Putting Out the Linguistic Welcome Mat

Honoring students: home languages builds an inclusive classroom.

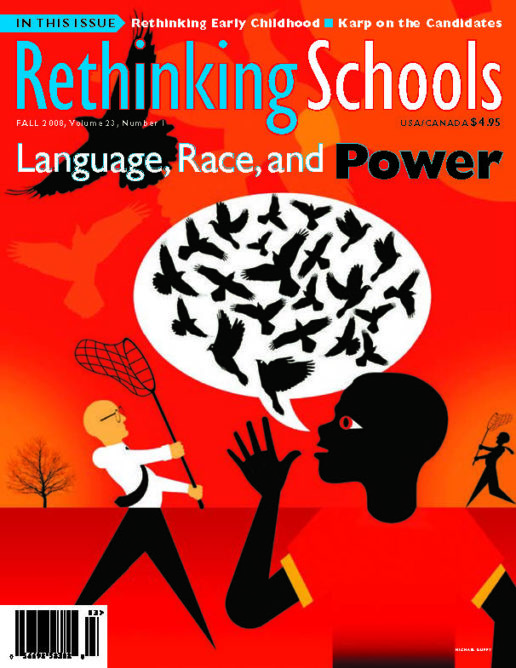

Illustrator: Michael Duffy

“That’s not Standard English!”

“You’re black, you ought to understand them.”

“They’re thugs — I know it.”

“Let’s teach them regular U.S. history first; the other stuff will come later.”

In this standardize-test-and-punish nation, there’s too little consideration for how race matters in school — from the language we prize or penalize to textbook content to how teachers discipline students. The following essays argue for critique and inclusion — with race at the center. — the editors

My friend Karen works as a relatively new principal in a rural Oregon school where the sons and daughters of winery owners rub elbows with the sons and daughters of their field workers. Recently, she recounted a story about a typical day: “When I came into my office after lunch duty, three Latino students sat waiting for me. The students told me the substitute kicked them out for speaking Spanish in class. After verifying the story, I told the substitute her services would no longer be needed at our school.”

Karen is a full-time warrior for students. She battles remarkable linguistic prejudice and historical inequities to make her school a safe community for her Latino students. Before she arrived on campus, for example, school policy excluded Spanish-speaking English language learners from taking Spanish classes. Latino students had to enroll in German classes to meet their world language requirement.

At another urban school, in the Portland area, a group of teachers tallied the grammatical errors their administrator made during a faculty meeting. Their air of superiority and smugness made my teeth ache. This same smugness silences many students in our classrooms when we value how they speak more than what they say.

“Nonstandard” language speakers must negotiate this kind of language minefield whenever they enter the halls of power — schools, banks, government agencies, and employment offices. Language inequity still exists, whether it’s getting kicked out of class for speaking in your home language or being found unfit for a job, a college, or a scholarship because of your lack of dexterity with Standard English.

As educators, we have the power to determine whether students feel included or excluded in our schools and classrooms. By bringing students’ languages from their homes into the classroom, we validate their culture and their history as topics worthy of study.

A Curriculum on Language and Power

Author Toni Morrison (1981) writes about the power of language, and Black English in particular:

It’s the thing black people love so much — the saying of words, holding them on the tongue, experimenting with them, playing with them. It’s a love, a passion. Its function is like a preacher’s: to make you stand up out of your seat, make you lose yourself and hear yourself. The worst of all possible things that could happen would be to lose that language. There are certain things I cannot say without recourse to my language.

These days, most of our schools and school boards fashion mission statements about “embracing diversity.” Multilingual banners welcome students and visitors in Spanish, Russian, and Vietnamese in the hallways of school buildings. But in the classroom, the job of the teacher often appears to be whitewashing students of color or students who are linguistically diverse, especially when punctuation and grammar are double-weighted on the state writing test. If we hope to create positive communities in which students from diverse backgrounds can thrive academically, we need to examine how our approach to students’ linguistic diversity either includes or pushes out our most vulnerable learners.

During 30 years as a language arts classroom teacher, I realized that if I wanted my students to open up in their writing, to take risks and engage in intellectually demanding work, I needed to challenge assumptions about the superiority of Standard English and the inferiority of the home language of many of my black students: African American Vernacular English, Black English, or Ebonics. When students feel attacked by the red pen or the tongue for the way they write or speak, they either make themselves small — turning in short papers — or don’t turn in papers at all. To build an engaging classroom where students from different backgrounds felt safe enough to dare to be big and bold in their writing, I had to build a curricular platform for them to stand on.

I started this work by intentionally inviting students to tell their stories in their home languages. I brought in August Wilson’s plays, Lois Yamanaka’s stories, and Jimmy Santiago Baca’s poetry to validate the use of dialect and home language. But I learned that this wasn’t enough. To challenge the old world order, I needed to explore why Standard English is the standard — how it came to power and how that power makes some people feel welcome and others feel like outsiders.

I finally realized that I needed to create a curriculum on language and power that examined the roots of language supremacy and analyzed how schools perpetuate the myths of the inferiority of some languages. I also discovered that students needed stories of hope: stories of people’s resistance to the loss of their mother tongues and stories about the growing movement to save indigenous languages from extinction.

Legitimizing the Study of Ebonics/Black English

Depending on how many pieces of the unit I include, this curriculum takes 5-10 weeks. Students watch films and read literature, nonfiction texts, and poetry. They write narratives, poetry, and a culminating essay about language. For their final exam, they create a take-it-to-the-people project that teaches an audience of their choice one aspect of our language study that they think people need to know in order to understand contemporary language issues. The curriculum includes any of the following five segments: Naming as a Practice of Power; Language and Colonization; Dialect and Power; Ebonics; and Language Restoration.

During this unit, we do discuss code-switching, or moving between home language and the language of power — Standard English — during our readings. As a teacher in a predominantly African American school where the majority of students exhibited some features of African American Vernacular English (AAVE, also called Ebonics or “Spoken Soul”), I needed to learn the rules and history of the language so I could help students move between the two language systems. In my experience, teaching black students the grammar structure and history of AAVE evoked pride in their language, but also curiosity. All students — not just African Americans — benefited from learning that African American language has a highly structured grammar system.

Teaching about Ebonics has been a no-go zone for many teachers since the controversy over a 1996 Oakland School District resolution that recognized Black English as a language of instruction. Stanford linguistics professor John Rickford noted in his book, Spoken Soul:

Ebonics was vilified as ‘disgusting black street slang,’ ‘incorrect and substandard,’ ‘nothing more than ignorance,’ ‘lazy English,’ ‘bastardized English,’ the language of illiteracy,’ and this ‘utmost ridiculous made-up language.’ (Rickford, 2000, p.6)

As Rickford pointed out, the reactions of linguists were much more positive than those of most of the media and the general public. Although they disagree about its origins, “linguists from virtually all points of view agree on the systematicity of Ebonics, and on the potential value of taking it into account in teaching Ebonics speakers to read and write.” (Rickford, 1997)

In an African American Literature class I recently taught at Grant High School in Portland, Ore., I introduced the Ebonics part of the language curriculum by giving the 31 students (28 of whom were black) a concept chart and asking them to fill in a definition of Ebonics, write a few examples, and note where it originated. All but one student wrote that Ebonics is slang. Most wrote that Ebonics came out of Oakland or the West Coast or the “ghetto.” It was clear that their impressions were negative.

None of the black students in the group used Ebonics/AAVE exclusively. But many of them used aspects of Ebonics in both their speech and their writing. One of my goals was for students to recognize the difference between slang and Ebonics/Black English when they hear it in their school, churches, and homes — and to be able to distinguish it when they are using it. The term “Ebonics” (from ebony and phonics) was coined by Professor Robert Williams in 1973, during a conference on the language development of black children (Rickford [2000] p. 170) In her essay, “Black English/Ebonics: What It Be Like?” renowned scholar and linguist Geneva Smitherman writes that Ebonics “is rooted in the black American Oral Tradition and represents a synthesis of African (primarily West African) and European (primarily English) linguistic-cultural traditions.” (Smitherman, 1998)

In the class, we read Rickford’s essay, “Suite for Ebony and Phonics” aloud together paragraph by paragraph, stopping to discuss each part. Rickford points out that Ebonics, or African American Vernacular English, is not just “slang”; it includes “distinctive patterns of pronunciation and grammar, the elements of language on which linguists tend to concentrate because they are more systematic and deep-rooted” (Rickford, 1997, p.1).

Is Ebonics just “slang,” as so many people have characterized it? No, because slang refers just to the vocabulary of a language or dialect, and even so, just to the small set of new and (usually) short-lived words like chillin (“relaxing”) or homey (“close friend”) which are used primarily by young people in informal contexts. Ebonics includes non-slang words like ashy (referring to the appearance of dry skin, especially in winter), which have been around for a while, and are used by people of all age groups. Ebonics also includes distinctive patterns of pronunciation and grammar, the elements of language on which linguists tend to concentrate because they are more systematic and deep-rooted. (Rickford, 1997)

We also read “From Africa to the New World and into the Space Age: An Introduction and History of Black English Structure,” a chapter from Geneva Smitherman’s 1977 book Talkin and Testifyin: The Language of Black America. Her discussion of the grammar structure of Ebonics led to a wonderful day of conjugating verbs. For example, we discussed the absence of a third person singular present tense in Ebonics (example: I draw, he draw, we draw, they draw); students then conjugate verbs using this grammar rule. The zero copula rule — the absence of is or are in a sentence — provided another model for students to practice. Smitherman gives as an example the sentence, “People crazy! People are stone crazy!” The emphasis on are in the second sentence, she points out, intensifies the feeling. I asked students to write zero copula sentences, and we shared them in class.

Empowered by Linguistic Knowledge

After I started teaching my students about Ebonics, many of them began to understand how assumptions about the supremacy of Standard English had created difficulties in their education. One student, Kaanan, wrote,

When I went to school, teachers didn’t really teach me how to spell or put sentences together right. They just said sound it out, so I would spell it the way I heard it at home. Everybody around me at home spoke Ebonics, so when I sounded it out, it sounded like home and it got marked wrong. When I wrote something like, “My brother he got in trouble last night,” I was marked wrong. Instead of showing me how speakers of Ebonics sometimes use both a name and a pronoun but in “Standard English” only one is used, I got marked wrong.

Another student, Sherrell, said,

I grew up thinking Ebonics was wrong. My teachers would say, “If you ever want to get anywhere you have to learn how to talk right.”… At home, after school, break time, lunch time, we all talked our native language which was Ebonics. Our teachers were wrong for saying our language wasn’t right. All I heard was Spanish and Ebonics in my neighborhood. They brainwashed me at school to be ashamed of my language and that almost took away one of the few things that African Americans had of our past life and history.

Throughout the Ebonics unit, I asked students to listen and take notes and see if they could spot the rules of Ebonics at work in the school halls, at home, or at the mall. To celebrate and acknowledge a language that so many of my students spoke without awareness, I pointed out Ebonics in class as students spoke. Often, they didn’t hear it or recognize it until we held it up like a diamond for them to examine.

One day my student Ryan handed me an unexpected gift when he asked if I’d ever heard the rapper Big L’s song “Ebonics.” I confessed my ignorance, but I looked it up on the web and downloaded the music and lyrics. The song is clever, but because the performer misunderstands Ebonics as slang, he provided a great audience for my students to rehearse their arguments about Ebonics. In one essay, for example, Jerrell wrote,

“Ebonics is slang shit,” rapper Big L said in his song titled “Ebonics.” In this song he tells a lot about the slang that young African Americans use, but this is the problem. He is talking about slang; there is no Ebonics in his lyrics. The misconception people have is that slang and Ebonics are the same thing. The problem is that slang is just a different way of saying things. For example, in his slang you say money, you can also say bread, cheese, cheddar, cash, dough, green, duckets, Washingtons, chips, guap, and many more. However, when you use Ebonics, there is a sentence structure that you have to use. Don’t get me wrong, slang and Ebonics go together like mashed potatoes and gravy, but there is a difference between the two. As my classmate said, “Slang is what I talk; Ebonics is how I speak it.”

In his end-of-unit reflection, Jayme wrote that he appreciated “the knowledge that was given to us about the language that we speak and how it related to our roots in Africa.” Hannah wrote, “Kids who have been taught that the way they speak is wrong their entire lives can now be confident.” And I love the sassiness of Ryan’s conclusion: “Ebonics is here to stay and shows no sign of fading away in either the black or white communities. In the words of Ebonics: ‘It’s BIN here and it’s ’bout to stay.'”

Inclusive School Communities

When I took students to local universities to share their knowledge about language during our take-it-to-the-people project, Jacoa told aspiring teachers at Portland State University, “On my college application, I’m going to write that I’m fluent in three languages: English, Spanish, and Ebonics. Call me if you need more information.”

As educators, when we talk about building inclusive communities in which all students can learn, we must also examine how our policies and practices continue to shame and exclude students in ways that may not be readily apparent. We signal students from the moment they step into school, whether they belong or whether we see them as trespassers. Everything in school — from the posters on the wall, to the music played at assemblies, to the books in the library — embraces students or pushes them away. Approaching students’ home languages with respect is one of the most important curricular choices teachers can make.

References

LeClair, T. “‘The Language Must Not Sweat’: A Conversation with Toni Morrison.” New Republic 21 Mar. 1981: 25-29.

Rickford, J. R. (2008). www.stanford.edu/~rickford/papers/SuiteForEbonyAndPhonics.html

Smitherman, G. (1977). Talkin and Testifyin: The language of black America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Smitherman, G. (1998) “Black English/Ebonics: What it be like?” The real ebonics debate. Milwaukee: Rethinking Schools.

Rickford, J. R. & Rickford R.J. (2000). Spoken soul: The story of black english. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

In my Rethinking Schools article “The Politics of Correction” (Vol. 18, No. 1), I discuss more fully how I address moving students between their home language and the language of power, Standard English.