“Our Folks Were Badass!”

Learning and Dreaming in Basement

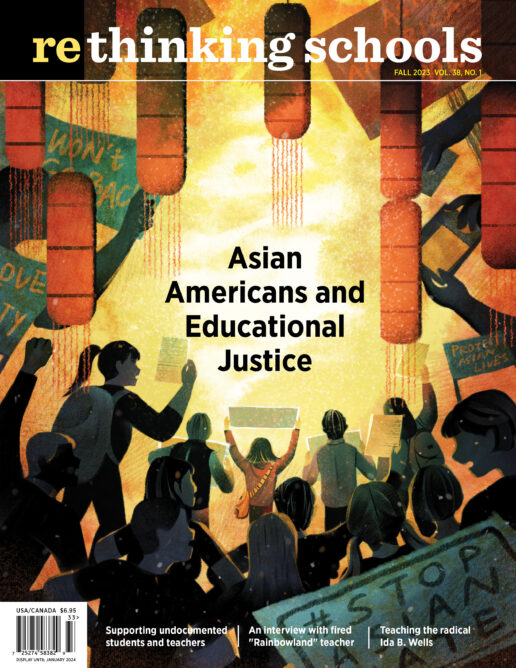

Illustrator: Simone Shin

“See, school never teaches Asian American history!” Adithi, a 7th grader, exclaimed. “Was it because my teacher didn’t know, or she just didn’t care?”

In 2020, four Asian American middle school students, Annie, Adithi, Sunny, and Toni, gathered from their respective basements outside of Atlanta to meet each other virtually after the COVID-19 pandemic hit and their school moved to remote instruction.

Annie self-identified as a Chinese Christian girl, Adithi as a Hindu Indian girl, Toni as a Vietnamese biracial nonbinary, and Sunny as a Korean American girl. The four met in 6th grade and became friends.

To feel connected during virtual schooling and social distancing during the pandemic, the four relied on each other through texting and video chats. Then, one day in 7th grade, they came up with a virtual book club idea to read their favorite books together and talk about their daily lives. They named the book club the Basement because they were literally in the basements of their houses while video chatting.

A Change in the Basement

On March 16, 2021, a white man traveled to three different spa locations in metro Atlanta and killed six Asian immigrant women and two others. This was a turning point for the Basement. The shootings happened only 10 miles from where the Basement crew lived and went to school. They were shocked, scared, sad, mad, and confused. Yet teachers at school said nothing and carried on schooling as if nothing had happened.

This is when I was brought into the Basement. I am the mother of Sunny, one of the Basement members, and the students knew that I was an Asian American studies scholar and social studies teacher educator. So, they asked me to guide them to make sense of the mass killings of Asian immigrant women.

The four decided to turn the Basement into a space for learning Asian American history. They asked me to recommend children’s and young adult literature on Asian American history and regularly invited me to provide historical context on the topics addressed in the books (see sidebar on p. 23). The book club continued until the end of 8th grade, meeting biweekly online or offline. Although specific details were different, the meetings had a general structure. Prior to meeting, students individually read a book and researched the topic related to the book. During the meeting, they discussed the book and the topic and researched additional information using their phones or laptops. Sometimes, they invited me to meetings as a content expert and learning facilitator. Here are some snapshots of the Basement learning.

Asians Have Been in America This Long?

Reading books on early Asian migration such as Coolies and Paper Son, the students were taken aback. “Gosh, Asians have been in America this long?” When I asked, they said that they had learned about the Gold Rush, the transcontinental railroad, and turn of century immigration, which are included in Georgia’s elementary social studies standards, but that no teachers at their schools had mentioned Asian migrants in teaching about these topics. Strong discontent with the curricular omission was palpable. Annie shared that the 4th-grade teachers at her school spent a month teaching Ellis Island and conducted a simulation in which all 4th graders dressed up as European immigrants. Annie remembered: “I was given a role as an Irish girl. It was a fun day running around school. Back then, I didn’t know anything about Angel Island, you know? But looking back now, I am upset. Instead of spending a whole month talking about Ellis Island, teachers could have taught Angel Island too.”

Our Folks Were Badass!

The first reaction of the Basement crew after reading Journey for Justice: The Life of Larry Itliong was disappointment because they remembered learning about Cesar Chavez in 5th grade, the only Latinx historical figure included in Georgia’s elementary social studies standards. “My teacher could have taught Larry Itliong when she taught about Cesar Chavez!” Sunny said. Their second reaction was, however, excitement. “Our folks were badass!” Toni exclaimed. Learning about Itliong’s labor activism and solidarity between the Filipino and Mexican farmworkers was exciting for the students because as Toni said, “I never learned that people like me stood up and fought together with other minorities!”

Everything Happens on Native Land

When they read Coolies, a picture book on Chinese migrants who built the transcontinental railroad, the Basement crew did not notice it was not just Chinese workers, but also Indigenous Peoples, whose stories are excluded in the dominant narrative on the transcontinental railroad. So I probed them with questions like “Whose stories are still missing in this book?” “Whose land was the railroad built on?” They then realized the absence of Indigenous Peoples and conducted internet research to learn about Indigenous experiences with the railroad. Through this process, they wondered: “Did Chinese workers know that they were actually helping the white settlers steal Native lands?” “Were there any sort of Chinese and Native teaming up against white settlers?” The realization “everything happens on Native Land!” and the complicated positionality of Asian immigrants in the United States, a settler colonial state, was a powerful learning moment in Basement. Certainly no book is perfect, and critical reading of books like Coolies is important. What this snapshot shows is that youth-led learning spaces like the Basement may need support from instructors in critical reading of books and inquiring into complex histories.

We Are Here Because You Were There

Books on U.S. wars from Asian American perspectives created rich conversations too. Toni, whose father’s side of the family were Vietnam War refugees, wished their teacher “was honest about what America did to people in Vietnam” so that “kids know Vietnamese people are here because America messed up Vietnam!” Similarly, Sunny noted, “My teacher basically said America went to Korea to rescue poor Koreans from evil communists. I was like, ‘No ma’am! That’s not true!’” Sunny offered to share her family history of the Korean War, but her 5th-grade teacher declined the offer because “we have so much to cover for the Milestone [state testing]!”

We Need to Do Something

The Basement was a special and sacred space for the youth. It was the place where Annie, Adithi, Sunny, and Toni could learn about Asian American history and gain a sense of their own power as Asian Americans.

On Wednesday afternoon, Nov. 3, 2021, the students’ school announced: In celebration of the Atlanta baseball team’s World Series Championship, all schools in Cobb County will be closed on Friday, Nov. 5.

Upon hearing the news, the four began texting:

Annie: No school on Friday!

Sunny: Yay! But sad.

Toni: What do you mean?

Sunny: When the Atlanta mass shooting happened, the school didn’t say anything. Now with the Atlanta Braves winning, all schools are closed to celebrate?!

Adithi: Not surprising.

Toni: They don’t care about us!

Sunny: The game ended last night. Today we got the school closing news?!

Annie: That was quick!

Adithi: Who doesn’t like an extra day off? But the school should not care about only white people.

Toni: What should we do? We need to do something!

Sunny: You guys remember TEAACH Act? Maybe something similar?

Annie: Let’s search up!

The announcement reminded the Basement crew of the school’s silence on the Atlanta spa shootings earlier that year. In stark contrast, when Atlanta won the World Series, the school began the next day with celebration and even decided to have Friday off to celebrate. Frustrated, the four brainstormed what they could do. One action they came up with was to research the Teaching Equitable Asian American Community History (TEAACH) Act, a bill that was passed in Illinois and mandated Asian American studies in the state’s K–12 schools. The Basement crew wanted to know how people in Illinois passed the bill and what it would take for something like the TEAACH Act to happen in Georgia. Through research, they found the legislation was the result of years of hard work involving coalition building and strategic campaigning by various stakeholders. Excited but overwhelmed, the four decided to come back later to talk about what they could do to make similar curricular changes in Georgia.

Basement as a Fugitive Space

Now as they navigate the first year of high school, Toni and Adithi say that they haven’t forgotten their action item. Annie plans to launch a youth book club at her church with focus on Asian American youth literature. Sunny joined Asian American Voices for Education, an Asian American grassroots collective whose mission is to promote K–12 ethnic studies in Georgia. As a student member, Sunny has been creating weekly posts on Asian American history and sharing them on social media. Recently, she got a thank you letter from a teacher in Georgia:

Yesterday, I introduced my class to Bee Nguyen during my Women’s History Month Spotlight and my Vietnamese American students’ faces lit up and the energy in the space was love and everything great! I used some of your weekly posts during my lessons and I plan on introducing them to Patsy Mink this week. I truly appreciate your work and I wanted you to know.

Ideally, school curriculum would be a source of liberation, in which students of all backgrounds can see themselves reflected in school texts, hear from a multiplicity of voices and experiences, learn the truth, and feel inspired to create a better world for all. In reality, systemic erasure of Black, Indigenous, Peoples of Color in school texts contributes to psychological and physical violence against marginalized students. As professors Susan Cridland-Hughes and LaGarrett King write, “While violence on unarmed Black bodies occurs on the streets, the idea of violence against nonwhite bodies begins in the classroom.” This means that when the school texts exclude and misrepresent historically marginalized groups as inferior, unworthy, or dangerous, it sends a message that these peoples are not and should not be valued and cared for. This exclusion and misrepresentation can smother the spirit and humanity of the marginalized students and leave them vulnerable to physical attacks from people who take up oppressive messages.

The stories of Annie, Adithi, Sunny, and Toni show how students of color with community support can form their own fugitive spaces or their own Freedom Schools to learn about their communities’ histories, heal from white supremacy they encounter at school, and dream a radically different future. But, of course, the ultimate goal is that schools themselves transform to be sources of liberation for all students. Above all, the Basement shows how anti-racist, anti-oppressive schools decenter whiteness and center the perspectives, histories, and knowledges of Indigenous communities and communities of color.

Basement Reading List

A Different Pond

by Bao Phi, illustrated by Thi Bui

Vietnamese refugees resettle in the United States.

Coolies

by Yin, illustrated by Chris Soentpiet

Chinese migrants help build the transcontinental railroad.

Dia’s Story Cloth

by Dia Cha

Fleeing the Vietnam War, Hmong migrants escape to the United States.

Finding Junie Kim

by Ellen Oh

A middle school student learns about her grandparents’ experiences during the Korean War.

Fred Korematsu Speaks Up

by Laura Atkins and Stan Yogi, illustrated by Yutaka Houlette

Fred Korematsu struggles for justice during Japanese American incarceration.

From a Whisper to a Rallying Cry

by Paula Yoo

The murder of Vincent Chin galvanizes the Asian American movement.

Front Desk

by Kelly Yang

A Chinese immigrant family’s story centers anti-Black racism, nativism, peer pressure, and learning English.

Half Spoon of Rice: A Survival Story of the Cambodian Genocide

by Icy Smith, illustrated by Sopaul Nhem

A Cambodian child experiences war and genocide.

I Am an American: The Wong Kim Ark Story

by Martha Brockenbrough with Grace Lin

United States v. Wong Kim Ark confirms birthright citizenship.

Inside Out and Back Again

by Thanhha Lai

A Vietnamese girl experiences war and displacement.

Journey for Justice: The Life of Larry Itliong

by Dawn B. Mabalon and Gayle Romasanta

Itliong organizes the Filipino farmworkers movement, in this story of interracial labor activism.

Landed

by Milly Lee, illustrated by Yangsook Choi

A Chinese migrant is detained at Angel Island.

My Name Is Bilal

by Asma Mobin-Uddin, illustrated by Barbara Kiwak

In the wake of 9/11, a boy experiences anti-Muslim hate and discrimination.

Paper Son: The Inspiring Journey of Tyrus Wong, Immigrant and Artist

by Julie Leung, illustrated by Chris Sasaki

A Chinese migrant comes to the United States through Angel Island.

Sixteen Years in Sixty Seconds: The Sammy Lee Story

by Paula Yoo, illustrated by Dom Lee

Olympic champion Sammy Lee was a Korean immigrant in the early 1900s.

Step Up to the Plate, Maria Singh

by Uma Krishnaswami

A Punjabi-Mexican American girl experience during WWII.

Sylvia & Aki

by Winifred Conkling

The book tells the story of an interracial friendship during Japanese American incarceration.

The Best We Could Do

by Thi Bui

A family leaves its home in Vietnam after the war.

Tucky Jo and Little Heart

by Patricia Polacco

A young soldier befriends a Filipino girl during WWII in the Pacific.