Reading Louise Erdrich to My Son

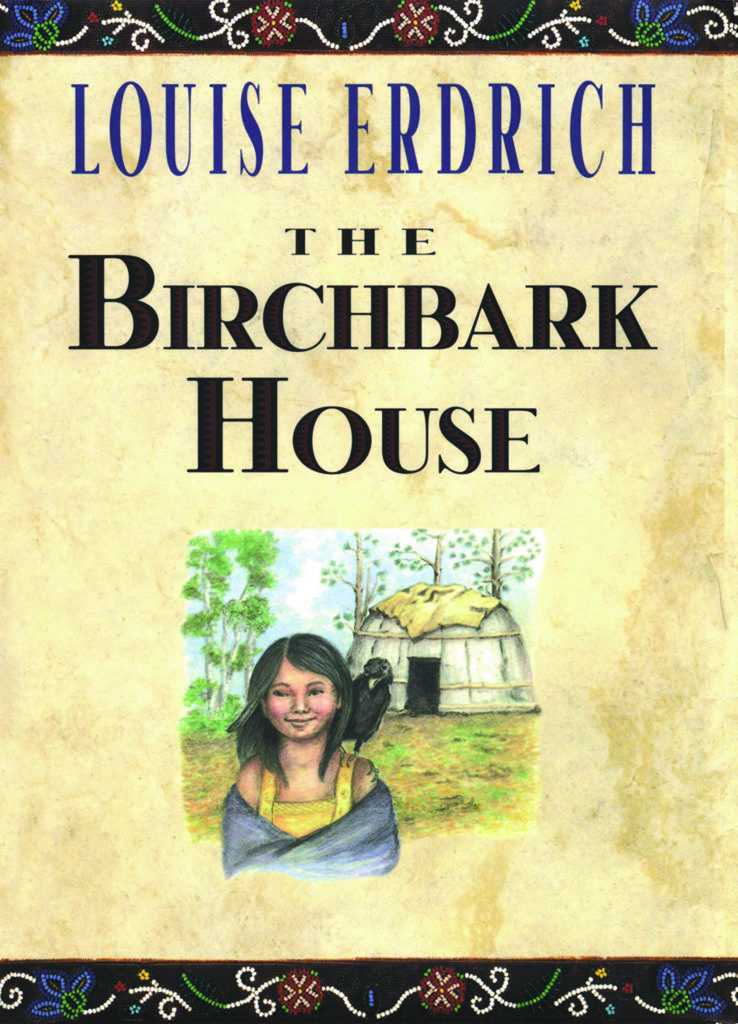

When my son Seeger was 8 years old, I brought home Louise Erdrich’s The Birchbark House from the library to read to him. I first spotted this book on the shelves in the children’s section a few years before, and I was thrilled to see Erdrich’s name on the spine of a “chapter book” for middle-grade readers. I was familiar with some of her adult novels from my college years and remembered appreciating Erdrich’s writing and perspective, so I wondered what stories she offered to children. My selection of her book that day was also part of a concerted effort to diversify the novels I was choosing to read to Seeger each night. We had been reading mostly older books by white, male authors like A. A. Milne, Roald Dahl, George Selden, E. B. White, and Lewis Carroll, because those were books I loved as a child. I had also read Laura Ingalls Wilder’s stories to Seeger, and really wanted to prompt conversation about and counteract the racist perspective we had encountered in that famous — and infamous — narrative of westward expansion.

The Birchbark House is the first book in a series that Erdrich, a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa (a band of the Anishinaabe also known as Ojibwe), wrote about her own family’s experience of being forced from their ancestral home. It was published in 1999 and was a National Book Award finalist for young people’s fiction that year. Over the past 15 years Erdrich has published four more books for the series, including two Scott O’Dell Award for Historical Fiction winners: The Game of Silence and Chickadee.

I asked around before I started reading to see if any friends had read this series with their children. Even though I know many people who are familiar with Erdrich’s poetry and novels for adults — especially her National Book Award winner, The Round House — I could find only a few teacher-librarian colleagues who knew about the Birchbark series for children. One friend, another teacher and parent, had read the first book years ago. When I asked if she thought it would be a good read-aloud for my 3rd grader, she cringed, and said, “Isn’t that the book that deals with smallpox?” It was clear she thought this topic too serious for a child my son’s age. But I decided to read it to Seeger anyway, and we were both quickly captivated by the story.

The Birchbark books chronicle the life and seasonal experiences of an Ojibwe family, starting from the perspective of a 7-year-old girl named Omakayas. Her family lives on an island in Lake Superior, and later on the Great Plains during the mid- to late 1800s. Erdrich meticulously researched her own family’s and tribe’s experiences during those years and based the Birchbark series around that history: “I wanted to tell the story of where my mother’s people had come from,” Erdrich said in an interview for Teaching Books. Readers who are not familiar with Ojibwe culture and history will learn a tremendous amount from the author’s beautifully written and detailed depictions of daily life, as well as her intricate pencil drawings and maps. Many words in the Ojibwe language are used in the text, and Seeger and I enjoyed referring to the glossary and pronunciation guide at the back of each book.

There are enough adventures and gripping survival scenarios in the Birchbark series to keep young readers engaged, but themes of community, conflict, and resilience are gracefully interwoven and drive the narrative. Strong female characters have a big presence in these books, as they do in many of Erdrich’s other writings. One of our favorite characters is Old Tallow, a tough, eccentric elder who lives and hunts alone with her beloved dogs. We learn she has ousted various husbands, but she has a tender and protective relationship with young Omakayas. Old Tallow, along with Omakayas’ strong-willed cousin Two Strike, both defy traditional roles of women and provide refreshing alternatives within their community.

Erdrich delivers a compelling, personalized account of what happened to American Indian tribes when government officials, missionaries, traders, and settler families like the Ingalls, from the still-popular Little House series by Laura Ingalls Wilder, arrived on the scene. “My ancestors were driven by the westward expansion of European settlers who wanted more and more and more land,” Erdrich said. “The Ojibwe were driven out onto the plains. Eventually, my great-grandparents ended up all the way over in Montana.” The Birchbark series relates this painful time of forced migration, along with other injustices and hardships suffered by so many tribes: promises and treaties broken by the government, missionaries’ attempts to convert Native people, neighboring tribes fighting for diminishing resources, the decline of buffalo populations, and yes, smallpox.

Seeger and I cried together when Omakayas’ baby brother died of smallpox in The Birchbark House. We had several conversations about that disease, about how and why it was transmitted accidentally and intentionally by Europeans to Indigenous people all across the Americas. When I choked up another night as the U.S. government forces Omakayas and her family from their island home — and they must leave their dog behind because he can’t fit in the canoe — Seeger gently took the book from me and continued reading out loud until I could gather myself enough to continue. “These are really good books, Mom,” Seeger told me more than once. He is clearly not too young to hear this historical truth, even while it is difficult for me to tell it. Erdrich’s stories relate painful experiences but they are also full of joy and humor. I think this complexity is what makes them so compelling.

I realized what an impression the Birchbark series was having on my son when he visited his school library for the first time at the beginning of the school year and selected a nonfiction book about the Ojibwe tribe. He brought it home for us to read together, and we talked about the connections he made to the novels. “This is like Omakayas’ summer house,” he said, pointing to a black-and-white photograph of an Ojibwe family outside their birchbark lodge. “See, this is how they dried their fish on that wooden frame” and “I think this is how Pinch [Omakayas’ little brother] made his fish traps.” We were delighted to see Louise Erdrich featured in this not-too-outdated library book, right alongside Winona LaDuke.

There are parts of the stories that deal with sad and difficult truths — starvation, death, betrayal, abuse, kidnapping, alcoholism — and for my son, reading the books together has been an introduction to some of these hard facts of life. These tough topics are balanced beautifully by the strength of Omakayas and her family, their traditions, loyalty, hope, and the possibilities born from change in their lives. Silly antics and a few buffoon characters made us laugh out loud, frequently. Erdrich offers parents and teachers an excellent, age-appropriate platform for talking with children about history, and about having agency in our lives. And certainly, reading stories that truthfully address the injustice and racism that has always been part of our country’s past feels especially necessary right now.

Wilder’s Little House series (published between 1932 and 1943) tackles some of the same tough topics and encompasses almost the same time frame as the Birchbark series, but from the perspective of the author’s white pioneer family. There is very little in Wilder’s stories, if anything, to challenge the expansionist, racist, and sexist viewpoint from which they are told. Despite this, the Little House books continue to have a loyal following of adults and children worldwide. Many people, like me, remember the stories fondly from childhood — but may have a completely different experience reading them as adults. I am increasingly disturbed by the fandom that seems unaware and unaffected by Wilder’s entitled frame of reference. Laura Bush, for example, wrote the foreword to the newest 2017 edition of the Little House books, in which she lovingly says the books have “captured and preserved our nation’s past for each new generation of readers.” This kind of response to Wilder’s books glorifies a whitewashed, colonial past and does nothing to contribute to a more critical and accurate understanding of history.

The Little House books have never gone out of print since their first publication, almost 100 years ago. This is likely due in large part to the popular television adaptation in the 1970s and ’80s. After that, many spin-off books were written, and now a cursory internet search reveals websites devoted to Laura Ingalls Wilder-inspired crafts, recipes, sewing patterns, and road trips. A few years ago a new Little House on the Prairie musical toured the West, while visitors flock annually to several Laura Ingalls Wilder museums, historic sites, and events, not to mention drive on the Laura Ingalls Wilder Historic Highway. At a birthday party in San Francisco for my son’s friend, I was surprised that one of the most well-received gifts was a set of the first three Little House books. (Seeger told his friend she should read the Birchbark series, too: “It’s kind of the same, and kind of like the opposite,” I overheard him saying to her.)

I wish my son’s teachers would read the Birchbark series in his classroom and facilitate thoughtful conversations about the hard parts. And I hope that engaged parents, teachers, and librarians will help young readers understand and challenge the Eurocentric and antiquated perspective of Wilder. Comparing and contrasting the two series can be an experience in critical reading, but it may take some guidance for young readers. When asked by interviewers from the Horn Book about the parallels between her books and Wilder’s, Louise Erdrich said she didn’t start off writing with that intention, but:

The migration across Minnesota into the Dakotas, and the warmth of family life, is something that these books have in common with the Little House series. I am happy that they are being read together, as the Native experience of early Western settlement is so often missing in middle-grade history classes.

Seeger and I were happy to learn that Erdrich plans to continue writing her Birchbark stories until there are eight titles, covering the span of 100 years in the family of Omakayas. In a glowing review of the Birchbark series, Debbie Reese, a scholar and astute critic of children’s books with American Indian themes and characters, wrote on the American Indians in Children’s Literature website:

The world might be a better place if we replaced every copy of Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie with Erdrich’s series. In Erdrich, children see human and humane, fully developed Native characters whose culture is in conflict with those who want what they have.

In June 2018, the American Library Association (ALA) decided to rename their prestigious Laura Ingalls Wilder Award, changing it to the Children’s Literature Legacy Award. Since 1954, the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award honored authors and illustrators whose books have made a substantial and lasting contribution to children’s literature. In announcing the change, a joint statement from the presidents of the ALA and the Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC) said, “Although Wilder’s work holds a significant place in the history of children’s literature and continues to be read today, ALSC has had to grapple with the inconsistency between Wilder’s legacy and its core values of inclusiveness, integrity, and respect, and responsiveness through an award that bears Wilder’s name.”

I applaud this decision and think it reflects the growing awareness and intolerance of institutionalized racism we see in many public spheres. Such steps, along with the continued publication of more diverse perspectives in books for both children and adults, will encourage all of us to think more critically. The stories we choose to tell children have great power to frame their understanding not only of history, but also of our present times.