Preview of Article:

Passion Counts: The “I Love” Admissions Essay

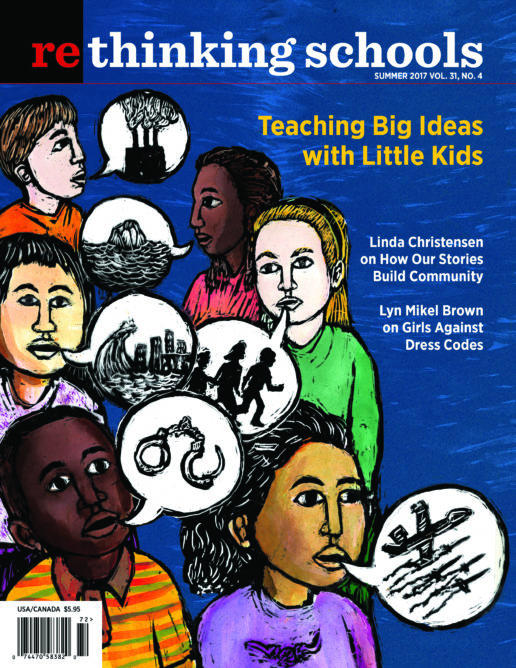

Illustrator: Alaura Seidl

At the heart of social justice teaching is an effort to reorient the curriculum in large and small ways—by examining history from diverse perspectives, by bringing marginalized and silenced voices into the study of literature, and also by helping students rethink who belongs in college. So when my students bump up against their perception of who is “college material” and who isn’t, my job is to use the everyday details from their daily lives to teach them to see their brilliance and their capacity to learn.

Some of my junior and senior students count themselves out of college because they lack the typical credentials like high scores on SATs, a strong GPA, and advanced classes. The repeated litany from counselors and teachers of what it takes to succeed in college creates a hierarchy of experience that teaches some kids to dismiss or devalue the aspects of their own academic lives that don’t align with the common view of who should attend college.

At Jefferson High School in Portland, Oregon, where I have worked in various capacities for four decades, life intrudes in many of the students’ school lives, interrupting their attendance as well as their ability to concentrate and deliver homework. One student’s family was evicted; they lived in a car, then a campground. Another student’s parents both lost their jobs, so he had to drop a couple of classes and start working at a fast-food restaurant to help his family.

But even students without these extreme circumstances have performed poorly in school for a myriad of other reasons: They didn’t see themselves in the curriculum, they were bored by content that didn’t seem relevant, they had other passions that they cared more about.

Before they write essays convincing admission officers to accept them into college, students need to uncover and believe in their own capacity, to understand that when they are guided by their interests and passions, they exhibit the kind of curiosity and attention to detail that leads to success. When they are in places that feel like home—the basketball court or the mock trial court, the dance or art studio, the poetry stage—they exhibit amazing ability to focus and persevere, to practice and rehearse, to harness their attention in ways that will serve them in college or any other pursuit. They need to be taught how their success in these areas can demonstrate their success in another. To help students story their lives so that scholarship committees can see the person behind the statistics, I introduce them to Andrew Kafoury, a Jefferson student who graduated many years ago. Andrew was an exceptionally talented actor whose grade point average didn’t match his stage presence, his nimble-witted brilliance during class discussions, or his ability to write across genres in ways that either convinced us or made us laugh.

During a unit on college application essays, Andrew wrote a passionate piece to win acceptance into a college known for its theater program. He used an unconventional approach: He structured his essay as a letter addressing the head of the program. He opened with a couple of paragraphs describing his first memory in the theater. Then, in a brief paragraph he listed what he wasn’t good at—the list was long. In the center of his essay, Andrew detailed the reasons he loved acting. These paragraphs created a verse poem with a specificity of language about theater that sweeps the reader up in his passion, his knowledge of the stage, his willingness to play any role. His essay ended with his current work and his future dreams (see Resource).

At first, I wasn’t sure if Andrew’s letter would work as a model for college essays because so many prompts today are bound to the common application. But students found ways to weave parts, if not all, of their essays into those prompts. I was also concerned that students’ love of basketball, softball, dance, or music wouldn’t translate into an essay that showcased their academic prowess. But from reading their papers, I discovered that a passion and the willingness to pursue it demonstrate a student’s perseverance and focus. Their essays reveal the dogged determination that gets them up for a 5 a.m. practice, makes them choose rehearsals over hanging out, teaches them how to harness time, and shows that sometimes hard work overcomes perceived lack of talent.