Prizes as Curriculum

How my school gets students to “behave”

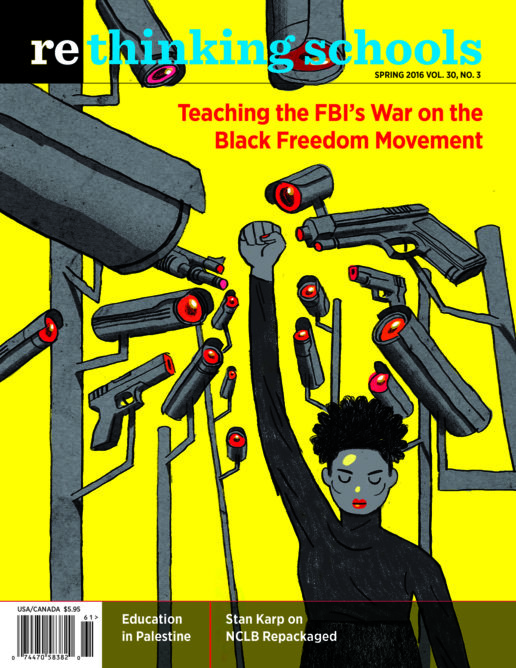

Illustrator: Annette Elizabeth Allen

On the first day of school, the children in my upper elementary school classroom were initiated into the new teacher’s classroom management system. Although he had not planned one academic activity for the day, Dan watched the students carefully for behavior that he could use as an example. The stickers first came out while he was giving a speech about how things were going to change from the previous year. José and Avery were looking through their new pencil boxes. Dan stopped what he was saying.

“I’m going to go around and give everyone who is listening a sticker,” he announced. He started peeling stickers off the sheet and placing them onto empty grids taped to each child’s desk. José and Avery slowly put their pencil boxes back in their desks. Their faces were frozen. The other kids looked stunned. A few of them tried to look excited about their stickers, but their smiles were forced. The room was silent as Dan finished giving stickers to everyone but José and Avery. He explained that once students finished a whole sticker chart, they could choose a special prize or outing. The rest of the day was the same: the children’s every move watched and then rewarded or not in a phase of the sticker program that Dan called “creating buy-in.” The atmosphere in the room was one of confusion and dejection.

The year before, our previous classroom teacher used a reward system that was different in some regards, but the same in essence. The children were given points at several junctures throughout the day for their behavior goals. They were able to “spend” those points in the classroom “store,” choosing candy and toy prizes from the bronze, silver, or gold bin, depending on how many points they had earned. This point system was less public and shaming, but still based on rewarding behavior with “prizes” that could be spent like money.

After Dan’s buy-in period was over, the stickers came out less often, but they were still there. For the students, the shock wore off, but the public shame, the divisiveness amongst children, and the attachment of children’s worth to their behavior were there all year long.

Evergreen Day School is a private school for children whose public school has deemed their behavior too difficult to deal with in a regular classroom. I have been a paraprofessional here for two years. During that time, I have seen how reward systems are not a neutral “tool.” They replicate an economic system where wages, piecemeal pay, commissions, and other performance-based prizes are given to incentivize people to do work they didn’t choose, don’t control the conditions of, and don’t find meaningful. In other words, a system where external rewards are necessary because intrinsic rewards are, for so many people, basically nonexistent. Children who toil in school filling in blanks and bubbles mirror the waitress at Applebee’s who cannot afford to feed her own children or the housecleaner who does not have a house of her own.

Students who live in poverty are most likely to experience empty work, both in school and out. They are hit the hardest with skill-drilling, testing, and tracking. Evergreen serves poor students whose anger at the world is so deep that they lash out violently in school, and the teaching that I have seen here is the worst of this drill-and-kill kind of training. Too often, compliance is the primary curriculum.

For example, last fall, the students in my classroom launched into their first social studies unit—state history. Surrounded by artifacts of this history, what an exciting and interactive unit this could be! And yet—in a state rich with Indigenous history, with the legacy of the Underground Railroad—the unit consisted entirely of looking up state symbols and colonial history dates on Wikipedia.

Or, in May: “We already did this unit! We studied this last year with Louisa!” the kids shouted as Dan announced which chapter of the textbook they would be reading.

“This should be easy then,” he said as he passed out the books.

Over and over, I have seen teachers ignore children’s natural curiosity and interest in learning about the world. For whatever reason, they are reluctant to let students’ experiences and feelings—the intensity of which is constricting their ability to move forward—become a door to learning. Instead, they use prizes to buy compliance. And, to be truthful, the kids love the prizes. For many students, rewards mirror the television, junk food, and other material pacifiers—more easily attained than things like adequate housing, healthcare or childcare—that poor people are forced to turn to in a world where meeting basic needs is a constant struggle.

The Myth of “Good Choices”

“Doing the right thing” at our school is based on standards of obedience that are nearly impossible for my children, who are doing their best under difficult circumstances. “This is your fault,” is the subtext of the refrain. Contrary to the popular narrative at Evergreen, children are left with very little choice in a system of rewards. Their choices are to do exactly what the teacher wants and receive empty praise, or to go against what the teacher wants and be publicly shamed when they do not receive the reward. The teacher makes the real choices, and those choices are based on behavior that teachers themselves have learned from a hierarchical and exploitative system.

The common philosophy of student behavior amongst staff at Evergreen is that students may have difficult lives, but they can “choose” to act appropriately. I once sat in in-school suspension with Nicole. She did her work diligently until she got to her math, at which point she got angry, crawled under the table, yelled, and eventually started throwing books across the room. I tried all of my strategies: being firm, coaxing, ignoring. Neither our generally good relationship nor the unpleasant consequences of her behavior had any effect on how she acted. This is because it was not just the two of us in a room. It was she and I and the history of how teachers treated her at Evergreen and at public school, of seeing her mother arrested in their home several years earlier, of having to live with her sick grandmother, and of whatever other trauma had been inflicted on her family. Her history could not be erased or reconciled with stickers or candy.

What Nicole needed was to feel she had some control over her environment. And, in fact, her behavior turned around when she was able to create her own behavior plan. That plan wasn’t about compliance—it was about letting Nicole have some power over her own life. Rewards deny children the opportunity to reflect on their behavior with the help of adults.

Part of the “good choices” schema is the myth that ideas about correct behavior are objective, not subjective—that there is a “right thing” that should be clear to all. For example, one cold March day three years ago, my class was scheduled to go on a sledding trip. Before we went out, the kids had choice time. Almost zero planning had been done for the day, and it was left up to the students to fill that time. After lunch, for the second time that day, the students had “quiet choice time” in which they played cards and board games, used clay, and did beadwork.

Eric, a 4th grader, had finally had enough of entertaining himself. He decided to sit quietly at his desk and wait for choice time to be over. A power struggle ensued between him and Louisa, the classroom teacher, because his choice for choice time was unsatisfactory to her. When Louisa informed Eric that the consequence of not choosing an activity was not going sledding, Eric got angry and refused to leave the room. In the end, Louisa and I took the class outside and left three male staff alone in the room with Eric. After a little while, I heard a crash and later learned that Eric was provoked into such anger that he had thrown a desk and swung a punch at a staff member. The men restrained him and dragged him out of the classroom.

Eric lived with his mother, stepfather, and three siblings. He had recently lost contact with his father due to his father’s aggressive behavior. His mother worked nights as a nurse at a hospital two hours away. That summer, the family had been evicted from their home. Although he struggled with academics, Eric had a deep curiosity about the world and was quite astute. One day a few months earlier, I heard him say to the classroom assistant that we didn’t do anything academic at this school, and that his mother thought that too, and she didn’t like it. He was right, of course, but the classroom assistant told him that it was “too bad” that he thought that.

I remembered that conversation when Eric was denied the sledding trip because it shows two opposing perspectives in the room: Eric’s innate desire for intellectual challenge and his frustration at being ask to sit still and follow directions without stimulation or inquiry. And Louisa’s perception, despite her failure to provide the students with meaningful learning experiences, that Eric’s boredom was his problem.

Louisa was a warm and well-meaning person. After this incident, she wanted to reflect on what had happened—it had been an upsetting day for all. Louisa asked herself certain questions and didn’t ask others. In the end, she was able to justify her decision in a way that enabled her to see her decision as a moral one. “Eric has problems entertaining himself, and that’s something we need to support him with. Maybe something is going on at home,” she sighed.

“Good” Tokens and “Bad” Tokens?

Reward systems are not unique to Evergreen. Innumerable schools around the country use reward systems to entice kids to behave. I understand why teachers want to use them. The pressures of reforms that push skill-drilling and test scores make it more and more difficult to manage restless and hurting students. Sitting quietly and listening may seem irrelevant or impossible to a student who has no running water or who cannot afford nourishing food. Well-meaning teachers are left to deal with the contradictions of hunger and test prep, of “student-driven” learning and students who have been given the message that they cannot learn. Teachers, as well as students, are backed into a corner and rewards can make classroom management in this environment much easier.

In the local public school district that supplies Evergreen with students, most of the elementary schools use Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS). PBIS is a national program centered on reinforcing “positive” behavior. If we question the things that happen at Evergreen, we should also question the reward system in PBIS.

The framework underlying the rewards systems at Evergreen is behaviorism, the idea of shaping human behavior based on external rewards and punishments. PBIS is a more nuanced program with many different facets for affecting student behavior.

The PBIS website states that it will “maximize success for all students” and increase “instructional time.” Many colleagues in the local public schools have noted what an important shift it has been to focus on positive behavior instead of negative. It is certainly a big improvement from zero-tolerance behavior policies. However, it too uses aspects of behaviorism in its token reward system: Teachers, once again, are encouraged to dole out tokens for good behavior.

I have had countless conversations with colleagues whose schools use these reward systems. Certain themes re-emerge. Teachers say that students with the hardest lives and the most difficult behavior are beaten down the most when their behavior is judged with tokens. A friend who is an assistant in a preschool classroom in a school that uses PBIS described to me how she was instructed to give a special needs student treats at intervals throughout carpet time to encourage him to sit still. She described how upsetting it was “that he was treated like a dog.”

Then again, in order to make the tokens mean something, they cannot be given equally to every student. Inherent in the system is that certain students do not receive tokens. So, inherent also is individualism and competition; children are divided and pitted against each other just like they would be in any exploitative situation.

In fact, rewards distance all of the relationships in a classroom, especially those between teachers and students. What our students (and we) crave is human connection. Our relationships are the heart of our classrooms. Yet, instead of a conversation, a hand on the shoulder, a word, a look—students are given a token. Like a slot machine: stickers in, correct behavior out.

“Worry about yourself” and “mind your own business” are refrains that I hear incessantly at my school. When kids are dragged off to the “break room,” the padded cell we have for children who become violent, the others are told to carry on with what they are doing. Human relationships, especially the way that teachers treat children, are inescapable lessons of every education. They occur regardless of whether or not they are written into the Common Core standards. Watching a classmate being carried kicking and crying to a padded room and being told to ignore it is a lesson.

Connection vs. Classroom Management

At the root of the problem with rewards systems is the dichotomy between “instructional time” and “classroom management.” The rhetoric implies that “instructional time” is something that happens when students are “behaving” and that somehow the actions of students and teachers in the classroom are separate from the content being taught.

The chasm between children’s lives and the content of most curriculum is a chilling marker of how the standardization of education treats humans like programmable machines. In a world where kids are hurting so deeply that they are lashing out violently, what bigger hope can we instill than to help them analyze their behavior in the context of history and the world, so that they feel less alone, less like “bad” kids? This, to me, is instructional time.

How do we, as educators who see our role as part of creating a more just world, address the violent, angry, and unproductive behavior that occurs in our classrooms? We have to start with the content of our curriculum. How does it touch our students’ lives? I think about the child of color in my class who, after a role play of a lunch counter sit-in (one I led with a small group), wrote to me: “I felt like I was getting in trouble, but I knew it.” In this moment, a doorway was opened to talk about resistance as a conscious, tactical choice, an opportunity to discuss different kinds of resistance, where they come from, and what impact they might have.

Even content that isn’t explicitly “social justice” can lead to moments of deeper connection. One day, as my students wrestled with their unsuccessful attempts to paint the sunsets they had envisioned in their minds, I tried to connect the frustration they were feeling to other moments of struggle in their lives. I wanted to help them see beyond the surface frustration. Unfortunately, I have seen teachers in similar situations walk around and give candy only to children who were not having a hard time. Although it does not provide instantaneous classroom control in the way that giving prizes does, ongoing conversations help students contextualize and reflect on their behavior. Thoughtful, empathic discussions are part of the long road to helping students make decisions about how they will act in the world instead of manipulating them with rewards or letting them react to unjust situations with the unproductive violence that is used to justify the imprisonment of so many young people.

Of course, even the most relevant and meaningful education cannot counteract all that happens in students’ lives. Even the best teachers have to deal with hurtful and destructive behavior. But the best teachers try to feed hungry minds and nurture damaged souls. Some may be quiet and soft-spoken, and some may yell, but teachers who love their students and want to use teaching to create a better world oppose behavior in their classrooms that arises from and perpetuates exploitative systems.