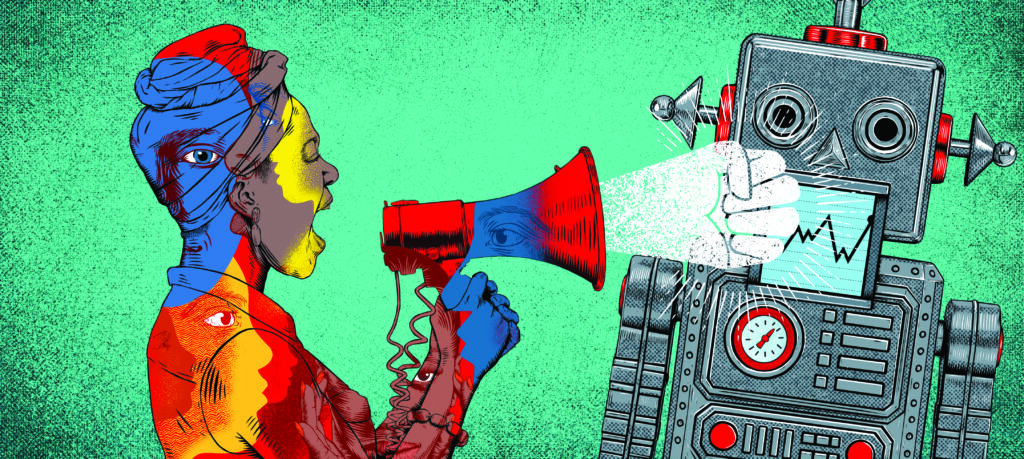

Resisting AI Mania in Schools

Illustrator: Boris Séméniako

When I applied for secondary teaching jobs after a corporate career, interviewers asked what I would bring from my experience. Some seemed disappointed I didn’t tout my facility with the Microsoft suite. Believing the business world was “light years ahead” technologically and that schools needed to “catch up,” they spoke excitedly of a new era in education about to be ushered in . . . by PowerPoint.

A quarter century later, many districts are being gripped by AI fever. Eager to seem on it, one near me just added a cute chatbot to its website.

The list of reasons to resist this latest edtech mania is long — from the practical to the philosophical, pedagogical to ecological, egalitarian, and ethical. Education trends and fads, especially tech-related, can be hard to resist however, even when they run counter to our ideals. Being alert then to messages meant to push or pull us into participating is important.

Below I discuss several of the most common messages educators receive encouraging us to embrace AI and why we should push back.

“AI will save you time!”

Curriculum purveyor Twinkl welcomes you to its “AI hub” with the following: “Empower yourself with our suite of AI-powered tools designed specifically for educators. Designed to save you valuable time so that you can use your energy and expertise where they’ll be most useful — with your students.”

Districts across the United States are encouraging teachers to use AI tools such as ChatGPT to create lesson plans or to provide instruction, differentiate, create assessments, grade work, and provide feedback to students, all in the interest of productivity.

The recent history of edtech suggests this benefit may well be a pipe dream. In a new study, David T. Marshall, Teanna Moore, and Timothy Pressley found that learning management systems (LMS) sold to schools over the past decade-plus as time-savers aren’t delivering on making teaching easier. Instead, they found this tech (e.g., Google Classroom, Canvas) is often burdensome and contributes to burnout. As one teacher put it, it “just adds layers to tasks.”

LMS were intended to alleviate the duller, bureaucratic, peripheral tasks of the job — at which they seem to have largely failed. These systems have also led to dehumanizing relationships between administrators and teachers and between teachers and students. Electronic open gradebooks have contributed to the increasingly transactional nature of education. (I hand in work, you pay me with a grade calculated to the second decimal.)

Now teachers are being prodded to use AI tools to — at least partially — replace some of the most intellectual, creative, core components of the profession. Teachers using ChatGPT to produce lesson plans have defended this to me by explaining how they read through to check and fix or flesh them out. OK, so how much time is saved? Indeed, it took software developers in an METR study who used AI tools 19 percent more time to do their work. Nevertheless, because they expected to save time, they believed their work had been sped up by 20 percent. This gap suggests self-reported time savings from AI are suspect.

Let’s assume for a moment that AI tools are eventually able to produce great lesson plans and great time savings for teachers. Teachers learn early in our careers that when work is taken off our plates, something else gets ladled onto it. So it’s easy to suspect that any time saved by AI tools will provide permission to add students to rosters and duties to schedules. It may also give permission to replace us entirely: Arizona just approved a virtual, AI-driven, teacher-free charter school. We’ll have plenty of time then.

“AI can personalize learning!”

Proponents of AI in education tout its ability to “personalize” learning, a familiar edtech marketing claim. They usually mean what educators call “differentiation,” structuring learning so students in a heterogeneous group can be reached where they are.

But personalization requires a person. And children deserve personal care. In The Last Human Job: The Work of Connecting in a Disconnected World, University of Virginia sociologist Allison Pugh reveals how the caring professions — from teaching to medicine and more — are being warped and degraded by the imposition of tech, including AI.

When the “connective labor” of these professions is intervened by or contracted out to tech, Pugh highlights, it is depersonalized. The “encouragement” provided by a bouncing avatar or a digital spray of fireworks is a mockery of the teacher-student relationship, which research has repeatedly proven to be among the most important factors in student engagement and academic success. Children need our human attention — especially in this age of social isolation and political trauma.

Boosters will counter that AI tools aren’t meant to replace teachers, just help them. And yet, from the other side of their mouths, many will say that more teachers and tutors would be best, but we simply can’t afford them. Which, of course, we can. The federal government spent just $119 billion on K–12 schools in 2022 and Trump & Co. is slashing that number by the day. Spending nationwide on K–12 edtech, meanwhile, is expected to grow to about $170 billion a year by 2030. These are choices.

When we don’t have sufficient tutors or smaller class sizes for all, that feeds arguments, Pugh says, that AI automation is “better than nothing.” The Last Human Job reveals the likely outcome of this kind of thinking given our systemic inequities: the haves receiving mental and physical health care, education, and other services from expert humans and the have-nots getting stuck with inadequate AI proxies.

AI then can be worse than nothing. “The aggregate of [our] small decisions,” Pugh argues, could lead to greater inequity, disconnection, dehumanization.

“You’re avoiding AI out of fear!”

A colleague once suggested I was afraid of change for questioning the value of a new program. Having by then changed careers twice, cities a dozen times, and boyfriends too often, I tried not to let it get under my skin. But teachers who announce they find a new curriculum, system, method, or protocol problematic can be told they’re afraid. This is very much happening with AI.

With this messaging, several -isms can come into play. Veteran teachers who resist AI can be made to feel like old dogs too tired or scared to learn new tricks. Teachers of color concerned about biases being built into AI tools by mostly white designers can be dismissed as overly fearful or as “making everything about race.”

And the three-quarters of teachers who are women are also susceptible to being painted as afraid of AI. The language in a recent Bloomberg article was telling:

If women are more risk-averse and fearful of technology, at least on average, and if an appetite and willingness to adopt new technology is a precondition of being able to thrive in a brave new labor market, generative AI could feasibly exacerbate the gender pay gap.

Hesitant attitudes toward AI here are “risk-averse” and “fearful” when they could be described as thoughtful, careful, or skeptical. Enthusiasm for AI is cast glowingly as an “appetite” and “willingness” when it could be gullibility, susceptibility to marketing, or disregard for costs and consequences.

In the end, this refrain is little more than an ad hominem attack — and an ironic one at that. It’s trying to scare someone by calling them scared.

“Using AI makes you a cutting-edge teacher!”

This is a counterpart to the fear argument. Just as no one enjoys being perceived as fearful and cowering, few want to feel out of touch — or as though they aren’t one of the cool kids in the know about where the party is. When I spoke to edtech expert, consultant, and former teacher Tom Mullaney, he explained that “FOMO (fear of missing out) rules everything” when it comes to AI in education.

This message rewards AI adopters by labeling them as cool, modern, forward-looking, cutting edge. The resisters by contrast are desperately clinging to the past — and maybe aren’t all that sharp.

Interestingly, however, a recent study revealed that the more people understand about AI, the less receptive they are to it. Dr. Damien P. Williams summarized it: “People not knowing how ‘AI’ works is what makes them open to using it, and . . . the more they learn about it, the less they want to use it.”

Just like the school leaders of 2001 who saw magic in Microsoft Office, some today see magic in AI — in part, this study demonstrated that those who understand it least may see it as the most fantastic in all senses of that word. This may be why many districts and schools are getting teachers to “play” with AI: They don’t know how it works or what it can do for education but they’re convinced it’s the future — and they want teachers to figure it out.

“You have to prepare your students for the future!”

This message packs a punch because it taps into teachers’ hopes and wishes for the children and young adults they teach and love. Then there’s the attendant guilt that can dog us, the feeling that we could always be doing more.

The World Economic Forum is one organization eager to push AI into schools because “[i]ntegrating AI into education, through traditional or innovative methods, is key to shaping tomorrow’s workforce.”

In high school I took a business elective where a lot of time was spent learning how to operate a keypunch machine. After college graduation, I went to work for an investment bank and consumer product companies, and as you can imagine, not one was interested in my ability to use a then obsolete data entry method.

Technological change today is even faster. Teachers of secondary computer science and librarians and teachers of certain disciplines at the college level may have good reasons to teach students what AI can and cannot do and might do. Humanities teachers may want students to research the topic and its economic, social, and ethical considerations.

But what pretty much all of us are being urged to do goes well beyond that. As Mullaney clapped back, in a thoughtful piece on his blog, we are “teachers, not time travelers.” He points to the absurdity of trying to revamp classes and schools for a rapidly evolving technology that may not meet its hype and may not look much like it does today when today’s students are working tomorrow. Why should schools spend scarce resources retooling curriculum and instruction for a future we cannot know?

“Students are already using AI and it’s here to stay, so you must teach them how to use it ethically!”

This is the biggie, based on a sense of inevitability. AI is an inexorable Zamboni that will resurface the ice with you unless you grab onto the back and ride.

Is it my responsibility as an English teacher to teach students how to use AI? I already have a basketful of responsibilities — and AI is working against them. My core mission includes teaching students how to (actually) read and (actually) think about and discuss what they read; to (actually) analyze rhetoric and literature; to (actually) conduct (their own) research; and to express (their original) thoughts in writing.

A rising number of students are already using tools such as ChatGPT to replace their own reading, thinking, research, and writing — and often with crap. Just one example: A student “produced” for me a literary essay that was not only stiffly written and illogical but included quotes from a text other than the novel being analyzed — which the student didn’t realize because they avoided reading the book, thinking about it, finding evidence from it, and constructing an argument by going straight to ChatGPT.

The bad news is that as these tools develop further, plagiarized work will likely get harder to catch. Imagining we can tame this new, evolving, many-headed beast of plagiarism by teaching students to use it well is folly. Cheating is an age-old problem that AI just makes much, much easier.

Furthermore, this “you can’t beat them, so you must join them” plea may sound familiar — because it’s what we heard about cell phones. Told it was our job to teach responsible phone use and even to integrate their use into classes, teachers were given an impossible job. A decade later, cell phone bans are sweeping the nation and more are recognizing the distractions of other devices being overused in classrooms.

There is one real clincher, though, on the ethics question, or there should be. “Teach them how to use it ethically” is a line that ignores the impact of AI on the planet our students will inherit from us. It must ignore this because — setting much else aside, including the industry’s abuses of copyright and of workers — AI’s health and environmental costs alone mean there may be no such thing as ethical AI use.

AI consumes huge amounts of water and energy and produces significant emissions, air pollution, and electronic waste. Given this, when schools and entire communities are burning in wildfires and being leveled by hurricanes and swamped by floods fueled by climate change, why on earth should teachers be expected to use it?

When a teacher resists jumping on the AI-in-education bandwagon, they are not being timid or out of touch. When they plan their lessons and grade papers without AI, they are not wasting time. When they don’t teach students how to use it, they are not being irresponsible. By focusing not on their students’ ability to use generative AI but on their students’ ability to be generative and thus thrive in a world that can sustain them, they are absolutely thinking about the future.