Neil Armstrong, Abraham Lincoln, and George Washington.

To me, a hero advances social justice. A cultural icon, on the other hand, merely buttresses group mythology. For example, although many of us know that Helen Keller was a feminist, a socialist, and a courageous activist—who, in 1919, picketed the film of her own life in support of the striking Actors Equity Union—we were taught in school only that she was the blind and deaf child who learned to communicate and grew up to become a famous speaker and author. Unfortunately, it is Keller as a cultural icon rather than as a true hero who is portrayed and celebrated here: “Though she could not see or hear/she taught us to look at and listen to each other.”

Some of the individuals in the book are people I consider heroes: Sitting Bull, Martin Luther King Jr., and Cesar Chavez. But Of Thee I Sing’s central theme is the reinforcement of American mythology, so the portrayals of these individuals, too, are as icons. Although there’s a nod toward “multiculturalism,” with five women and six people of color, the book does not stray from the narrative of the mythology. Any references to struggles for equality, for human rights, for peace with justice, are couched in watered-down metaphorical language, with nothing that might prompt a child to ask questions. Martin Luther King Jr., for instance, “gave us a dream/that all races and creeds would walk hand in hand.” So then, the young child who is taught to be a literal thinker, rather than a critical thinker, might read the text, look at the accompanying painting, and surmise that King dreamed about holding hands with everybody.

Some of the text goes beyond metaphor to downright lie: “Our first president, George Washington,/believed in liberty and justice for all.” Excuse my rant: George Washington was a wealthy person who owned many Black human beings, a real estate speculator who stole land from the original inhabitants to sell to the new “Americans,” and an Indian killer whose forces rampaged through Mohawk and Seneca territories, pillaging and plundering, leaving only destroyed crops and burned villages. To many, he was a terrorist. In fact, the Mohawk and Seneca word for the title “U.S. president,” coined in Washington’s time, translates as “town destroyer.”

Abraham Lincoln, for politically expedient reasons, ordered the hanging of 38 Santee (Dakota) men after what has been called the Sioux Outbreak of 1862. This act remains listed in The Guinness Book of Records as the largest mass execution in U.S. history. And, as far as his sentiments about slavery, I quote from his letter to Horace Greeley in 1862: “My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.”

Sitting Bull as Landscape?

Then there’s the great Hunkpapa (Dakota) leader, Tatanka Iyotake (Sitting Bull). The right-wing media have had a field day objecting to his inclusion in this book. I doubt that he would have wanted to be referred to as a “great American,” but my big problem is with the text and painting.

Sitting Bull’s words are taken out of context and distorted to fit the book’s message. The text for that page reads:

Sitting Bull was a Sioux medicine man

who healed broken hearts and broken promises.

It is fine that we are different, he said.

“For peace, it is not necessary for

eagles to be crows.”

Though he was put in prison,

his spirit soared free on the plains, and his wisdom

touched the generations.

What Tatanka Iyotake actually said was this:

I am a red man. If the Great Spirit had desired me to be a white man he would have made me so in the first place. He put in your heart certain wishes and plans, in my heart he put other and different desires. Each man is good in his sight. It is not necessary for eagles to be crows. We are poor . . . but we are free. No white man controls our footsteps. If we must die . . . we die defending our rights.

A glossary entry notes that Sitting Bull was “most famous for his stunning victory in 1876 against Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer in the Battle of Little Bighorn.” Some media reviewers have painted Sitting Bull as a terrorist who killed Custer; others have insisted he wasn’t even at the battle. In fact, during the battle, which was indeed stunning, Tatanka Iyotake, a brilliant military strategist, worked behind the scenes, collaborating with the leaders on the battlefield—including Crazy Horse, Gall, Two Moons, Rain-in-the-Face, and Low Dog—any one of whom (or anyone else) could have killed Custer.

| SHORT LIST While my choice for a picture book about heroes would have been international in scope, here is my “shortlist”: Malcolm X, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King Jr., Septima Clark, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ella Baker, Bayard Rustin, Claudette Colvin, Leonard Peltier, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, Anna Mae Pictou Aquash, Roberta Blackgoat, Mary and Carrie Dann, Ellen Moves Camp, Gladys Bissonnette, Katherine Smith, Popé, Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta, Fred Korematsu, Yuri Kochiyama, John Brown, Rachel Corrie, Daniel Ellsberg, Joe Hill, and Mario Savio. Feel free to enlarge this list. Then do something heroic. |

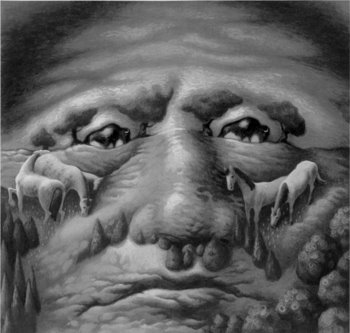

Then there’s the painting. Oh, that painting. Although all of the other people in the book are realistically depicted as human beings, Sitting Bull is a landscape. Literally. His eyes are buffalo. His eyebrows are trees. The bridge of his nose reflects the setting sun. Horses are grazing on his high cheekbones. And pine tree boogers are coming out of his nose and falling onto his upper lip. Interestingly enough, few reviewers have noticed this.

The unstated but obvious assumption is this: Indian people don’t even merit real faces; artfully constructing the face of a great Indian leader out of flora and fauna is a not-so-subtle way of implying that it’s still OK for Indians to be a backdrop for the Great European Adventure.

Tatanka Iyotake could have been portrayed as someone who made beautiful music. Sitting Bull was an accomplished flute player whose “meadowlark” song is recorded in several contemporary Native compilations. He could have been portrayed surrounded by children. Hunkpapa children adored Sitting Bull and followed him around the encampment. Poor children who were not Indian adored him as well; he often distributed money to them after Wild West Shows in which he was a paid performer. He could have been portrayed as a diplomat, consulting with Dakota, Arapaho, and Cheyenne leaders and negotiating with U.S. generals. He could have been portrayed as a man of courage, a military genius, an orator and a human rights leader who united tribes against U.S. military might. Instead, Sitting Bull is portrayed as a landscape and referred to as “a Sioux medicine man who healed broken hearts and broken promises.” Would that it were so. The “broken hearts and broken promises” still have not healed, even today.

Tatanka Iyotake did love his ancestral land, of course, but he wasn’t, literally or figuratively, “at one with the earth,” and he didn’t have pine tree boogers coming out of his nose. And what’s with the little boy (Sitting Bull as a youngster), wearing an eagle feather in his hair as part of everyday attire? That’s not done. Never was.

It’s my experience that children have the capacity to think critically and with great empathy; all they need are the tools and encouragement. I really wanted to like this book. It had great potential; that is why it’s such a disappointment. Sasha and Malia—and all of the children whose home is this place called “America”—deserve more.

P.S. A hero can be an ordinary person who has done extraordinary things, who selflessly acts for the greater good, who shows extraordinary courage in the face of adversity. Everyone has the capacity to be a hero, and most heroes go unrecognized anyway. Most of all, as Umberto Eco wrote: “The real hero is always a hero by mistake. He dreams of being an honest coward, like everybody else.” But this is an essay for another time.