On Behalf of Their Name

Using They/Them Pronouns Because They Need Us To

Illustrator: Alaura Borealis

“When someone with the authority of a teacher describes the world and you are not in it, there is a moment of psychic disequilibrium, as if you looked into a mirror and saw nothing.”

—Adrienne Rich

Adrienne Rich’s quote illuminated the projector screen welcoming teachers as they entered the library for a 90-minute training on gender and sexuality acceptance led by the Queer-Straight Alliance (QSA) — a student organization that I am the staff advisor for. Our large urban school holds about 100 staff members. Maybe 3 percent looked forward to this training. The rest sat with their arms crossed, present only because admin mandated their attendance.

The QSA youth pushed for this training all year. At last, late February, here we were. In my final year of probationary teaching, I stood mere weeks away from receiving my permanent contract. Job security slinked at the brink of my reach. And I feared ruining it all.

I felt panic at the thought of losing my job for being a transgender and queer teacher leading transgender and queer students. This “liberal” community and its wealthy, demanding parents held power and sway that made my nerves pulse irregularly. I woke some nights in a sweat from nightmares of tantrum-throwing parents and their hate-inspired monologues directed at me: “What even are you?! Despicable! Unfit to be around kids — how dare you. Stay away from my kid!” When you are a member of a marginalized group — especially one that’s been villainized and degraded — safety is not an automatic privilege, even when you’re white. Although my whiteness does provide shelter that trans and queer teachers of color are not afforded.

The students and I met to plan the staff training for several weeks before the February meeting. Youth were both gung-ho and noncommittal. The students really wanted to yell at the staff, misgender, and ridicule them. These students hurt and wanted to lash out to ease some of their pain. Many of them felt strongly, but few of them wanted to stay after school for two hours and say anything into the sea of mostly heterosexual, entirely cisgender teachers. They were great balls of fury and they wanted to pitch fire in every direction at once. Few had the energy necessary to face the staff in a meeting.

These teachers were supposed to be theirs. Students say, “My teacher.” This simple possessive pronoun makes the pain of not being seen by that same teacher feel like a self-inflicted wound. Some teachers ridiculed students in front of the class, scoffing at the idea or trouble of using they/them pronouns. One teacher told our VP: “Well, what is the kid biologically? That’s what they are to me.” The incredulousness of this statement essentially translates to: “What’s that kid’s genitalia — students are equivalent to their genitalia.” No teacher needs to be thinking about children’s genitalia.

During the weeks of planning for this training, I floundered in a borderland where I wanted/needed to be with the youth — really have their backs and support their lived experiences, listen to them, validate them. But also being an adult and a colleague, I worried that yelling at staff wouldn’t change anything. And we really needed staffwide change. Students skipped classes, students hurt — each other and themselves — students avoided their education because adults couldn’t just get their names right. Everything begins with a name. We exist because we know each other by name. Youth change their names because this gives them the power to exist. To refuse to call a student by their painstakingly chosen name — whether it matches the gradebook or not — denies a student’s right to be wholly present. This erasure snatches away identity just barely emerging.

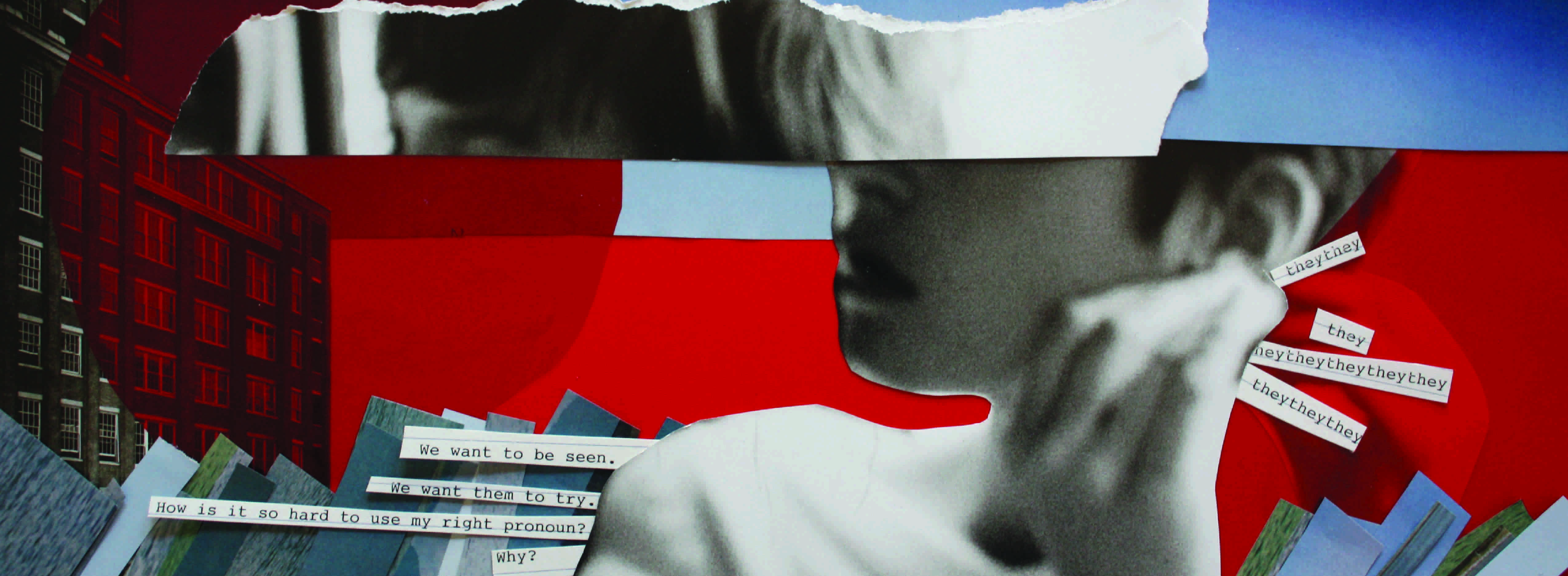

I kept asking the QSA these questions: “What outcome do you want? What is your purpose in this training? Do you want to educate the teachers? Share your stories so they’re known?” Aliya said, “We want to be seen. We want them to try.” Sal added, “How is it so hard to use my right pronoun? Why?”

While politicians and professionals and teachers argue about the morality of gender variance, real children are disappearing in the classroom — figuratively and literally. Two trans students dropped out by second semester, another was on the verge, QSA members barely hung on, and our school later lost a transgender student to suicide. And this in a very liberal district at a high school with gender neutral bathrooms.

I let them hash out their ideas for a couple meetings without much of my own input. I would nod and say yes and affirm. I’d empathize and I meant it all, but inside I was kind of freaking out. Will this implode? Is staff just going to scoff and roll their eyes? Will they even listen or just be on their phones the whole time? What if students don’t show? What if my colleagues blame and hate me for all this? What if I get fired? Am I really going to come out to my whole staff in this training?

Yes, I am.

As soon as the staff settles into their seats we start off with a video of Olive, the vice president of the QSA. Olive nods at me with tightened lips, and I hit play: “My name is Olive Reed and I use they/them pronouns.” The video follows Olive moving through their day and discussing their experiences with school being safer than home but that they are called a faggot nearly every day. Olive says, “Everything in our society is binary, it’s not just gender. But when you don’t fit into that binary, take a step back and you’re like, but what about me? And it’s just — it feels like — there’s not a place for me in this society.” Teachers are watching, rapt with attention. Olive believes that “no one should have to hide who they are because of fear. No one should have to be afraid of being able to be who they are.” When I first saw this video, I knew I couldn’t support the students in this training and not come out to my colleagues. I owed them the overcoming of my own fear, I owed them my vulnerability. Olive’s video ends with a quiet call to action: “People are accepting enough that you can come out, that you can openly be who you are, but people are not accepting enough for everyone to be safe. Yeah, we’ve made a hell of a lot of progress, but no, we’re not anywhere near resolving anything.”

At the video’s end I instruct staff to write down striking thoughts and questions before sharing out at their tables. Many of the responses reveal appreciation for Olive’s bravery and vulnerability. To not overcook Olive’s anxiety about being the center of attention we move on to our intros. Three (of several) students and I give our names and pronouns:

“My name is D’Angel, I use he/him pronouns.”

“My name is Olive, I use they/them pronouns.”

“My name is Asuna, I use she/her pronouns.”

My heart pounding against my vocal cords, I finish us off: “My name is Mykhiel Deych, I use they/them pronouns.” Shuffle, shuffle. Swallow.

A pulse of invisible energy ripples through the four of us and out over the crowd. Air shimmering like the waving heat over an open grill in summer. D’Angel says with a smile, “Now please go around at your tables and say your names and pronouns.” Some eyes roll and lips snarl, yet most of the staff conform to the simple task. A QSA member is seated at nearly every group table to help with intros. I mean, it is simple, isn’t it? Just state your name and pronoun. Not far from the common instruction to state your name and birthdate or name and subject you teach. The norm of introductions at the start of a meeting feels familiar. Why the resistance to pronouns then?

The prefix “pro” means on behalf of. In English, we have gendered pronouns, so to use a pronoun in place of a person’s name imbues onto the person a slew of gendered meaning that acts to define and/or limit the identity of that person. Students struggle to come into their identities no matter what. Becoming a self challenges everyone. One’s gender should be a given, right? The easy part, the part of identity you’ve had since you were a kid, right?

Along with a handout, the next video, Sex & Gender Identity: An Intro, briefly defines and explains key terms: Sex is the biological classification of being female or male or intersex and is assigned at birth. Gender Identity is one’s deeply held sense about gender and is not the same as sex. Gender Expression is the external manifestations of gender expressed through a variety of ways including but not limited to clothes, hair, name, pronoun, voice, behavior, etc. Transgender is an umbrella term for people whose gender identity and gender expression differs from their sex. Cisgender is a term for people whose sex at birth matches their gender identity and gender expression. Genderqueer is a term for people who do not identify as part of the female/male binary and may experience themselves as both or neither. Genderfluid is a term for a gender identity that varies over time. And lastly, the verb that brought us into the room: Misgender. To misgender someone is to identify a person with a gender that they aren’t. For example, when you call me a lady or ma’am you have misgendered me.

Teachers start sharing out about any newfound understandings or questions on the video. One teacher shares a painful incident. Mr. Xon says, “I don’t know about these things but what I know is that I let a student go to the bathroom and they take a very long time and when they return I ask them where they’ve been and the student says, ‘I had to go to the gender neutral bathroom.’ OK, but I don’t know if that’s really what’s happened or not.” He stays standing for a moment palms open, facing up. He is trying to understand.

The room hushes; I take a slow breath, and another. But before I say anything, Asuna steps forward to respond, “The only gender neutral bathroom is far from your classroom, and there is almost always a line for it. This is really hard for us. We need you to believe us.” This raw bravery and unapologetic vulnerability inspires me and I shiver. Are teachers that most need to hear this absorbing anything? All the students’ hard work — is this going to change anything?

To provide a few tangible tools we put up a slide that has problematic phrasing replaced with simple solutions. Sally reads off, “Instead of calling the class to attention with ‘ladies and gentlemen’ try ‘scholars’ or ‘mathematicians.’ Instead of dividing by ‘boys and girls’ use ‘favorite foods’ or ‘wearing blue,’ etc. Avoid blanket statements like ‘all boys this’ or ‘all girls that.'”

A teacher shares out apologetically, “I don’t use the they/them pronouns because I just know I’ll mess it up.” Griffin replies, “Messing up isn’t the problem, we know it’s hard to get used to, we actually just want you to try.” They don’t say it with a smile, but it comes out calm. An audible and affirmative “hmm” sounds out at a few of the tables. After sitting for a long time we shake things up.

Kaitlin instructs into the mic: “Please stand up and if you are a dog person stand over here and if you are a cat person please stand over there. She points to the far ends of the room and a gap in the middle widens as teachers move to where they belong. A few students and teachers vacillate between the two sides and end up in the middle with furrowed brows and heads tipped to one side. One teacher raises her hand and says, “Well, I don’t like either.” Another says, “I used to like dogs but now I’m more about cats, where should I go?” And another asks with a deep shrug, “But I like both. Where do I belong?”

Where do I belong? The question hangs in the air as several teachers release audible gasps as they catch on to the metaphor they’ve just played out. “Wait, I get it, students maybe feel like this about their gender. Or sexuality too, right?” Ms. Smith says and taps a finger to her lips. Some eyebrows furrow. Some grins appear. Nods slowly bob through the clumps of solidly “dog people” and solidly “cat people.” If only gender was a simple choice.

Teachers chat it out as they return to their seats to try role plays where they practice four important interactions: asking for someone’s pronouns, using they/them pronouns in a conversation, correcting someone misgendering someone else, and correcting themselves misgendering someone. I circulate around the tables. At least one student sits amongst each of the table groups. The role plays open a flurry of activity at each table. The air full of electricity, my breathing feels steady until suddenly, one table gets superheated. I rush over to intervene and arrive in time to hear Kaitlin nearly shout, “It is grammatically correct, we already use they/them pronouns when referring to one person when we don’t know a person’s gender.” I lock eyes with Kaitlin and she grins, “I got this M. Deych. Thanks, though.” She is proud of herself. Proud to debate a teacher we already knew going into this training would be a wall to take down brick by brick.

When we come back together as a whole group, another teacher asks, “Are we really expected to keep track of when it is and isn’t OK to use a student’s preferred name or pronoun?” After so much of the training going well, the hostility in this question stuns me speechless. My head races. You know how we have all that training about getting to know students, building relationships?! Well, this is that! To my appreciative surprise, another teacher responds, “Well, we’re not talking about a huge percentage of your class here. This comes down to a few students on your whole roster probably.” Thank you, allies, I need your help — students need you.

The training finishes with a panel that responds to teachers’ anonymous questions written on scraps of paper that were at each table throughout the whole training. Three students, a parent of a transgender student, and I sit on the panel. Unfortunately, the final question deflates a lot of the gains we’d made: “I just can’t use they/them pronouns, it’s wrong, and I just can’t. What do I do?” I probably don’t hide the irritation when I reply, “No one is expecting the grammar to change. It isn’t wrong. You use it grammatically, not ‘they is home sick’ but ‘they are home sick.’ And if it helps to know, the reason many of us — the reason I — use they/them pronouns is because it reflects the multiplicity that I experience in my gender. So it is actually very right.” Griffin relays their story of battling depression and ends with their head held high, “We actually just need you to try.”

The students left feeling hurt by this last statement/question. It haunted them. And though issues persist with certain teachers, overall progress accumulates. Multiple teachers thanked me for supporting the students in that training. One said she felt defensive at first but then it really was good to hear about the students’ experiences. Another came to me to hash out and discuss the issue with “ladies and gentlemen.”

It’s ongoing, the work of showing up for students how they need us to show up. With 41 percent of transgender people attempting suicide (compared to 1.6 percent of the general population), we have to because they actually need us to.