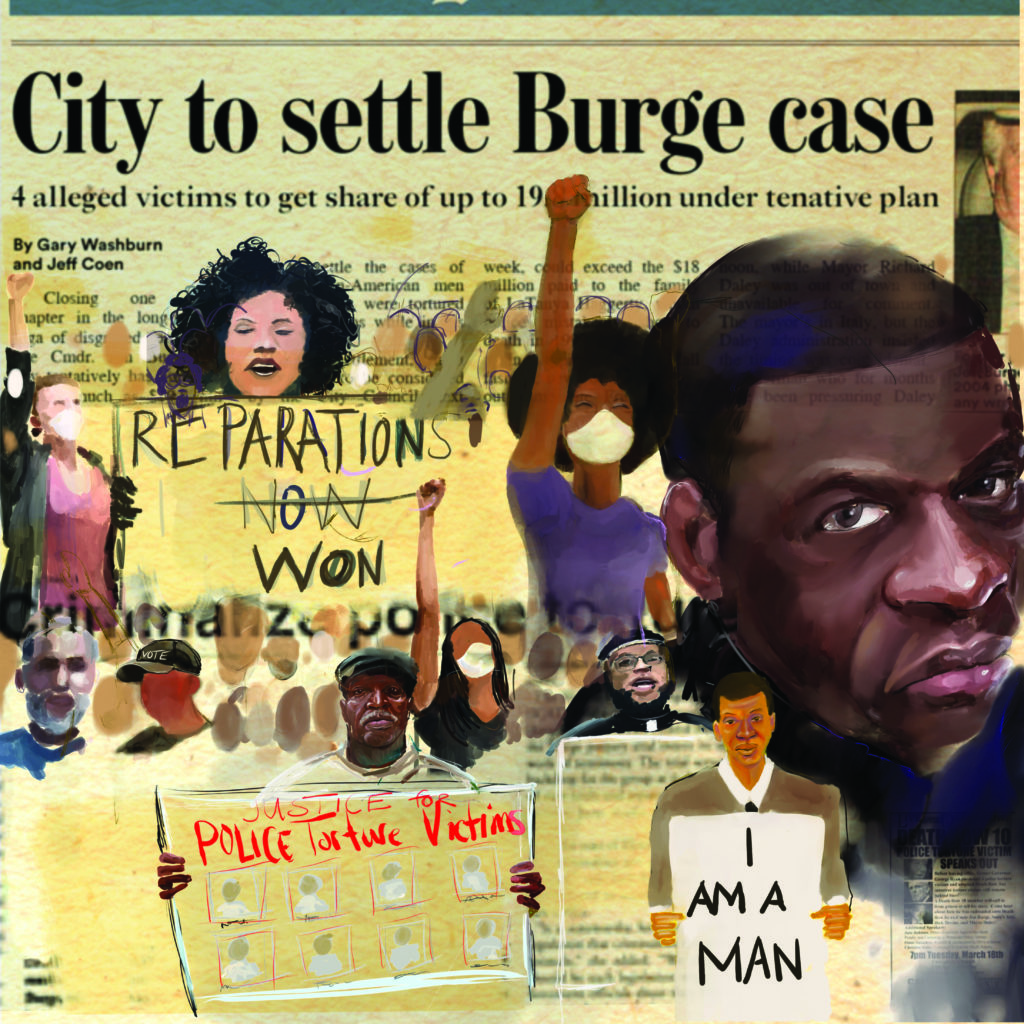

Reparations Can Be Won — and Must Be Taught

Lessons from the Chicago Public Schools' Reparations Won Curriculum

Illustrator: Howard Barry

I believe teachers and our union should fight alongside our communities for social, economic, and racial justice. But not all educators share that view. Some argue for neutrality. For some, the Reparations Won curriculum tells a particularly challenging history. However, educators can and must teach this story about how Black survivors of police torture in Chicago won an unprecedented and historic reparations package.

Plainly stated and sparing the awful details, Chicago Police Commander Jon Burge and officers beneath him tortured more than 100 Black men between 1972 and 1991. The physical and psychological abuse was varied, extensive, and horrifying and was used to elicit mostly false confessions that led to convictions and long prison sentences.

Although there were some victories and important efforts throughout the years, there was no reckoning or acknowledgement of the full breadth of the torture until 2015. The grassroots organization Chicago Torture Justice Memorials (CTJM) formed in 2011 and developed a pivotal campaign that included reparations. Years of protest and political pressure finally led to the passage on May 6, 2015, of an unprecedented city ordinance that included:

• An acknowledgement and condemnation of the torture.

• A formal apology to those affected by the torture.

• The formation of a commission to disseminate monetary reparations to the survivors.

• The formation of a fund of $5.5 million to provide up to $100,000 to each torture survivor with a credible claim.

• The creation of a counseling and training center on the South Side for survivors, family, and anyone impacted by police abuse.

• Free city college tuition for the survivors and their family members.

• Job placement assistance to formerly incarcerated survivors.

• That Chicago Public Schools teach a curriculum in 8th and 10th grades about the history of the torture and the fight for justice.

• Hearings for torture survivors still in prison.

• The creation of a public memorial honoring the survivors and their fight.

• A minimum of $20 million for the reparations, counseling center, curriculum, and memorial.

• Legally pursuing the ending of Jon Burge’s police pension.

Chicago is the only municipality that has offered reparations to victims of police abuse. The comprehensive reparations package is a model for “reimagining what justice looks like” according to CTJM co-founder and longtime activist Alice Kim, and what can be won when we dream audaciously and strategize out of the legal box.

Making Reparations Teachable

Winning a commitment to teach the reparations fight was just the beginning. Actual curriculum had to be created. A couple of colleagues and I participated periodically in meetings convened by the Chicago Public Schools social studies office to work with teachers and other experts to write, pilot, and implement what became the Reparations Won curriculum units for both middle and high school. The district staff worked diligently to manage the differing expectations for the curriculum, and it went through many revisions. It could not possibly be perfect, but there was effort to make it as accurate, powerful, and teachable as such a complex history could be. (To see the full curriculum, go to websites listed at the end of this article.)

During the pilot implementation phase, I accompanied CPS officials on visits to three schools. I saw middle school students at a predominantly Black elementary school on the South Side engaged in an energetic debate about how people should be treated when stopped by police. Middle school students at a largely Latinx elementary school read primary and secondary source documents about the torture itself. Lightbulbs and chatter broke out in the room when they realized that Burge served only three-and-a-half years in prison. High school students at an all-Black South Side school grappled with the time and range of people it took to win the ordinance.

In their final forms, the middle and high school curriculum units use primary and secondary sources to allow students to uncover the history of the Burge torture and the decades-long fight that led to the city ordinance, and the development of the curricula itself. Since both the 8th- and 10th-grade curricula are required to be taught, they are not identical. The curriculum presents students with a foundational understanding in middle school and then asks students to go into more historical depth in high school. Both units incorporate social-emotional components, such as restorative circles and journaling, to let students reflect and process their reactions to this tough history. Both units profile the causes of the torture, testimonials of torture, and the broad array of people who sought justice for years.

Each unit has unique and, I believe, radical features. The middle school unit focuses on the roles and responsibilities of police. Early on, lessons ask students to imagine that they are creating a new city and to decide if they want their new city to have a police force. If they do, they must write a rationale and describe what the mission of police should be. It is a huge victory that the unit boldly allows students to question the assumption of the need for police in the first place. Without forcing students to take a certain position, this exercise allows the abolition of police to be a rational vision for the future. In the closing activity, students stage a classroom town hall aimed at developing strategies to improve community-police relationships. The final assessment prompts students to write their own individual op-ed pieces based on what they’ve learned.

Building on the middle school unit, the high school one is framed around four main factors that allowed the torture to occur, and how major failures related to each of the factors enabled survivors to be victimized, incarcerated, and dismissed for years. At the unit’s conclusion, students evaluate whether the reparations package was sufficient to provide justice for the survivors. For the high school final assessment, students design their own proposal for an appropriate memorial connecting them directly to the outstanding work of fulfilling the ordinance’s promise of an actual city memorial.

Responding to Pushback

Pushback has emerged from predictable communities: predominantly white neighborhoods with a high concentration of police officer residents.

In January 2017, while the curriculum was being piloted, Chicago Teachers Union colleagues and I received about 40 responses to a survey of social studies teachers. How much did educators know and what did they feel about this curriculum? What excited and worried them about teaching the curriculum?

A sample of comments demonstrates their range of thinking:

• “I believe this is an inappropriate intrusion into the classroom. I would expect the CTU to stand up for the expertise and autonomy of social science teachers and refuse to support a court-ordered curriculum.”

• “Most importantly, won’t this further divide Chicago youth and Chicago police officers? Have you considered the conflict of interest regarding CPS teachers being asked to teach such a curriculum? Many of us are children, spouses, and parents of Chicago police officers.”

• “It will allow individuals who suffered injustice [to] have their voices and experiences heard and lessons passed on to future generations.”

• “We’ve been discussing the role of the police at great length since Ferguson. Even children of cops have strong opinions about what should and should not happen, including alternatives to policing.”

We expected this varied reaction. Winning a broad understanding of the value of teaching the Reparations Won units requires time and ongoing education. In April 2017, after the pilot phase, CPS had all schools send social studies teachers and counselors to a three-and-a-half-hour mandatory professional development (PD) session. I attended one session on the far north side in Uptown. Most of the educators were white. The teachers were quiet, especially when torture survivors Anthony Holmes and Darrell Cannon told their stories. The reactions of teachers at many of the South Side PD sessions, I was told, were different. Majority-Black educators emoted vocally about the imperative to do right by the curriculum.

While the district PD was well done, we at the CTU thought that we could and should provide teachers an optional, more in-depth experience. I worked with a racially mixed group of six CTU teachers to develop and facilitate our own PD. We created three modules: one that focused on what teachers should do before teaching the curriculum, one on the best practices for teaching it, and the final one on how to engage students in reflection and action after learning the curriculum.

Some educators are taking responsibility for addressing concerns on their own. I learned, after the fact, that a teacher at a predominantly white school in Jefferson Park, on the far northwest side of Chicago, ran a meeting in September 2017, with the support of her principal, where she took parents through the curriculum page by page to allay their fears.

Dustin Voss, one of the original pilot teachers and a CTU delegate, taught the curriculum again in the 2017–2018 school year and had Cannon come to speak to his class for the second year in a row. Of this visit, a student wrote: “You could tell that he wasn’t here just to tell his story. Darrell Cannon came to inspire us to make change where we see it needs to be made. . . . He was motivating us to want to fight to fix the problems that might affect us deeply by telling us how he changed his own life and the lives of many other people.”

FOR THE CURRICULUM, GO TO:

Middle school — blog.cps.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/ReparationsWon_MiddleSchool.pdf

High school — blog.cps.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/ReparationsWon_HighSchool.pdf

FOR THE CHICAGO CITY COUNCIL ORDINANCE ON THE CURRICULUM:

Support independent, progressive media and subscribe to Rethinking Schools at www.rethinkingschools.org/subscribe