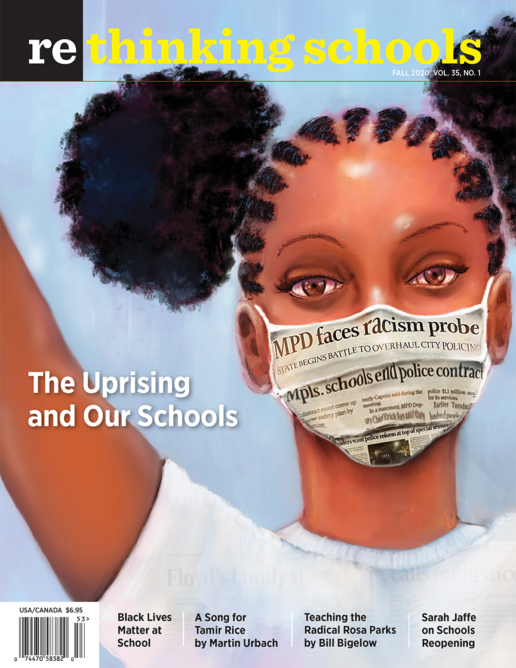

Protesting Pipelines

Teaching the Indigenous-Led Movement Against Fossil Fuel Infrastructure

Illustrator: Nicolas Lampert

There is something about oil and gas pipelines. The way you can look at a map of hundreds of thousands of miles of the terrible tubes, seeing how tightly the thick web of fossil fuel infrastructure has gripped the lands where we live.

The way the technology is so basic, so simple. Just a cylinder — like a child’s straw but bigger — through which the toxic stuff gushes, from one place to another.

Given the pure physical immensity of fossil fuel infrastructure in North America, one would think pipelines would be a more prominent fixture of our consciousness and curricula. And yet, like so many forms of exploitation of the Earth and its living creatures, they can be hard for many of us to see — and are often made harder to see by their manufactured invisibility in the official curriculum. Like the tiny particle toxins industry spews into our air and water, the predatory fine print on a home loan, or the undocumented slaughterhouse worker whose COVID-19 infection shows up nowhere in official statistics, pipelines are purveyors of injustice that don’t usually make the headlines. But pipelines, particularly for the people who live in their path, are right there, running through that wild rice marsh, under that river, across that farm, alongsiwde that reservation. Obvious, touchable, tangible, visible.

And what is visible is vulnerable — to resistance, rebellion, sabotage, and disruption. And vulnerable to exposure in the curriculum.

#NoKXL. #StopLine3. #NoACP. #NoJordanCove. #NoMVP. #NoTAP. Pipeline resistance, led largely by Indigenous people, is happening all over this country and our world, and our students deserve a curriculum that bears witness to this growing movement, and gives them an opportunity to critically reflect on their place in it.

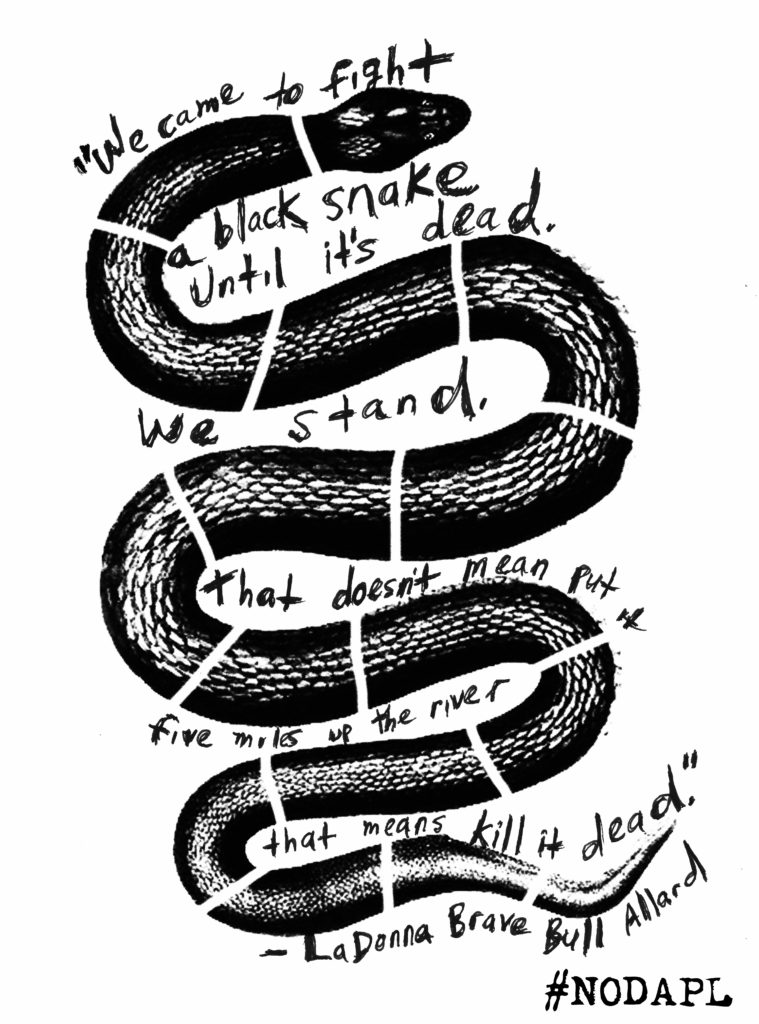

In 2016, when Energy Transfer Partners began work on the Dakota Access Pipeline, the $3.8 billion, 1,172-mile conveyor of half a million barrels of oil a day, across four states and under two massive rivers, the Missouri and Mississippi, some Indigenous people said it was the Zuzeca Sapa — the Great Black Snake. In a Lakota prophecy, the Black Snake would slither across the land, poisoning water and sacred sites before devouring the Earth. But as historian Nick Estes, a citizen of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe, writes, “While the Black Snake prophecy portends doom, it also sparks hope.” In order to defeat the Black Snake, to protect the Earth, a movement was born:

Youth runners from Standing Rock led grueling hundred-mile and then thousand-mile runs to spread the word of the Black Snake threatening their homelands. Thousands, and then millions, answered the call. “City by city, block by block, we stand with Standing Rock!” “Tell me what the prophecy looks like, this is what the prophecy looks like!” “Mni Wiconi! Water is life!” These were the chants that ran through city streets across the world and on the isolated county and state highways of what is currently North Dakota.

While the United States’ expropriation of Sioux land — without which DAPL could not have been approved — is an old story, what felt new about the #NoDAPL resistance camps at the confluence of the Missouri and Cannonball rivers was the scope of solidarity. With between 1,000 and 3,000 Indigenous and non-Indigenous permanent camp residents during the late summer of 2016 and the winter of 2017, more than 300 tribal nations opposed the pipeline, and statements of solidarity came from all corners of the globe. Social media lit up with #NoDAPL campaigns that garnered millions of likes, clicks, signatures, and donations. After initially being covered only by Unicorn Riot and Democracy Now!, the uprising became too large to ignore, garnering critical ink on the front pages of even the most mainstream of mainstream media.

Years later, and still very much in the midst of the fight against DAPL, Standing Rock now stands as a kind of template for activists, a model of what is possible. Again, historian Nick Estes:

If there is a lesson to be learned from the historic movement that began at the Standing Rock Indian Reservation to halt DAPL, it is that great men don’t make history. Presidents at the helm of a white supremacist empire will not save us or the planet. That much is sure. Nor do they, as individual men, doom our collective fate. The good people of the Earth have always been the vanguards of history and radical social change.

There are five key tasks of an anti-pipeline curriculum. It should:

1. Highlight the place of the current protests in a longer history of Indigenous resistance to settler colonialism, and give lie to the myth that “All the real Indians died off.”

2. Place pipelines into the context of a larger climate justice movement. The framework of justice pushes us to not just address the short-term dangers of pipelines (spills, leaks, contamination of land and water), nor only their long-term threat as conveyors of the fossil fuels that are scorching our globe and its living creatures, but also as a manifestation of a larger system of exploitation of the land and its peoples that here in the Americas dates back as far as 1492 and up to the present. Climate justice argues not just for an end to pipelines, but also an end to a system of settler colonialism and racial capitalism — and reaches out toward a more just set of relationships, a more just world.

3. Challenge our students to reflect on their relationships — to each other, the land, water, and animals, those they cherish and those they would like to see transformed. As Estes writes, “For the Oceti Sakowin, the affirmation Mni Wiconi, ‘water is life,’ relates to Wotakuye, or ‘being a good relative.’ Indigenous resistance to the trespass of settlers, pipelines, and dams is part of being a good relative to the water, land, and animals, not to mention the human world.” Let’s ask our students: What does it mean to be a good relative? A good ancestor? And what is the appropriate response to those who are breaking the sacred bonds — and rules — of kinship?

4. Upend standard civics education. The traditional civics curriculum asks students to become experts on a set of already-created laws and institutions, rather than the authors of a new regime of rules and principles. Those old laws and institutions have not protected the Earth and water that our students will inherit. Our curriculum should affirm their right to demand a different future — through organizing, activism, civil disobedience. Indeed, today’s supposed criminals are the ones winning us a right to a healthy tomorrow.

5. Help students see the connections between myriad forms of state violence: the kind that poisons the water, air, and climate; the kind that uses its military and police to wage “a heavily armed, one-sided battle against some of the poorest people in North America to guarantee a pipeline’s trespass”; the kind that keeps 40 million people in the United States living in poverty and many more precariously close to it; the kind that murders Black people by putting its knee on their necks and tear-gases and pepper-sprays them when they protest.

Although there is much work still to be done to produce an anti-pipeline curriculum that meets these ambitious goals, the Zinn Education Project’s Teach Climate Justice Campaign offers some key places to start. A role play I co-wrote with Rethinking Schools curriculum editor Bill Bigelow and high school teacher Andrew Duden on the Standing Rock uprising offers students key background on a pipeline whose future is still up for grabs and ripe for study. While oil is currently gushing through the Dakota Access Pipeline, recent court rulings affirm the Standing Rock Sioux tribe’s long-standing contention that the project was not properly permitted — permits that students learn about in the role play — and should be immediately shut down. Also available to educators through the Zinn Education Project website is Necessity: Oil, Water, and Climate Resistance, a new film directed by Jan Haaken and Samantha Praus. Focusing heavily on the fight against Enbridge’s Line 3 in Minnesota, the film profiles “valve turners” committing civil disobedience, the lawyers who defend them, and the Indigenous activists whose lands are most imminently in danger. The film is a powerful vehicle for students to analyze the efficacy of different strategies of political activism and for considering the roles of uniquely positioned individuals (race, class, gender, ability, citizenship status, etc.) in a collective struggle.

The existential threat posed by the climate crisis compels us to design curriculum that is relevant to the moment, responsive to our students’ fears, and inspires the understanding that change is possible through action. As the movement against fossil fuel pipelines grows, our classrooms can become pipelines for justice, moving the hopeful and necessary stories of climate activism out of the shadows of the official curriculum and into the light.