Preview of Article:

Peers, Power, and Privilege

The social world of a 2nd-grade classroom

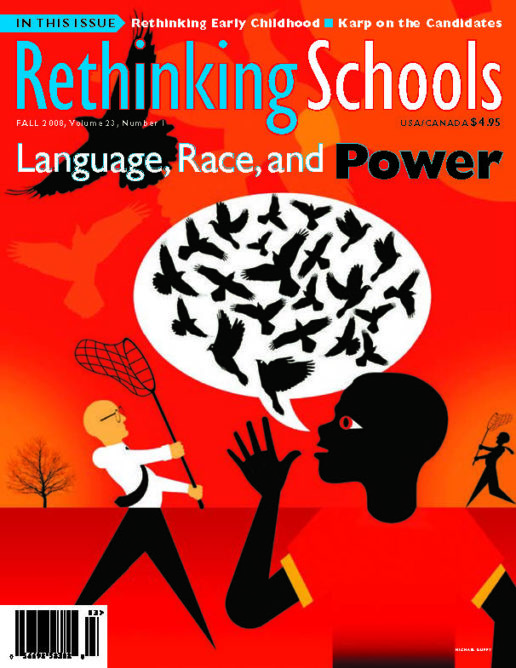

Illustrator: Alain Pilon

I vividly remember standing at the door of my classroom on the first day in my new school, a highly regarded urban magnet school. I was 8 years old, and I looked around at my classmates — they were so different from those at my old private school where everyone had pretty much looked like me. Here were kids with a wide variety of skin colors, hairstyles, and clothes. I wanted to throw myself into the classroom and become friends with them all!

Unfortunately, it did not turn out that way. There were confusing barriers. I remember one day on the playground walking over to a group of black girls and watching them play a hand game that was unfamiliar to me and listening to them talk, using many words that I did not understand. I hovered for a while, hoping that someone would invite me in, but I felt awkward and invisible and slowly walked over to the other side of the playground where a group of mostly white kids were playing games that I did know.

Gradually my circle of friends (all girls) coalesced and included four white girls, one biracial (Puerto Rican/white) girl, one black girl (often teased by other black kids, who called her an “oreo”), and a child from India. What I did not realize at the time was that they were all from middle class families. Our families lived in similar neighborhoods; our parents became friends. For the kids, it translated into frequent play dates and carpools to gymnastics and soccer, places where I never saw my classmates from low-income families.