Queering Black History and Getting Free

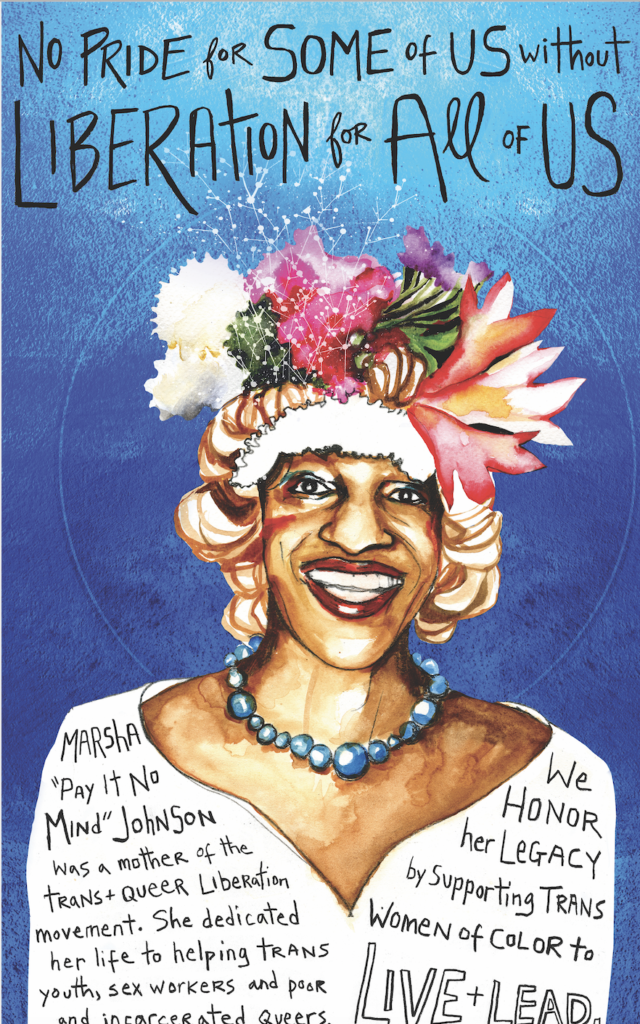

Illustrator: Micah Bazant

I am a queer Black woman. By this I mean that my sexuality exists outside the margins, between the approved boundaries, beyond the limits of most imaginations. A queer thing is a thing that existing words cannot yet adequately describe, a thing that our language and our boxes have not yet evolved to capture. So, what does queering something mean? To me it means turning the thing on its head: questioning its assumed narratives, reworking its categories, and upending its status quo.

Let’s queer Black history.

Lifting Up the Stories of Black LGBTQ People

Queering Black history means lifting up the stories of Black LGBTQ people. It means resolving that not one more student learns about the “I Have a Dream” speech without learning about Bayard Rustin, the man who led the planning of the March on Washington — at least not on our watch. It means really learning about him: knowing his contributions to the Civil Rights Movement, reading Time on Two Crosses right next to The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr., having discussions in our classrooms and on our social media about “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” while also discussing why Bayard Rustin too was arrested, how he was relegated to the background by his peers, and what we must do to prevent that from ever again happening in the Black freedom movement.

Queering Black history means canonizing Marsha P. Johnson as a matriarch of Black America. Putting her face on those calendars and poster collages right next to Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Coretta Scott King, and Michelle Obama. It means studying her ACT UP campaigns in high school classrooms. It means mourning her too-early death just as we mourn the deaths of cisgender men like Malcolm and Medgar. It means examining why it took 20 years for the NYPD to investigate that death as a murder, and having conversations about the role of the Black freedom movement in bringing about trans liberation today.

This article originally appeared on Black Youth Project and also appeared in the book Teaching for Black Lives.

Complicating the Stories of the Historical Figures We Know

Queering Black history goes wider and deeper than the inclusion and re-centering of queer folks. Remember that “queering” also means reworking. We must rework and complicate the stories we tell about the Black figures we are familiar with.

Rosa Parks, for example, was not only told to get to the back of the bus. She was also told by Montgomery NAACP president E. D. Nixon, with whom she served as chapter secretary, that women should stay in the kitchen. As we study her resistance against both attacks on her Black womanhood (and her organizing against sexual violence), a queering of Black history requires us to ask why we leave out that piece of the story, and how we can ensure that our contemporary movements are safe spaces for people living at the intersections.

Billie Holiday was a prolific jazz singer. She was also addicted to heroin, and the first major target of the federal government’s war on drugs. Harry Anslinger, virulent racist and first head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, intentionally turned a blind eye to the addictions of prominent white entertainers while obsessing over Holiday and his dream of bringing the full force of the federal government down upon her head. She died shackled to a hospital bed, denied appropriate treatment by the federal government, with police officers at her door. Billie Holiday has an important place not only in the history of Black music, but also in the history of Black people, the police state, and resistance.

Seeking Out New Stories

But if we are to queer Black history then we must dig deeper, do more than adding nuance to the narratives of those we already know and love. We also have to study and celebrate the Black people who have been erased, hidden from our collective memories. We have to move beyond the shiny Negroes — the astronauts, entrepreneurs, athletes, entertainers, and organizers who have been deemed respectable enough to be worthy of our memory. We have to look between the cracks and find our incarcerated heroes, our undocumented leaders, our luminary sex workers, the people who systems of oppression most desperately want us to forget. And we have to teach those stories to each other.

We have to do the work of intentionally remembering people like Carol Crooks. I learned her name while doing research for this essay. She doesn’t have a Wikipedia page. But she is worth remembering. Crooks was a woman who became an organizer while incarcerated at Bedford Hills, a maximum security prison in New York.

In February of 1974, Crooks had a severe migraine and asked to be taken to see the prison nurse. When her guard denied her request, she tried to push past her and get to the nurse anyway. In response to this incident, Crooks was beaten, stripped naked, and placed into a solitary confinement cell for three days. Crooks later filed a lawsuit challenging the practice of sentencing inmates to solitary confinement with no trial or formal charges. She won her case, and the warden was found guilty of unconstitutional treatment of a prisoner.

That August, Crooks was returned to solitary with no formal charges. The next morning, a group of women went to the warden and demanded Crooks’ release, alleging that the solitary confinement of Crooks was retaliatory. The women were ignored and told to go to bed three hours earlier than usual. They refused to comply. The guards began to assault the women in response to the insubordination. The women seized the guards’ weapons and fought back. They took over the prison in what is now known as the August Rebellion, until state troopers subdued them about four hours later.

Carol Crooks is part of a queered Black history.

Disrupting the Centralized, Charismatic Leader Narrative

Next we must question the very ideal of Black history through the lens of the individual. We must ask ourselves: Why does the history we choose to remember so often come in the form of charismatic and solitary pioneers, centralized leadership, and the folks out front?

Queering Black history means remembering everyday people, the struggles they faced, and the work they did. It means recognizing ordinary Black people who were told their lives didn’t matter, but who still contained a fierce will to live, and love, and fight for freedom. It means valuing all different types of Black leadership — the folks who were behind the scenes, who were quiet, who were less than charming, who didn’t win but set the stage for those who later would, who rose to the occasion because they had to and then went back to their regularly scheduled lives. It means celebrating collectives, and group efforts, and conglomerations of movers, shakers, and neighbors whose names we won’t ever know.

I want us to upend the status quo by including the Contract Buyers League in our Civil Rights Movement narrative. The Contract Buyers League was a group of more than 500 people living on the South Side of Chicago in the 1960s who had bought their homes through predatory loans after being shut out of the mainstream home loan market by racist laws. They banded together, filed suit against the speculators who were cheating them, and demanded their money back. They lost. But the Contract Buyers League is part of a queered Black history.

I want us to queer Black history by teaching about the residents of the Arthur Capper public housing community in Washington, D.C. These residents saw businesses, and particularly grocery stores, disinvest from their Southeast community in the 1970s. They decided to take matters into their own hands. As the mythology of entitled Black welfare queens and lazy project thugs was gaining steam across the country, the residents worked together to start a community-owned small business. They built the Martin Luther King Jr. Co-Op Food Store and harnessed the power of cooperative economics to nourish a Black community trying to survive in a hostile white world. We don’t know the names of everyone who accomplished this feat, but the residents of the now-demolished Arthur Capper public housing project are part of a queered Black history.

Acknowledging Our Dirt, Holding Our Pain

A queered Black history cannot be sanitized. Filing down Black history’s sharp edges would make sense if the only point of studying it was to make ourselves feel good. Sweeping the flaws of our Black icons under the rug would be reasonable if the goal of Black history was to convince a white society that Black people are good and smart, that we can be honorable too, that our lives matter. But I don’t believe that either of these goals are what Black history is about.

I believe that we learn Black history because doing so will help us to get free. And in order to accomplish this goal, to be able to learn from the fullness of our past, we have to approach it with a queer lens. We have to bring to Black history a quality that the Black queer community embodies at its best — the unconditional acceptance of people’s full and real selves.

Our history is what it is. Sometimes we didn’t overcome. Sometimes our faves were misogynists. Sometimes our idols were reckless and led movements into the ground. Sometimes effective and powerful Black leaders were on crack. Sometimes our stories are not glistening tales of hope and triumph and movin’ on up, but stories of mistakes made. Sometimes they are stories of pain and loss, death, and things being taken from us. But they are stories that have something to teach us nonetheless.

Let’s queer Black history. Let’s re-imagine it as an opportunity to celebrate Black heroes, leaders, and everyday people. Let’s use it to remember and mourn the Black lives that white supremacy has ripped from our arms. Let’s use it as a chance to learn from the lives of Black people at all different intersections, Black people whose sweat and tears, laughter and joy, victories and mistakes have brought us to where we are today. Let’s make learning Black history about getting free.