Our picks for books, videos, websites, and other social justice resources: Summer 2022, Volume 36.4

Picture Books

“It’s important to remember that we never pick the first blade of sweetgrass we see,” Grandmother says as she teaches her granddaughter Wabanaki traditions of respect and how to identify and pick sweetgrass for basketmaking. When Musquon has trouble telling the grasses apart, Grandmother gently reminds her to look closely at the different grasses and get to know them: “Sit here and take your time. Your ancestors are here with you.” In this picture book, authors Suzanne Greenlaw (citizen of the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians) and Gabriel Frey (citizen of the Passamaquoddy Nation) bring thousands of years of Wabanaki tradition into the present. The back matter, which includes a short Passamaquoddy-Maliseet glossary and an author’s note, states: “The sweetly scented, emerald-green grass holds spiritual, economic, and cultural importance for the Wabanaki and many other First Nations across the continent.” A great read-aloud for early elementary, teachers of older students could pair it with Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass chapters “Wisgaak Gokpenagen: A Black Ash Basket” and “Mishkos Kenomagwen: The Teachings of Grass” to offer additional First Nations’ perspectives and extend discussions of Indigenous knowledge and science.

***

Award-winning children’s book author Carole Boston Weatherford tells the story of Miss Mary Hamilton, whose 1964 Supreme Court case led to the ruling that all people in court should be referred to by their full name. Hamilton was a teacher and the first woman to head the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE)’s southern region. Arrested many times during the Freedom Rides, one day she refused to respond to an Alabama judge who referred to her only by her first name. Sentenced to jail and fined for contempt, she appealed to the state and then to the Supreme Court with the help of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. Miss Hamilton’s insistence that she be referred to as Miss, instead of “girl,” “auntie,” or other demeaning terms, challenged the racism in the use of these names. Illustrator Jeffrey Boston Weatherford weaves archival photographs in with his illustrations, providing historical context to Miss Hamilton’s story. The Weatherfords introduce themes of colorism, sexism, and nonviolence with accessible language and visuals for elementary school students. Call Me Miss Hamilton can invite students to examine the power of language and naming.

***

Novels

A Ballad of Love and Glory

By Reyna Grande

(Simon and Schuster, 2022)

384 pp.

In an interview about A Ballad of Love and Glory, Reyna Grande says, “How I wish I had known earlier that the state I called home, California, had once been a part of Mexico, and that my native tongue, Spanish, was spoken here long before English. Knowing that might have lessened the trauma of growing up Mexican in a country that made me feel I didn’t belong, that told me in subtle and not-so-subtle ways that I should go back to where I came from.” The fact that California is in the United States and no longer in Mexico is the product of the U.S. invasion of Mexico in 1846, and the war that led Mexico to cede half its territory to the United States — “the war that the U.S. cannot remember and Mexico cannot forget.” Grande’s novel describes that war through a love story between Ximena Salomé Benítez y Catalán, a Mexican woman living near the Rio Bravo (known in the United States as the Rio Grande), and John Riley, an Irishman, who fled the U.S. Army and came to command the Saint Patrick’s Battalion, composed of Irish, German, and other defectors from the U.S. invasion forces. Although this is not a young adult novel, and contains some violence and brief sexual situations, for many high school students it would make an effective introduction to the U.S. war with Mexico. Through Grande’s compelling storytelling, we experience the war from the Mexican side, although not uncritically. She is contemptuous of the “vainglorious caudillos, who allowed their wounded pride to control them.” Ximena is dark-skinned and experiences the racism of the Mexican elite. However, it is the brutality — at times, sadism — of the U.S. military and the Texas Rangers that courses through the novel — but also the humanity and solidarity of Mexicans and their San Patricio allies. Teaching activities about the U.S. war with Mexico can be found at the Zinn Education Project, including a mixer role play on the war and David Rovics’ poignant and student-friendly song “Saint Patrick Battalion.”

***

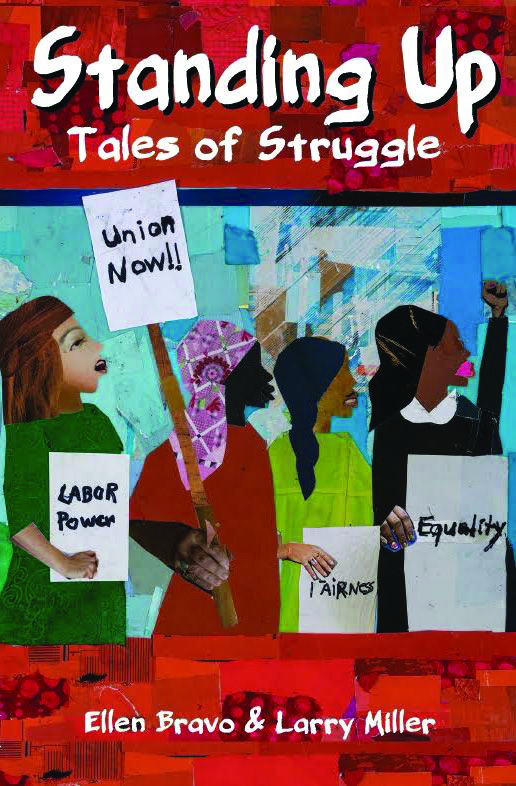

Standing Up: Tales of Struggle

By Ellen Bravo and Larry Miller

(Hardball Press, 2022)

305 pp.

As our students enter the post-high school world of work and/or college, they need stories of how to live lives of love, of laughter, of courage, of struggle for justice — stories that feel real, that feel achievable. Ellen Bravo and Larry Miller have drawn on their many decades together to craft a book that is simultaneously a love story but also an account of how we can bring our values of social justice to life in the workplace. The book offers lyrical snapshots of resistance and solidarity — in hospitals, banks, factories, schools. These stories are told with warmth and humility and offer real-world examples of how we can fight racism, sexism, and homophobia, at the jobsite, but also at home. So often, portraits of radical activism focus on the heroes whose lives are celebrated in biographies, in songs, in films, on posters. But the most useful stories for our students will be those less heroic and more everyday, stories that are road maps for life. That’s what Bravo and Miller offer in Standing Up: Tales of Struggle. These are stories that will inspire and guide — and delight. Full disclosure: Larry Miller is a longtime Rethinking Schools editor; his wife, Ellen Bravo, is co-founder of Family Values @ Work.

***

Poetry

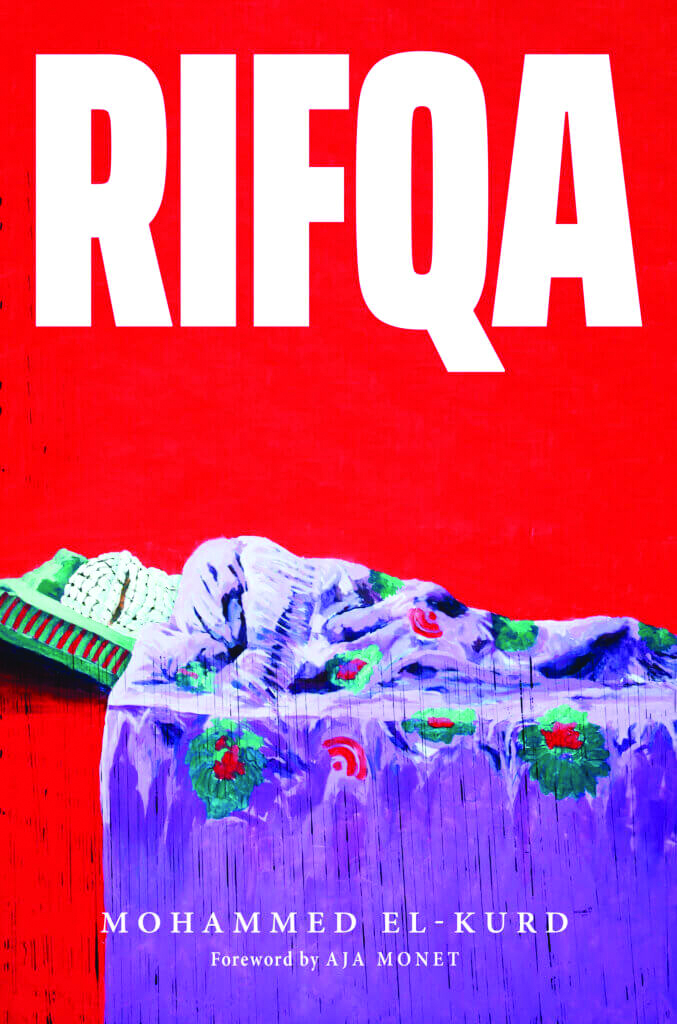

Rifqa

By Mohammed El-Kurd

(Haymarket Books, 2021)

97 pp.

Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear

By Mosab Abu Toha

(City Lights Publishers, 2022)

125 pp.

Two new books of poetry provide windows into Palestinian life. Mohammed El-Kurd is well-known on social media for his on-the-ground reports of Israeli efforts to displace Palestinian residents of his home neighborhood, Sheikh Jarrah, in Jerusalem. In Rifqa, named for his grandmother, he speaks as a poet about the impact of living under constant attack, the resilience of his family and neighbors, and the joy he manages to find in the cracks. “Who Lives in Sheikh Jarrah?” a blackout poem created by erasing words from an article in the New York Times, would work well in classrooms as a model. Many of the later poems in Rifqa were written from Atlanta, and explore connections between U.S. and Israeli racism. (My Neighbourhood, a 2013 documentary about Sheikh Jarrah, stars then 11-year-old Mohammed El-Kurd.)

Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear was written from Gaza. Mosab Abu Toha’s poems are short, accessible, visceral, and beautiful. “Palestine A-Z” cries out for use in the classroom. Each letter of the alphabet subtitles a sentence or two of reflections. For example:

B

Borders are those invented lines drawn with ash on maps and sewn into the ground by bullets.

Y

Yaffa is my daughter’s name. I put my ears near her mouth when she speaks, and I hear Yaffa’s sea, waves lapping against the shore, I look in her eyes, and I see my grandparents’ footsteps still imprinted on the sand.

Students will also be interested in the interview with Abu Toha at the end of the book. He talks about his childhood, what led him to poetry, and the context for some of the poems.

***

Film

All high school students today have grown up in an era when — at least on paper — the U.S. Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision was the law of the land. When Abortion Was Illegal: Untold Stories travels back before Roe, to a time when to get or to perform an abortion was a crime. It is an ugly preview of what awaits us now that Roe v. Wade has been overturned by the Supreme Court. This short documentary points out that until the mid-1800s, abortion was legal and available throughout the United States. The stories in the film — some frightening, some disturbing, some poignant — describe a pre-Roe world of surreptitious, often dangerous, abortions. Students meet some of these women and hear what they experienced in a world when abortion was prohibited by law. “I was 17 years old. I was married. And 10 months after I was married I had a baby girl. She was very ill, very jaundiced, and the doctor told me, the OB-GYN who had delivered her told me that if I ever had another child, I would die. Three months later, I was pregnant again. And I was absolutely terrified. So I went back to him and I said, ‘Am I pregnant?’ And he said, ‘Yes.’ He said, ‘I told you not to get pregnant.’ And I said, ‘But you didn’t tell me how not to.’” Through story, students can recognize the complexity of choices faced by women and question the myths that animate those who seek to appropriate others’ reproductive rights. As one woman in When Abortion Was Illegal says, “A woman that’s unhappily pregnant will risk her life to stop that particular pregnancy. And then, later in her life, when conditions have changed, she will happily risk her life to have a child. This is the same woman.” The film also introduces us to allies — to doctors who risked their careers and their freedom to perform abortions, to individuals who helped women find safe abortions. The film would be stronger with greater racial diversity of its interview subjects, but despite this weakness and being almost 30 years old, this Academy Award-nominated film is a timely and valuable classroom resource. Bullfrog is making it available at reduced rates.

***

Reviewed by Bill Bigelow, Elizabeth Barbian, Jody Sokolower, Deborah Menkart, Linda Christensen, and May Kotsen

Want more content like this? Subscribe now to Rethinking Schools! A one-year subscription is just $24.95 and helps support our efforts to provide antiracist and social justice curriculum and articles for educators everywhere.