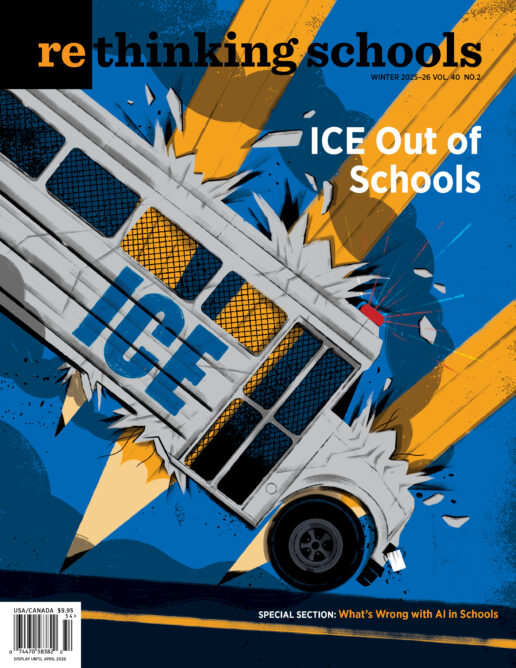

Recipes for Resistance

Students, Families, and Teachers Confront ICE Through Community

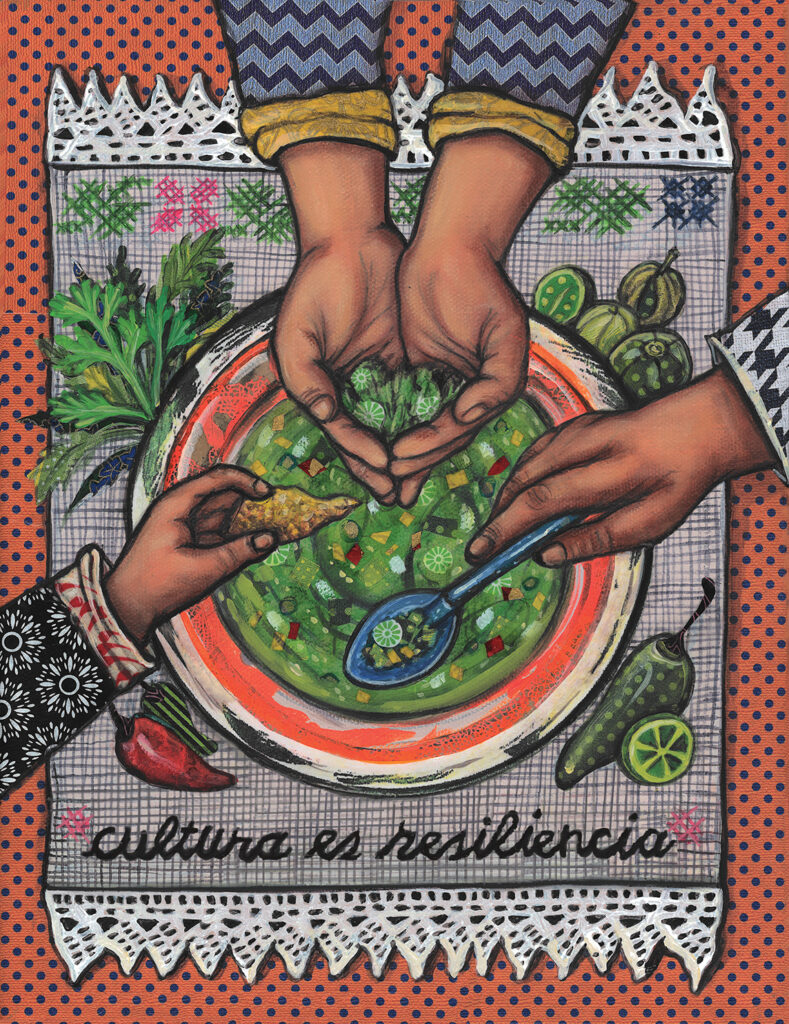

Illustrator: Angelica Contreras

One frozen morning in early 2025, I sat at the projector in my classroom. My class sat on the carpet with clipboards and pencils ready to practice the skills of today’s mini-lesson. “Turn to your shoulder partner and describe this scene with all five senses.” The orchestra of kid talk filled the room. One boy left his work in his square and sauntered up to me. “What’s up?” I asked. “Look, Mr. Irons.” He held a piece of scrap paper with torn edges and the artistic handwriting of an adult showing two names and two phone numbers.

“My mom, she gave me this. Is her number and my sister’s number. She tell me, si la migra me lleva, no tengo que decir nada [if ICE takes me, I shouldn’t say anything] and I have to call her and call my sister.”

Stunned, I drew in a breath. “How does that make you feel?”

“Sad. And scared.”

“You don’t deserve this. Your family doesn’t deserve this. All the teachers here love you, and we are fighting for you.”

He nodded, stuffed the paper back in his pocket, and sat down with his clipboard. I looked out the window. In the distance, I heard the partner talk switch from descriptive language to Pokémon, but I needed a moment to collect myself before continuing on. The Washington Monument is visible from my classroom window, and as I stared at it piercing the heavy sky hovering overhead, my student’s soft words echoed in my mind.

Since the second inauguration of Trump, these stories have become commonplace at the dual-language school where I teach in Washington, D.C. Kids come to school carrying emergency plans in their backpacks and worries in their hearts. Our school’s administration responded to the unfolding crisis with immediacy, organizing Know Your Rights sessions for families and coordinating with partner organizations in the community. Two other teachers and I wondered what more we could do to offer support, or at least respite, to our students and their families. We wanted to create a space where our school’s Spanish-speaking families could gather, be celebrated, and find joy. In those dreary, frozen winter days, we strategized together.

The three of us had spearheaded a partnership with the Washington Youth Garden to provide outdoor learning to our kids throughout the year. This organization, based on a lush one-acre education garden in the National Arboretum, works with D.C. educators to build gardening programs at their schools. Students learned to grow food, care for plants, and observe the cycles of water and of life. Whatever event we decided on for our school’s families, we were certain that including the Washington Youth Garden would amplify its impact. We sat with our partners one afternoon to discuss possibilities for materializing our ideas. The event should center families currently targeted by ICE, and it should provide an opportunity for families to share knowledge and resources with each other. The event should also celebrate the cultures and identities represented in our school community, and it should offer emotional nourishment in these dark days. Ultimately, we decided on hosting a cooking night exclusively in Spanish.

A cooking night seemed so natural to the environment we aimed at creating. But we needed to decide on a recipe. Ideally, the recipe should reflect the community and, better still, should come from a community member. My fellow 2nd-grade teacher offered two of her family’s salsa recipes: salsa de jitomate and salsa verde. A family recipe is sacred. It transmits memory, love, pain, resilience. A family recipe teaches how to create art and sustenance in all circumstances. Her recipe would offer the warmth we sought for the event. We printed and laminated recipe cards to hand out that evening, and the Washington Youth Garden would purchase the groceries we needed, as well as hot plates, kid-safe knives, and cutting boards. We would bring the other items we needed, like blenders, pans, and bowls. With that settled, we booked an afternoon at the school’s Family Center, where we typically hold IEP meetings, charlas with the principal, and — most recently — informational Know Your Rights sessions.

In the month leading up to the cooking night, we organized our communication strategy. We used every possible method to reach out to families and encourage them to come. We first created a flier in Spanish advertising the event and distributed it to teachers in each grade level to pass out to their classes. Interested families could return the flier with their contact information, and they could scan a QR code on the flier that directed participants to fill out a Google Form to confirm their attendance. Coordinating with our school administration, we sent out a school-wide invitation on Remind with the Google Form linked to the message. Two weeks prior to the event, we messaged families that had already confirmed to remind them of the time and place. The week of the event, we passed out fliers each afternoon at dismissal, speaking with as many families as we could. Those we didn’t see at dismissal, we called. We asked every day up to the afternoon of the event. Initially, 15 families had confirmed. As we walked in the Family Center that afternoon, 25 families showed up.

We directed everyone in the room to one of two group tables. Our partners at the Washington Youth Garden said a few introductory words, which we translated into Spanish, and then we followed with our own introduction to the event. I explained what each group would be making: My teammate’s group would make salsa de jitomate and my group would make salsa verde. “Al final, vamos a tomar tiempo para probar las salsas y platicar. [Afterward, we will take some time to try the salsas and chat.]”

All the ingredients were ready in bowls at the center of the table. Tomatillos, chiles serranos, jalapeños, garlic, and onions lay in wait as I distributed the kid knives and cutting boards to each of the children gathered around the table. I took out each vegetable and asked if the kids could identify them.

“That’s cebolla! Te hace llorar! [That’s onion! That makes you cry!]” I asked for volunteers to cut the onion in quarters, and two boys from 2nd grade were eager for the challenge. Their mothers sat behind them and coached them on how to hold the knife and the onion safely. They sawed vigorously into the onions, panting and taking breaks, until they had cut them into quarters. They beamed with pride at their strength and asked for another job.

“Ajo! A mí no me gusta. [Garlic! I don’t like that.]” One kindergarten girl made a face of disgust at the head of garlic I held in my hand. I gave her a little laugh. “Sí, es ajo. ¿Alguien sabe un truco para pelar un diente de ajo más fácil? [Yes, that’s garlic. Does anyone know a trick to peel a garlic clove more easily?]” Again, the children looked around for answers. One mother offered, “Tienes que aplastarlo primero, y luego lo puedes pelar fácilmente. [First, you need to smash it, then you can peel it easily.]” I asked this mother to demonstrate her instructions for the kids to try. After, I distributed one clove of garlic to every two kids (more than we needed), and everyone had a turn smashing and peeling the garlic. The kids giggled mischievously and punctuated their smashing with loud yells.

“O, son chiles picosos. [Oh, those are spicy chiles.]” Those we left whole.

“¿Y esto? ¿Quién sabe cómo se llama esa verdura? [And this? Who knows what this vegetable is called?]” The children grinned and looked around at each other in silence, until finally a different mother chimed in: “Eso es un tomatillo. [That’s a tomatillo.]” The kids were excited to share what they knew about each vegetable: how it grows, what it tastes like, where they have seen them before. They shared what foods they eat at home, what foods they ate in their families’ home countries, what they like to eat most of all. Children I had in class who were reticent to speak or often redirected during lessons had a moment to shine and feel valued.

With the vegetables prepared, we moved to a different table with a hot plate and pan. I asked one of the older kids to read the instructions on the recipe card: “Asar las verduras en un sartén hasta que se cambien de color. [Roast the vegetables in a pan until they change color.]” The children stood on one side of the heated pan with me, and their parents sat in chairs facing us. Meanwhile, their little siblings played with toys provided by our Family Center.

This was my first time ever making salsa verde, and I didn’t really know what I was doing. I followed the recipe and hoped for the best. Sadly, my best was lackluster. I threw all the vegetables in the pan at once with some oil and waited for them to char. We stood around the pan listening to the sizzle and pop, but no char appeared. Instead, the vegetables started releasing water and a soupy mess emerged. I looked out to the moms seated in front of me with panic on my face to see their teasing smiles in return. “Saca unas y dejar las dorar un poco más. [Take out some of them and let them crisp up a little more.]” I called in the kid reinforcements to salvage our roasting vegetables as best we could. The kids were energized by the crisis and sprang into action. They ran to grab me the bowl and shouted at me to hurry in taking them out of the pan. They were ecstatic that I had messed the recipe up.

On the other side of the room, the other group was blending their perfectly blackened vegetables, ready to go back in the pan for a second fry. The enticing scent of roasted chiles floated around the room as my teammate poured the blended mix into the hot pan. The delicate fragrance of a moment prior gave way to plumes of prickly smoke spiced with chiles rising from the spattering pan, and the room erupted in a frenzy. Parents coughed and rushed to open a window, while kids dropped to the floor coughing, laughing, and screaming in delight. My group finally abandoned hope for roasting the vegetables and threw everything in the blender.

Resistance can be homemade; its manifesto — a sacred recipe.

We poured the salsas in bowls and distributed them throughout the room with tortillas and chips. The kids were exuberant at having made something delicious. They ran from one bowl to the next, some fanning their tongues from the spice, others proudly showing their tolerance for chiles. As the children enjoyed their creation, my colleagues and I circulated throughout the room to chat with parents. We had previously agreed upon a communication strategy that would open the door for conversations about the increased raids but would not directly elicit information on the subject. The event sought to center and edify the school community; we would follow community members’ lead in conversations. We made certain to thank each person who had braved the frozen evening to participate and to reiterate the purpose of the event: “Queríamos crear un espacio para la alegría, para celebrar nuestra comunidad en este tiempo complicado [We wanted to create a space for joy, to celebrate our community in this challenging time].” Without hesitation, parents shared their experiences and their fears of the past few months.

Close encounters with ICE were ubiquitous. One mother described how she was walking up to a gas station and, seeing a large police presence, turned around. One officer yelled to her, sneering, “Hey! ICE isn’t here. You can come on in.” She was so shaken by the encounter that now she avoids that gas station. Another recounted ICE officers milling about outside of their apartment building, preventing her from leaving the house to walk her children to school. Someone else seconded that experience, saying their children were up until late, terrified that ICE would come through the door. The next day at school, their children’s teachers said they were falling asleep in class. Others gave tips on where in the city they have seen ICE setting up vehicle checkpoints and stopping pedestrians on the street.

As each recounted their own stories, they also shared ways to resist. One mother connected others with family and friends who could walk the group’s children to and from school when ICE was seen in the area. Everyone exchanged numbers to keep in contact and keep themselves safe. We also ensured that everyone present was added to a Signal group chat where other parents, teachers, and administrators shared information on ICE movements and resources for community safety. Along with recipe cards for families to take home, we provided Know Your Rights pamphlets from our school’s front office. As families left that afternoon, they expressed immense gratitude at the happiness they found in making salsa with their children and eager for more events like it.

This first cooking night showed us the power in creating space for joy. Now well into the 2025–26 school year, kidnappings and unlawful detainments have increased dramatically. Concentration camps like “Alligator Alcatraz” sprang up over the summer, and harrowing reports of abuse and deprivation in these places have managed to escape to the public outside. Children have returned to school telling stories of family members arrested, deported, or disappeared. A corps of volunteers must now escort many children to school whose parents cannot risk a daily walk through the streets. My phone buzzes all day with notifications from the Signal group chat alerting of ICE and other federal agents conducting arrests within blocks of our school. The need for joyful and strategic spaces like this first afternoon making salsa is all the more urgent.

The cruelty our students face is enormous and escalating. As we organize for their safety, we can also organize for their spirits. Resistance can be homemade; its manifesto — a sacred recipe. It can nourish and enliven. Resistance can be wielded in the hand of a mother as she helps her son cut onions, or in the fingers of a child trying their first creation in the kitchen. Resistance, like salsa, can be simple and spicy.