Preview of Article:

Rethinking Thanksgiving: Myths and Misgivings

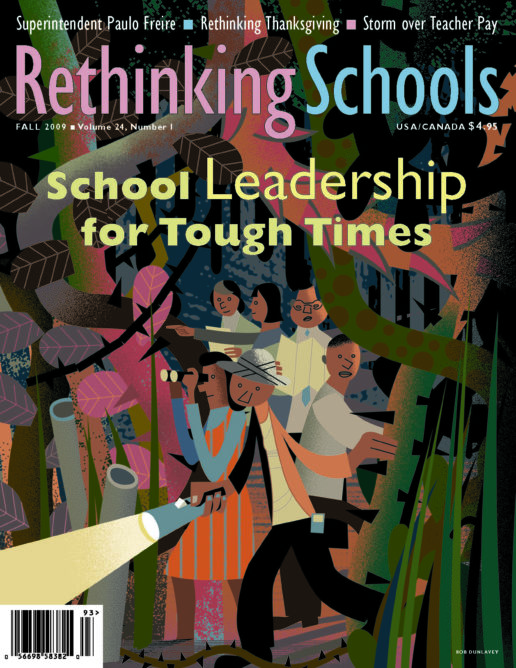

Illustrator: Eric Hanson

In 2006, an Atlanta newspaper ran several photos with captions describing the celebration of the Thanksgiving holiday. The first picture featured a 5-year-old girl wearing a precision-cut fringe vest made out of a brown paper bag from a local grocery store (as identified by the store name and tagline detailed prominently in big blue letters on the vest). On top of her head sat a multicolored feather headdress made of construction paper. The caption under the picture read: “Feathers in her cap. Ava adjusts the headdress of her American Indian costume for a Clairemont Elementary School Thanksgiving feast. More photos from the feast are on page J9.”

Page J9 includes three additional pictures—one showing a group of Pilgrims (with white paper collars and hats) and Indians (as identified by their feather headdresses, of course). A second picture shows students in “costume” working on a coloring project and a third captures a student showing off his “homemade American Indian costume.” Between the pictures it reads: “Clairemont Elementary School studied American Indians and Pilgrims in preparation for today’s big holiday. Last week, they re enacted the first Thanksgiving and dressed in costumes for a feast with family members.” In the center is the phrase “Thanks for the lessons.”

What lessons did they learn? Between Columbus Day in October and Thanksgiving in November, Native Americans [the “official” curricular name in Georgia] play a key role in the mythology of U.S. history as taught in schools. As someone who works with pre- and inservice elementary teachers, I see firsthand how these happy stories maintain children’s ignorance and reinforce stereotypes.