Our Stories: Students Curate the Museum of Corona History

The best teachers that I’ve had are still quiet voices in my head. In college, I took Professor Phyllis Jackson’s art history course “Black Aesthetics and the Politics of (Re)presentation.” The course taught me how to interpret the visual landscape around me in new ways. Professor Jackson taught us to explore how race and intertwined systems of identity and power influence representation in all forms of art. Textbook covers, classical art, and party flyers all became ripe with new meaning. Our final project was to create a museum exhibit; the experience of selecting, displaying, and analyzing works of art for public engagement permanently changed my concept of learning and public space.

As a high school teacher, I seek to recreate the same magic that I experienced with Professor Jackson for my own students. In U.S. history, scope and sequences that called for units on manifest destiny and the American empire were inverted in our classroom to create exhibits on powerful resistors — Indigenous communities, abolitionists, and suffragists — in our Museum of American Power. Field trips to Washington, D.C. included assignments that challenged students to examine the design of public monuments, memorials, or parks and to tell the stories that they believed were missing from our nation’s capital.

This year when the coronavirus outbreak caused my Los Angeles Unified School District campus to move into remote teaching, I asked my students to write or draw what was happening in their lives. One of my world history students, Julieta Littin Egana, wrote a sentence that hit me hard. On Monday, March 16, 2020, our first day of quarantine, she shared, “I feel like this is going [to be] and already is a very big event in history.” The importance of studying history becomes clear when you are suddenly aware that you are living in a moment of great change.

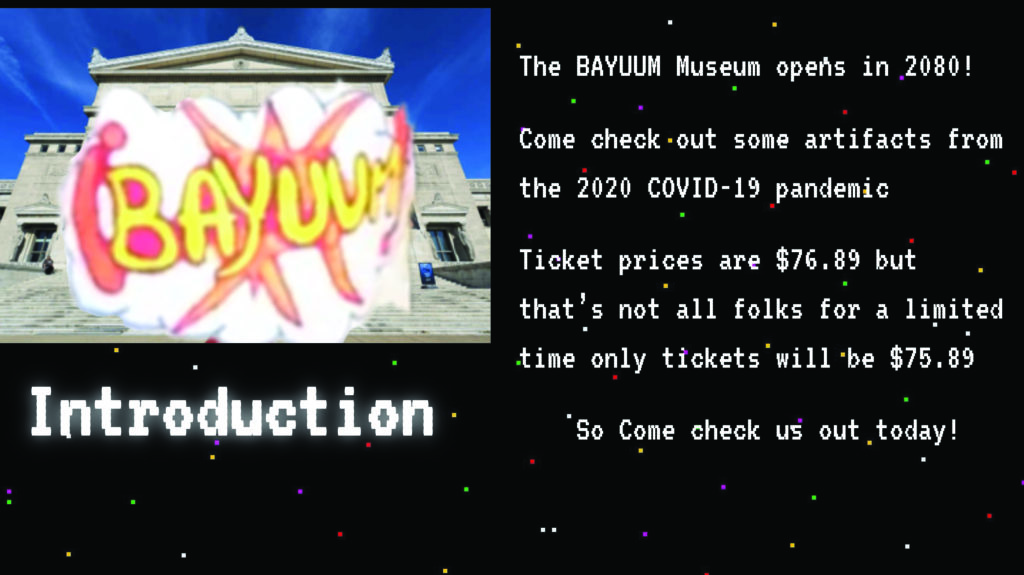

I began to craft an end-of-year assignment in which students would gather and display artifacts for a Museum of Corona History, or MOCH as the students began to call it. MOCH would open in 2080 to share people’s experience of the pandemic of 2020. Each student would include three artifacts: textual, visual, and personal. To better understand the breadth of possible artifacts, we explored artists like Mona Chalabi and organizations like Amplifier Art. We invited guest artists like Jeremy Kaplan to join our Zoom class in conversation about artifacts as an intersection of art, history, and change.

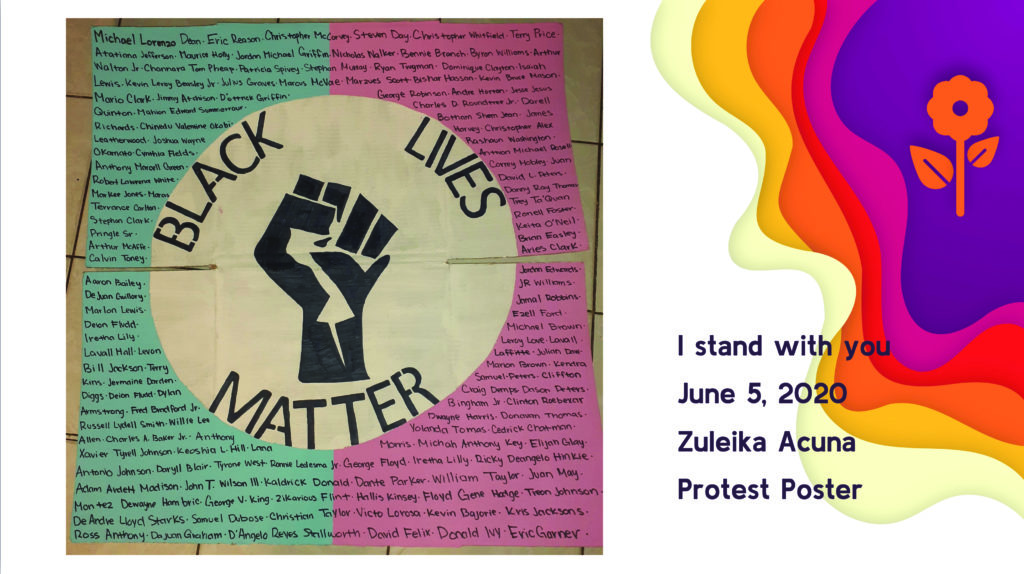

Halfway through our work on MOCH, our nation saw another police murder of a Black person, George Floyd, and the beginning of the 2020 uprising. Our conversations and artifacts began to shift in focus. Again I paused instruction to ask my students to share words or images that describe what was happening in their lives in regard to the police violence and protests that overtook our city of Los Angeles. My world history students have practice studying Black resistance. Toussaint Louverture, the Battle of Adwa, Patrice Lumumba, the Ogoni people, and African Risk Capacity have a home in my course syllabus. When we discussed the Black Lives Matter movement, it was with historical precedence, as well as moral urgency. The changing context of the students’ lives altered their choices in artifacts.

We spent our Zoom classes together in exploration of artifacts in the three categories I had identified for them. Later in our work on the MOCH project, in breakout rooms and sharing out with the whole class, we thought about the collection of artifacts each of us had gathered. Students participated in communal brainstorms and feedback sessions on how a set of artifacts could make a stronger statement cohesively, rather than if each artifact was presented in isolation. As we moved into designing our display of these artifacts we virtually visited museums and memorials to take note of how expert curators create engagement between visitors and objects, craft immersive cultural experiences, educate the public, and powerfully honor public and private loss.

I presented an exemplar presentation the week before the due date, and was quickly outshined by student work. We came together for our final Zoom class to showcase our work via screen-sharing of individual students’ MOCH exhibits and a gallery walk through all of our exhibits through the common hashtag #MuseumOfCoronaHistory on Instagram. In this closing conversation, the personal artifacts stood out. Through PowerPoints, photographs, and screenshots I learned about rough and smooth edges of their lives I had never glimpsed before. How does it change a student to have their entire semester submitted via cell phone photographs? Who are the YouTube celebrities that curate their social life? How can we document our loss, and pay tribute to the creative nooks and crannies that are uncovered?

We are not alone in documenting the evolving context. Historians have begun collections; there’s even a New York University collection of collections. Libraries, such as the Los Angeles Public Library, have started similar efforts with submissions from the public. Renowned national and local museums have begun gathering their own artifacts of the 2020 pandemic. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture has announced an effort to preserve George Floyd protest materials. One hopes that other museums will follow suit. In the pandemic, institutions have begun to reinvent themselves and move into new spaces of possibility. In the Black Lives Matter uprising, institutions must take responsibility for doing so.

The act of historical documentation is an act of power and possibility, especially when undertaken outside of the realms of experts and authorities. What is recorded is remembered. The stories we tell shape our choices, values, and concept of self.

I tell a story in my classroom every year about milk cans. During the Holocaust in the Warsaw Ghetto, Jewish writers, teachers, and rabbis wrote accounts of their community and preserved artifacts of their life. They placed this precious archive into milk cans and buried them under the rubble of what had been streets. I ask my students, how is this a method of resistance? We survey the resistance methods we have studied — when people cannot save themselves they save their children, when they cannot save their children, they save their memory. I ask each class, what would make the resistance of the people of the Warsaw Ghetto milk cans successful? It is my students who make the Warsaw resistance victorious. By remembering these stories 80 years later, my students make the last work and wishes of these people in Warsaw come true.

There is so much tragedy and injustice in human history and in the present. And there is so much more possibility. We must arm and rally our young people with past traditions of resistance and innovation. What can happen when a community tells its own story? How can we tell our stories, not only with each other, but with the generations to come? These are the questions I hope will become quiet voices in my students’ ears.

A version of this article was first published at Monument Lab Bulletin, a collaborative platform for critically reading and reimagining monuments.