Rethinking the Inclusive Classroom

Illustrator: Elliot Kukla

Part 1:

Making My Child’s District More Inclusive for Neurodiverse Students

by Melissa Winchell

Twelve years ago, my family’s small, suburban school district claimed to be fully inclusive for students with disabilities, a hopeful promise for us as new residents there. Finding an inclusive district was important to us; our teenage son had an intellectual disability and our baby daughter had been diagnosed with Down syndrome. But we soon discovered that the district had a strange idea about what “inclusive” meant; for them, inclusion meant that their schools had no substantially separate classrooms.

In truth, the district was not inclusive; it generated an excess of out of district placements for autism spectrum disorder and intellectually disabled/developmentally disabled students. Many of its neurodiverse students were being educated in nearby, larger districts or in collaborative programs. Although some of these out of district placements were justified, many of the placements would not have occurred, or could have been delayed, had there been districtwide inclusive programs and pedagogies.

As a former urban public school teacher, a professor of education at a state university, and co-founder of a nonprofit advocating with families with children with disabilities, I knew our district was not alone in its lack of awareness about inclusion. Too often, out of district placement becomes a perpetual cycle; because students are educated outside their district’s public schools, there isn’t a catalyst for a district’s mindsets and pedagogies to change.

I had dreams of inclusion for my daughter and for our district. But as my daughter progressed through the school district, I was confronted again and again by the medical model of disability — an incomplete belief that disability is a diagnosis of impairment. Some well-intentioned teachers hoped to use strategies to modify or correct what they understood to be her deficiencies. But approaching my daughter’s multiple disabilities as problems needing to be fixed or remediated proved ineffective and harmful.

Instead, my child thrived with teachers who understood her disabilities, which include Down syndrome, autism, anxiety, and ADHD, as opportunities to make their classrooms and schools more inclusive. For these teachers, my daughter was disabled not by her diagnoses, but by the many ways in which their schools, curriculum, and classrooms restricted her development. This social model of disability — in which disability is caused by the barriers that deny disabled students access to learning and a meaningful life — generates new ways of thinking about inclusion.

As special education directors came and went, I cheered along districtwide changes — like professional development for teachers on co-teaching, which holds promise for inclusive classrooms — and supported teachers as they piloted new pedagogies and practices. I offered advice as the district created a learning center program for classroom-based therapies and interventions. I served on search committees as our district hired its own therapists, like an occupational therapist and an adapted physical educator, and I connected the district with a professional developer who could offer inclusion training for secondary teachers.

My daughter is now 12. She is the first student with Down syndrome the district has educated, remaining in her hometown’s schools longer than we anticipated. Thanks to the progress the district has made since my family arrived, she is included in our district’s 6th grade and loves school. The best of her teachers have designed curricula centered on her interests — like baking — and collaborated with our family to presume her competence, remove barriers to her inclusion in after-school programs and school sports, and adapt their school schedules to her needs for rest and play. Together these teachers and I have found what we all know to be true about disability justice: When we make our schools accessible for one student, everyone benefits.

Understanding that the true disability is inaccessibility in schools, they seek to change their classrooms and not their students with disabilities.

In the next sections, two teachers in my daughter’s school district share their practices with including students with disabilities. With an understanding that the true disability is inaccessibility in schools, they seek to change their classrooms and not their students with disabilities. Their efforts are messy, incomplete, and ongoing; in other words, the slow and fraught efforts of social justice education.

Part 2:

Flexible Seating

by Karen Alves

During my first 10 years of teaching in an inclusive classroom I encountered one issue year after year after year — students who could not sit still. I started to wonder what would happen if they didn’t have to. Would they be more productive overall throughout the school day? Would they listen more? I was determined to find out.

So, I went to my then principal and explained my concerns to her. Lucky for me she was open to my new ideas and anything she could call a “pilot.” She asked me to come up with my exact plan. I set to work in early November designing my new classroom on paper — a high table that kids could stand at, a lower table where kids could kneel on pillows, bean bag chairs to provide some sensory movement, pillows and blankets tucked into a corner under a canopy for kids who felt more comfortable in a tight spot, couches for kids who needed to spread out. When I brought my design to my principal she approved it under one condition — the school would not help pay for any of the furniture. I agreed and we planned a start day for the day we came back from winter break.

My second step was to find the items I needed and to let the students and parents know what my plan was. I turned to Facebook to find suitable items. Within 24 hours of posting, parents in our predominantly white suburban town, as well as family and friends of mine, donated rugs, pillows, chairs, yoga balls, and more. Some bought brand-new items while others donated things in their homes they were willing to part with. I began to talk to my students and their parents about flexible seating and what it meant for our class. I even showed them a video of a class already using it. They seemed excited and I could not wait for winter break, when I could rid my room of desks.

As our holiday break approached, my excitement, although still alive and well, turned to concern. My concern was for Tommy. Tommy was autistic and suffered from anxiety. He had been doing really well in my class but seemed concerned about flexible seating. He asked lots of questions: “Where will I sit each day?” “Will other people be using my crayons?” “How will I know which books are mine?” I tried to answer these questions the best I could, but his worry did not seem to subside and his daily questions continued.

As a teacher of an inclusive classroom I am more than familiar with the old phrase “The best laid plans . . .” — lessons that end up being loud and scary for some students, moments when students just won’t do what’s planned, or days when we clearly didn’t see just how wrong an activity could go. But flexible seating had become my baby; I couldn’t give up on it just yet. So I went back to my drawings — back to the sofas and chairs and pillows and rugs — and right in the middle I added three desks, one with a nametag. And for the next three days I made sure to let Tommy know that the classroom was going to be changing, but his desk in the middle of the room would remain his spot. By the time break came I had (almost) convinced him that his spot would be there when he returned.

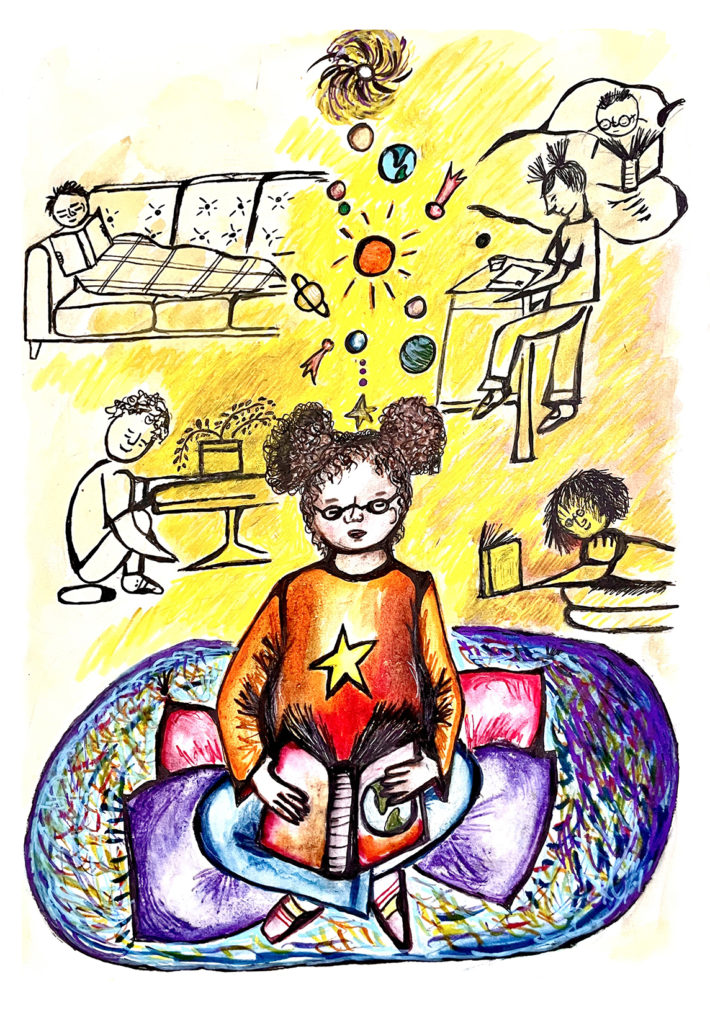

And it was. Our new room was full of all types of new items. Students used clipboards and could sit where they worked best. At first, of course, kids raced to the places that looked most fun. Eventually though, kids realized they didn’t work great on the couch because it was too squishy, or they liked to be on their stomach on the cold floor for testing. Students who had trouble sitting chose to stand at a table or kneel on pillows. My students were getting to know themselves as learners, at the ripe old age of 8.

Tommy came in every day and went to the desk with his name on it. Other students knew and understood that his desk was off-limits. But he was watching kids on sofas, on yoga balls, on pillows, or standing at a table, holding clipboards and sharing materials from the class bins. And after two weeks of watching, he joined. One morning I came into the room to find Tommy on a green yoga ball with a clipboard. My heart was overjoyed that he felt safe enough to try it. I smiled at him and he smiled back. Still grinning, he pointed to his desk in the middle of the room and said, “But that’s still my spot!” And it was.

Part 3:

Healing Circles

by Emily Messina

When I entered my second year of teaching, I was fearful of being a regular education teacher with many students with IEPs in my 1st-grade classroom. Although the year was full of many successful moments, it was also overwhelming. I was not used to spending so much of my planning time meeting with team members, reviewing behavioral and academic data, and attending IEP meetings. I felt like I was only scratching the surface of what I thought it would feel like to teach in an inclusive classroom.

In my mind I was spending too much time talking about students and not talking with my students. I allowed this frustration to help me rethink the way I used class time, and began spending more time building trusting relationships and incorporating social-emotional learning practices into my work with my students. I allocated time every week to activities centered around getting to know my students. My planning time was re-centered around creating materials based on individual interests, finding diverse stories to read, and participating in music, art, and other specialists’ classes alongside my students.

My students may be little, but that does not mean their emotions are. We spent many days and lessons practicing identifying our emotions, naming them, and determining what caused them. Eventually I implemented healing circles to create a safe place for students to express their feelings to peers, and for me to express my feelings to them.

A healing circle is where members of our classroom community sit together and share thoughts as a way to repair relationships. We use healing circles in my classroom whenever there is a behavior that causes harm to our relationships. This is something I first learned about through a classroom management program created by the Active Educator. When children have an outlet, they are more likely to understand their own feelings and have empathy toward others.

One afternoon Tyler was sharing a special moment with a friend. Tyler has autism and often had difficulty relating to peers and managing his big emotions. On this day, Tyler and Jake had a disagreement over which game to play at recess. Tyler became upset with Jake but was struggling to find a way to address it with him. He began to lash out, saying hurtful phrases and destroying Jake’s work. Tyler became so overwhelmed by the “fight with [his] best friend” that he began to engage in other disruptive behaviors that the team felt it necessary for him to take a break in our sensory room.

As things in the classroom settled back down, Jake asked if he could talk to me about what happened; he told me he didn’t understand why Tyler was being so mean to him. He recognized that Tyler had acted similarly in the past and knew that he often had difficulty with his big emotions, but Jake had never been involved with Tyler in this way. We discussed the situation and Jake had a better understanding of Tyler’s perspective. After our conversation Jake asked if he could lead a healing circle about what had occurred. Because this was still a very active situation for Tyler we held off on the circle until the following morning.

The next morning on the rug, I raised my hands to my heart (my favorite motion of a healing circle) and asked my class to follow along with me. I said, “Yesterday, a couple of classmates had a disagreement and it caused a break in a friendship. As you know, sometimes friends have a different way of handling their emotions. I saw many classmates showing courage when they saw these big emotions happening. When I looked around I saw friends working hard and respecting the privacy of our friends who were having a difficult moment.” I invited Jake up to continue the discussion. Jake began, “Tyler, yesterday we got upset because we didn’t want to play the same game. I am sorry that I hurt your feelings. Can we play together today?” It wasn’t often that Tyler wanted to be an active participant in a healing circle but when prompted by Jake, Tyler moved to the front of the room to stand near his friend Jake. I was surprised when Tyler offered his own apology and agreed to play at recess.

This was not only a great moment for Jake and Tyler, but also the other students to see how a healing circle helped facilitate a discussion to rebuild a friendship. Healing circles provide a space to develop empathy and compassion for others. They give students a chance to see that they are not alone in their feelings, and that our classroom is a safe place for them to learn and grow.

The social-emotional learning strategies I use benefit all students, but these practices have extra importance for students with disabilities. In my experience, when a student’s behavior goes unnoted, students often feel like it is bad or wrong. Part of ending the stigma is encouraging children to talk about what they see or notice. This was a big reason for a discussion I had with Tyler’s family at the start of the school year. His family was concerned about how others would respond to some of his reactions. The family noted that they found comfort in discussing Tyler’s disability openly with others (including school peers) because they felt it would improve his ability to interact with classmates in a more open and honest way. As the year went on students became more eager to help and understand Tyler; they were more accepting of his differences and more willing to spot the similarities.

I want students to feel like they have my support; at the same time, I want to gradually release responsibility for their emotional management back to them, over time. Another practice that has helped me do that has been calm bags. Every student in my room receives a personalized, soft pencil case — their calm bag — that they keep in their desk. Throughout the year we add calming tools to their bags that they can use at any moment in time. When I walk through my room of students, I find a calm jar sitting out on a desk, a puzzle being put together quietly, a breathing card being finger traced, a worry stone being rubbed, or a positive affirmation being read over and over.

I try to remember that every year is an opportunity to learn and grow. Not every healing circle is a perfect example of student encouragement and understanding. There are times that students are blunt or share details that have absolutely no relevance to the circle. And sometimes my students are too overwhelmed to use their calm bag. Helping students navigate their relationships with one another — big emotions and all — helps make my classroom a more inclusive place for students of all abilities.

Part 4:

The Hallmark of Inclusive Teaching

by Melissa Winchell

Despite the progress our district has made, this will be our child’s last year in our district. The truth is, inclusion as a paradigm shift and a practice has not yet reached every classroom and every teacher; our child has moved through her grade levels at a faster pace than progress. For example, our district persists in designating particular classrooms of each grade as “inclusion classrooms,” rather than insisting that every classroom include them. As such, these classrooms are an ironic misnomer for parents like me — they segregate our disabled children. I know our district is not the only one that does this; grouping students who need additional educators and support is a cost-saving measure. Too many classrooms persist in ableist paradigms and pedagogies and special education remains a siloed program that segregates a district’s most vulnerable students.

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) is nearly 50 years old. And although it guarantees a public education to our disabled students, so many of its promises remain unrealized. Worse, the inclusive vision of IDEA is increasingly under attack, as right-wing politicians criticize the kinds of social-emotional learning — including Emily’s healing circles and Karen’s flexible seating — that allow students with disabilities to thrive. But neurobiology and neuroscience are now confirming what inclusive teachers like Karen and Emily have long known: If we want academic success in our schools, we have to first design our classrooms for emotional resilience and health. I see real hope for inclusive, neurodiverse schools in these kinds of flexible, social-emotional pedagogies.

Without teachers like these, my child would not be the reader, writer, and mathematician she is today. Thanks to their efforts, she loves the solar system, uses a microscope, follows a recipe, plays inclusive basketball for her school team, tells her teachers what she needs, and names her emotions.

Karen and Emily, and inclusive teachers like them, demonstrate the hallmark of the most inclusive teachers my child has had in our district: pedagogical risk-taking. As a parent I can attest that not all of the strategies or ideas my daughter’s teachers tried were successful. But the most inclusive of these teachers persisted. If a strategy they tried didn’t work, they did some rethinking, collaborated with their colleagues, reached out to our family for input, and tried again. They know what a messy worthwhile struggle inclusive education can be.

They believe kids like mine are worth every effort.