Schools, Land, and Peace in Colombia

Illustrator: Barbara Miner

Barbara Miner

Medellín, Colombia—I knew from the invitation that this would not be a normal school visit. My wife, Barbara, and I were to travel into the Andes Mountains to visit an Indigenous school that is at the crossroads of Colombia’s future. The school, Institución Educativa Natalá, is a stronghold of the Nasa people’s attempt to protect their language, their culture, and their land. The Nasa, in turn, are among roughly 100 Indigenous tribes in Colombia, where the struggle to protect Indigenous lands is a fundamental issue in the country’s emerging peace agreement.

I’ve been a bilingual teacher and union activist in the United States for more than three decades. When Barbara and I went to Colombia in September for several months to improve our Spanish and to meet with education activists, we arrived at a historic time. Following an initial peace accord in Havana last September, the Colombian government and the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) set a March 2016 deadline for a final agreement.

Throughout Colombia, from the cosmopolitan cities of Bogotá and Medellín to the smallest hamlets, people are cautiously hopeful that the peace accords will end Latin America’s longest guerrilla war, one that has stretched over half a century. But Colombia has long been a country where vast rural areas are under the control of extra-governmental forces, whether right-wing paramilitaries, mining companies, drug traffickers, or leftist guerrillas. These rural areas have the most to lose if the accords are poorly implemented and lead to a power vacuum that might allow armed gangs to dominate areas, enabling even more exploitation of Colombia’s resources and even more displacement of campesinos and Indigenous peoples.

Plinio Ñuscue, a member of the Indigenous Guard of Cauca that accompanied us on our school visit, explained that land has always been at the core of Colombia’s power struggles: “Our ancestors lived on the plains when the [Spanish] colonizers came. They wanted our land and forced our ancestors off the land and into the mountains. Now, when they have discovered these mountains are rich with minerals, they want to take these lands as well. We will not move.”

We had been invited to the school by a member of the Nasa tribe who attends the University of Santiago in Cali, where I have several friends among the faculty. Along with two friends from the university, we met the Indigenous Guards in a small town about two hours from Cali, Colombia’s third largest city. The Indigenous Guard of Cauca was formed years ago to protect the Nasa people and their lands. They are armed with the respect of the community and with wooden batons adorned with ribbons of red and green signifying sangre y tierra—blood and land.

The guards escorted us out of town—one motorcycled ahead of our car, one behind. We were careful not to lose sight of them. A wrong turn on the mountain roads could mean hours of being lost. The guards also provided protection. Despite Colombia’s much-improved safety since the days of the Medellín and Cali drug cartels, security remains a concern. We knew that Toribío, where the Nasa school is located, has been the site of contentious struggles in recent years to defend tribal sovereignty.

The asphalt road soon turned to gravel as we made our way up the mountain on hairpin curves. At times, the road was nearly blocked by landslides or road washouts; other times, it was temporarily blocked by a wandering bull or a horse-drawn cart. Dogs, roosters, and chickens scattered as we drove past fincas where campesinos tended small plots of coffee and sugar cane.

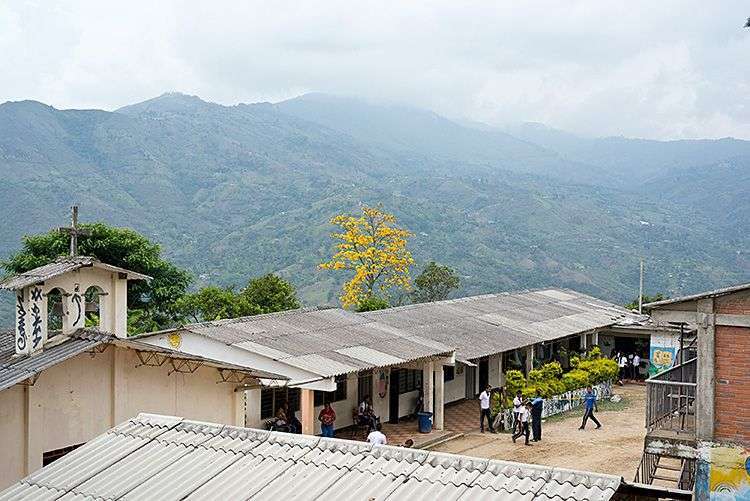

After 45 minutes we arrived at the school, deep in the Andes. We soon learned why motorcycles, horses, and traveling by foot are the most reliable forms of transport in the mountains. Our car valiantly tried, and failed, to make the final leg of the journey. We walked.

At the school, we were met by another member of the Indigenous Guard, who unlocked the iron gate surrounding the school. This campus holds grades 6 through 11; the primary school is farther up the mountains. Together, there are about 430 students.

Inside, the campus was a scene of calm and order, albeit infused with youthful energy. Students greeted us, smiling at our U.S. accents as we conversed in Spanish. We were ushered into the cafeteria and, over hot milo (a malted chocolate drink) and bread, began our conversations with school leaders. They proudly showed us the tile mural on the cafeteria’s back wall, which pictures the local priest and Nasa leader Father Álvaro Ulcué Chocué. The first Indigenous Catholic priest in Colombia, Father Álvaro was assassinated in 1984 by military forces.

A quick tour of the school included everything from small, sparsely lit classrooms with brick walls and simple wooden chairs, to an organic garden, to a modern kitchen classroom where students and teachers create juices, breads, and other foods with the local produce for student meals and to sell to the community.

I had assumed we’d visit classrooms and observe a normal school day. But our hosts had other plans. We were ushered into the empty meeting hall and told to sit at the lone table in front. Within minutes students filled the hall, carrying their own plastic chairs and setting them in rows, ready for an all-school assembly.

A group of students played Indigenous music, then school leaders welcomed everyone bilingually—in Nasa Yuwe and in Spanish. It was clear that the school was a source of deep pride. The comments by the principal and the Indigenous Guards, in particular, stressed the need to respect and protect the Nasa culture and to use education to benefit the entire community. Our hosts hoped that having a group of visitors from the prestigious Universidad Santiago de Cali and from the United States would remind the students of the school’s importance.

Then we met with the teachers and the principal in a classroom while the students were left on their own. As we talked with the teachers, I was struck by similarities with issues faced by language minorities in the United States. As a bilingual teacher and education activist, I have long been aware of the importance of language in protecting culture and the rights of language minorities. The pull of the dominant language and culture is always strong. Instilling a sense of history and culture in students, especially in an era of iPhones, can be difficult.

The staff talked about the challenges in building a quality bilingual school. Lack of funding was clearly a problem, whether to pay for computers or books or to improve the buildings. Some teachers blamed neoliberalism—the term used throughout Latin America to refer to free-market policies—not only for the lack of funds, but also for the general decline in Indigenous culture and language, and for the growing power of privatization and consumerism. They see neoliberalism in total opposition to a tribal sense of community.

“We need to rescue our Nasa Yuwe language [from extinction],” one teacher told me. “Most parents support our attempt, but the focus can’t be just our school. It has to be the families.” The teachers have formed an escuela de padres—school for parents. “We meet with the parents every few weeks to talk about what’s going on in the school and to emphasize the importance of them talking every day to their children in Nasa Yuwe,” the teacher added.

The teachers expressed a strong belief in the bond between school and community, and how both must work together. My mind was filled with memories of meetings in the United States where we talked of similar issues and also developed strategies to involve parents and community.

One of the key issues facing the Nasa people is the threat of being thrown off their land. Displacement is a key issue throughout Colombia. Due to decades of upheaval, Colombia has an estimated 5.7 million people who have been internally displaced. It is the second highest rate of internal displacement in the world, after Syria, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Indigenous people and Afro-Colombians are disproportionately represented among the displaced in Colombia.

As land has been cleared of its original inhabitants, Canadian, U.S., and European multinational corporations—oil companies, mining companies (coal, gold, and emeralds) and agribusiness (sugarcane, palm oil)Ñhave moved in and expanded operations.

Too often, these incursions have been enabled by U.S. support of the ruling Colombian oligarchy. More than $7 billion dollars in U.S. military aid flowed into Colombia from the 1990s through the mid-2000s to fight narco-traffickers and leftist insurgencies. The Colombian government simultaneously used military and private paramilitary groups to attack and murder thousands of labor, Indigenous, Afro-Colombian, and human rights leaders throughout the country. As the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Center for International Studies noted in 2008, Plan Colombia is “a counternarcotics strategy that has turned into a counterinsurgency one.”

A few days after our visit to the Nasa school, a teacher union activist who had been active against right-wing paramilitaries was assassinated in the north of Colombia. Overall, assassinations and disappearances, especially in smaller cities and rural areas, remain disturbingly common in Colombia. Leftist guerrillas are not without blame, but there is near unanimous agreement that right-wing paramilitaries account for the majority of the crimes.

At the Nasa school, and throughout Colombia, people clearly support the peace accords; there is a deep yearning for peace and for the chance to rebuild the country. As we went to press, the peace talks were still under way; the March 23 deadline passed without a final agreement, but the intention of both the FARC and the government is to have an agreement soon, followed by a referendum in October.

Unfortunately, even the anxiously awaited peace accords hold risks. A recent gathering of more than 37,000 participants at the conference of the Latin American Council of Social Sciences in Medellín issued a strong statement favoring the peace process. Boaventura de Sousa Santos, a Brazilian scholar who founded the World Social Forum, reminded the group: “A territory free of conflict is free for great resource and industrial exploitation.”

The Nasa people are living this contradiction. They, too, want peace. But they also know that Colombia’s future is inextricably tied to the future of Indigenous lands, schools, and culture.