Peacekeepers and Peacemakers

Fifth graders explore what we do when peace doesn’t already exist

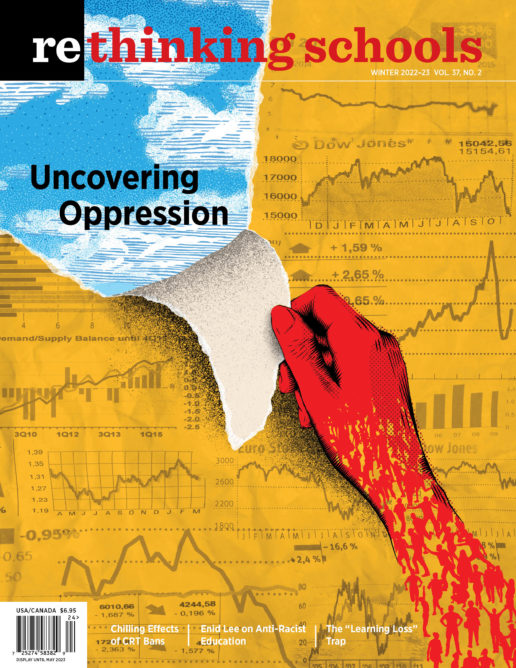

Illustrator: Sophia Foster-Dimino

I looked across the school cafeteria, coffee in hand, and watched as my 5th-grade students gathered alongside the rest of the elementary school and repeated our daily litany of pledges.

At just 7:50 a.m., students were already in the middle of their third pledge of the morning.

After the U.S. Pledge of Allegiance, students recited the Pledge to the Texas Flag, and then moved on to our school pledge, which the school had proudly named (or rather, adults far removed from the classroom had named) the Peacekeeper’s Pledge. On this morning, it was the Peacekeeper’s Pledge that really caught the attention of my still-awaking brain. What were our students promising to do? Who were they promising to be? And why did we expect them to mindlessly recite words that they had played no role in creating?

The students wrapped up their pledges, essentially promising to be obedient students for the day, and then we walked down the outdoor hallway to our portable. As students chattered about video games and their activities from the night before, I kept thinking about the Peacekeeper’s Pledge.

Students hung up their backpacks outside the classroom and came inside to sit in a circle on the carpet for our morning meeting. We went around the circle for our sharing time, and then once each student had the opportunity to share, I broached the subject with the class.

“I’ve been thinking a lot about the morning pledges. What are pledges? Why do we say them?” I asked.

Jeremiah raised his hand and suggested, “Like a promise? I think the pledges are like promises.” Others nodded in agreement.

“Yeah,” Joaquin added. “It’s like we promise to do those things.”

“OK,” I said. “Promise is a good word. So I’m wondering then, what exactly are you promising to do? Specifically, when you say the Peacekeeper’s Pledge, what’s the promise that you’re making?”

Aliyah raised her hand. “I think the Peacekeeper’s Pledge is kinda like the school rules. We promise to follow the rules.”

I affirmed Aliyah’s contribution and suggested that we take a closer look at the school pledge. I took down our copy of the Peacekeeper’s Pledge from the wall, and we read it together. This time, though, I encouraged students to read it slowly and thoughtfully, and to really think about the words, instead of just repeating them. The pledge read:

I am a Carver Elementary Peacekeeper.

I promise to be helpful, truthful, and kind.

I promise to respect my teachers, parents, and friends.

I promise to solve problems with my words.

I promise to always do my best.

You can put me to the test.

I am a Carver Elementary Peacekeeper.

After reading, my students shared some of their thoughts. Their comments were mostly positive, that these were good rules to follow and it’s good to work hard and be kind to people. Some students were annoyed that they had to say so many pledges every morning, but no one had an issue with the content of the pledge.

How could we ask students to promise to “keep the peace” in the midst of injustice?

I, on the other hand, was puzzling over how this school pledge, and others like it, prepare our students to engage with issues of injustice. How does promising to “respect our teachers, parents, and friends” prepare students to engage in local and global activism? And while being “helpful, truthful, and kind” are typically great character traits, what about situations in which kindness isn’t enough? In the midst of police violence, white supremacy, and a violent presidency, the refrain “no justice, no peace” repeated in my head. How could we ask students to promise to “keep the peace” in the midst of injustice? This pledge did not push my students toward the justice orientation I hoped they would take up, nor did it provide them with tools for engaging in collective action.

So I pushed them further.

“I agree with you, I think these rules are helpful in a lot of ways,” I said. “I think it’s good to be helpful and kind and to do your best. But here’s what I’m struggling with. I think the Peacekeeper’s Pledge is great if we live in a 100 percent fair and just society. If peace already exists, we should definitely work to maintain it. But what do we do when the peace does not already exist? I’m not sure this pledge is very helpful in making peace.”

Internally, I had a vision of peace that was not congruent with the state of our country, and was especially incongruent with the realities of my Black and Brown students and their communities. When I think of “peace,” I think of contentment, tranquility, and a space void of conflict in which every person is free to be their authentic selves and to live in harmony with others. This vision of peace is what every community wants and deserves, but it is a utopia that is not a reality for marginalized and underserved communities. There is an underlying assumption of equal rights that is foundational to a peaceful society, and without justice, peace can only be a reality for those benefiting from the current system.

Our morning meeting time was limited, and on this first morning we didn’t dive much deeper into the issue of the pledges and my wrestling with peace and justice. I had wanted to share my interest with my students, and to get them thinking critically about the words they were saying. But I knew that this would not be the end of our conversation around pledges, and I started making a plan to return to the topic. I wanted us to start thinking about what it might mean to get into trouble, “good trouble” as the late John Lewis so eloquently described it, for the sake of justice. A guiding question was coming into focus for me: What do we do when the peace does not already exist?

How did leaders like Nelson Mandela, Frederick Douglass, and Malcolm X fight for their communities’ rights to live in a peaceful society in the midst of violence and oppression? For each of these individuals, and many more like them, fighting for their communities meant disrupting the “peace” that those in power already enjoyed. These individuals did not “keep the peace,” but rather, they actively disrupted the status quo, sometimes through engaging in violence. They did not fit the bill for “peacemakers,” and yet, their fights for justice pushed for marginalized communities to experience the peace and the privileges that those in power already enjoyed.

I went home that evening and began designing an exploration into peacekeepers and peacemakers. I searched through picture books and online resources, looking for historical and contemporary figures who worked to make peace when the peace “did not already exist.” I looked for women, people of color, and people historically pushed to the margins — people who had just reasons to break unfair rules.

Only in my second year of teaching, I didn’t have a wealth of information and resources at my fingertips. I was dedicated to teaching toward social justice, and to help my students learn counternarratives surrounding U.S. history, but as a product of the same school systems as my students, I had gaps in my own knowledge. With little variation, the pledges my students recited and the figures they learned about were the same pledges and the same historical figures I had learned about during my own schooling experiences. Seeking out figures who exemplified different kinds of citizenship, figures like the Freedom Riders or Claudette Colvin, who defied Montgomery’s bus segregation before Rosa Parks’ famous action, was not only a way to teach my students a more nuanced vision of history and current events, but I was also teaching myself.

After sorting through a selection of books, I created a text set highlighting figures I identified as peacemakers, people who got into “good trouble” for justice. The picture books from the text set illustrated the stories of historical and contemporary figures whose behavior did not exactly follow the rules laid forth by the Peacekeeper’s Pledge. These were people who broke the rules when they were unjust, and who boldly stood up to power structures and authority figures. They were peacemakers.

I chose to begin our exploration by starting with a story I felt exemplified a fight for justice that required being more than a peacekeeper: For the Right to Learn: Malala Yousafzai’s Story by Rebecca Ann Langston-George.

“These people might challenge the idea that following the rules is the same thing as being peaceful.”

The next day, I gathered my 5th graders on the carpet. I reminded the class of the conversation we had begun the previous day, and I shared the new books that I had found. Showing my students the covers, I said, “These people might challenge the idea that following the rules is the same thing as being peaceful. As we read about Malala’s story, I want you to keep the Peacekeeper’s Pledge in your mind, and I want you to think about whether she is following the pledge or not.”

I then read aloud For the Right to Learn: Malala Yousafzai’s Story, pausing to think aloud or to invite students to turn and talk to a partner at specific parts.

Through our reading of this picture book, we learned about Malala’s childhood in the Swat Valley of Pakistan, her love for her homeland, and her passion for learning. When the Taliban took over her city Mingora, women’s rights were restricted, and young girls lost their right to an education. Malala bravely defied this ban on education. She continued to go to school and began publishing about life under Taliban rule using the pen name “Gul Makai.” Malala defied unfair rules for the sake of justice and faced incredible violence from the Taliban as a result. Despite the violence she faced, including being shot, Malala has continued her activism and remains outspoken in the fight for women’s education today.

After closing the book, I turned to the class: “So I wonder, if we agree that Malala wasn’t being a peacekeeper in this book, what was she being? Was she being a troublemaker?”

“She wasn’t a troublemaker! She did the right thing!” Jeremiah called out, steadfast in his conviction that Malala should not be branded with a negative label like troublemaker.

“She did get in trouble though,” I argued. “She was even shot! That wouldn’t have happened if she just followed the rules and obeyed the people in power.”

Anahi chimed in: “I mean, yeah, she got in trouble, but she got in trouble for doing the right thing! She wasn’t the troublemaker. She was brave.”

“I agree that she did the right thing,” I responded, “but she also kind of caused trouble, didn’t she? She didn’t really follow the Peacekeeper’s Pledge. She didn’t respect the adults who told her not to go to school. She was told not to and she did it anyway. That was disrespectful to the men who told her to stay home.”

My students pondered the questions. I was complicating their understanding of what it meant to be “good,” what it meant to be a peacekeeper. For years, they had been taught that being good was synonymous with following rules and obeying authority. Proposing that good people sometimes choose to get into trouble brought a new lens into our learning.

“So I wonder,” I continued, “if she wasn’t really being a peacekeeper, but if we don’t think that troublemaker is the right word either, then maybe there’s another category we haven’t talked about. What do you think it might mean to be a peacemaker?” Rather than allowing students to come up with their own term for this category, I provided them with the label peacemaker. I wanted us to wrestle with what it meant to keep or maintain something, versus the difficult work required to make something.

I then drew a big T-chart on the whiteboard, and labeled the left side “peacekeepers” and the right side “peacemakers.” Under peacekeepers, I wrote “keep the peace that already exists.” “What else does the peacekeeper’s pledge ask us to do?” I asked.

“Follow the rules!” Anahi responded, along with a chorus of agreement from her classmates. I wrote “follow the rules” under the criteria for peacekeepers.

“If a peacekeeper follows the rules, then what would a peacemaker do?” I wrote “create peace where it does not already exist” on the right-hand column and asked students to turn and talk to a partner before sharing their responses. Among the chatter, I overheard a disagreement between JJ and Sabrina, and asked them to share their dialogue with the class.

JJ shared, “If a peacekeeper follows the rules, then a peacemaker breaks them.”

“Not every time! You shouldn’t just go around breaking rules,” Sabrina responded.

“You both make really good points,” I chimed in. “I’m wondering if there’s a piece to this that we’re missing. Do you guys think that a peacemaker breaks the rules all the time, or?”

“I think a peacemaker breaks the rules if they’re not fair,” Joaquin jumped in.

I agreed with Joaquin that “if the rules are unfair” may be the important point we were missing, and the class agreed. I added “willing to break the rules when they are unjust” to our T-chart, and we continued our discussion. We eventually landed on three criteria for each.

PeaceKEEPERS

- keep the peace that already exists

- follow the rules

- respect authority

PeaceMAKERS

- create peace where it does not already exist

- willing to break rules when they are unjust

- willing to courageously stand up to authority for the sake of justice

Continuing the Work

After this initial read-aloud, we continued our exploration throughout the next few weeks. We read a picture book about John Lewis and analyzed his quote that inspired so much of this unit: “Get in trouble. Good trouble. Necessary trouble,” and students became familiar with the idea of “good trouble.”

Students read books on different figures, such as Claudette Colvin, the Freedom Riders, John Lewis, and Fred Korematsu, and created biographical posters of the figures, in which they described whether the figure they researched was a peacekeeper or a peacemaker, and why. We began to ask, “What kind of ‘good trouble’ did that person get into and why?”

While the curriculum began to transform as we centered peacemakers, we didn’t stop learning about peacekeepers, either. We learned about both side by side, and discussed the hard choices that people make in the face of oppression and discrimination.

In one instance, we read Goin’ Someplace Special by Patricia McKissack, a picture book included in our standardized curriculum. This book tells the story of a young Black girl who experiences multiple episodes of racism while on her way to the town library. In each instance, the young girl does not speak up or act out in response, and instead waits patiently to arrive at her favorite place, the library. Instead of just answering the comprehension questions provided by the curriculum, (which did not address the character’s responses to racism), we also talked about why this character chose not to make trouble in this moment, asking questions like “What was she risking? Who would be impacted by her actions? What did she have to gain or lose by her different responses?” We discussed her choices, the potential reasons behind her choices, and how the story would be different if she were acting as a peacemaker in the story instead.

At each point of our learning, I hoped to include the nuance that people can choose to be peacemakers in some situations, and peacekeepers in others. My intentions in teaching about peacemakers were not to teach students to disregard authority and to break all the rules. To the contrary, my intention was to teach students to think critically about when it is most fair and peaceful to obey and follow the rules, and when it is most fair and peaceful to break the rules or stand up to authority. I wanted my students to be able to think about a multitude of settings and conflicts, such as their own families and communities, the playground, our classroom, and the wider context of national and global conflict and injustice. I wanted them to think about the times when it is most appropriate to keep the peace, and when it was necessary to cause a little disruption. I wanted my students to be able to look at a photograph of Martin Luther King Jr. being hauled off to jail, and I wanted them to be able to have words to describe the kind of trouble he was getting into, and why it was worth it.

Bringing a New Lens into the Rest of the School Year

Our lesson on peacekeepers and peacemakers, which began with my own questioning of the pledges we ask students to recite each morning, became a lens that we used for the rest of the school year. In language arts, while we described characters as static or dynamic, flat or round, we also now described them as peacekeepers and peacemakers. During times of conflict, whether on the playground or in the news, we discussed the appropriateness and the cost of being a peacekeeper or a peacemaker in each situation.

Too often, we teach students that being good citizens means personal responsibility: follow the rules, help others when you can, obey your teachers and parents. It would then follow that bad citizens break the rules and disobey. This kind of binary thinking does not provide students with the tools necessary to think about activism and good trouble. My hope is that by providing a framework of peacekeepers and peacemakers, my students can see that there are a wide variety of ways to be a good citizen, and sometimes being a good citizen means breaking a rule and disrupting the status quo.

As the school year came to a close, we gathered on our classroom carpet the way we had every morning since August. As we wrapped up our morning meeting, Joaquin looked at me, and said, “You know, Ms. Green, we’ve learned how to be peacemakers this year, but we still say the Peacekeeper’s Pledge in the cafeteria every morning. Can we rewrite it? Can we have a Peacemaker’s Pledge just for us?”

“I think that’s a brilliant idea, Joaquin,” I responded, along with a chorus of affirmation from his classmates.

I turned to my computer, hooked up to the document camera, and I shared an editable copy of the Peacekeeper’s Pledge. Keeping the spirit and cadence of the original pledge, line by line, we rewrote it together.

I am a Carver Elementary PeaceMAKER.

I promise to be bold, brave, just, and compassionate.

I promise to seek truth, justice, and liberation for all people.

I promise to create peace where it does not already exist.

I promise to always stand up for what is right,

I am a Carver Elementary PeaceMAKER.

The Peacemaker’s Pledge lived only in our classroom, as our larger school community continued to support the recitation of the Peacekeeper’s Pledge, despite my critiques. We didn’t enact a schoolwide change, but we challenged our own ways of thinking, and brought the spirit of peacemaking into our classroom and our approach to living in community with each other.

Rewriting the pledge had not been my original intention, and in hindsight, I wonder about the usefulness of pledges altogether. Although I do believe the Peacemaker’s Pledge held much more meaning to my students as the creators of the pledge, I wonder what we, both adults and children alike, accomplish by reciting any kind of a pledge.

As is typical with any lesson or any school year, I didn’t end with all the answers. I still question pledges, and I still feel conflicted about reciting them. Despite the internal conflict, I do hold tight to two things, both of which we strived for during this unit: the value of opening up space for students to question what is asked of them, and the value of providing students with the tools to advocate for change. l