Of Mickey Mouse and Monopolies

A new book explains how the media came to be dominated by a few mega-corporations – and what this means for democracy.

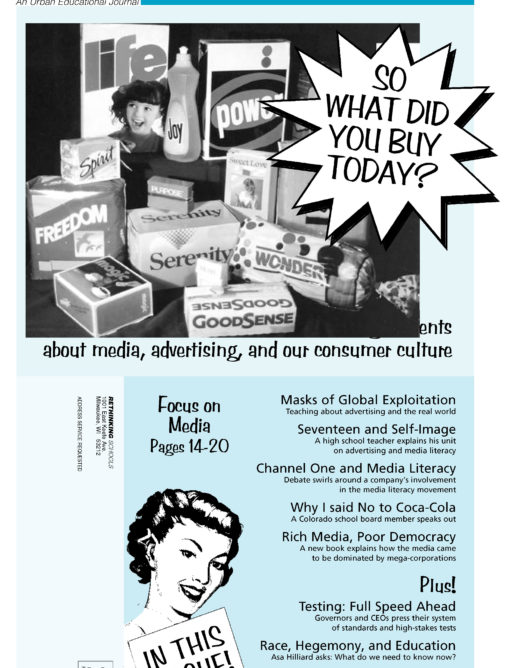

Rich Media, Poor Democracy

By Robert W. McChesney

University of Illinois Press, 1999

Robert McChesney’s Rich Media, Poor Democracy is a scary book. If one of the corporate media giants that McChesney examines ever bought the movie rights (a non-existent possibility to be sure), it could make a latter day version of those ’50s monster films: maybe “The Thing That Devoured Our Culture.” Unfortunately, the book is not fiction.

McChesney is a professor at the University of Illinois and a prominent progressive media critic. His latest book combines political economy, history, and civic concern to analyze the emergence of a global corporate media system that reflects, and helps to shape, a world where democracy is in serious trouble. His main theme is “the contradiction between a for-profit, highly concentrated, advertising-saturated, corporate media system and the communication requirements of a democratic society.”

McChesney’s book is valuable to educators on several counts. It catalogs the astounding growth of the transnational corporations that increasingly dominate all forms of media, from radio and TV to movies, music, and book publishing, from newspapers and magazines to the Internet and telephone networks. If we are going to add “media literacy” to the curriculum, this information should be part of it.

It also shows how this system, which has “marinated” our society in commercialism and the pursuit of private profit over common good, was not a “natural evolution,” but was socially constructed. McChesney recounts the history of corporate power plays, government regulatory abuse and the suppression of public debate that created the media system we have today. [Along the way, he retells a little-known chapter in this history in which educators made a last stand on behalf of public rather than private control of media. See sidebar]

Finally, McChesney’s work is animated by an activist commitment to media reform and democratic social change. Efforts to promote “media literacy” would be strengthened by considering his calls for structural reform and alternative media systems.

CONCENTRATION AND CONGLOMERATION

Even readers aware of the trend toward corporate concentration will be struck by the consolidation of media power over the last decade. In 1983 Ben Bagdikian’s The Media Monopoly found the media market dominated by about 50 large firms. As McChesney notes, Bagdikian’s 1997 update identified just 10 firms with comparable power. Media sectors that were once relatively open and competitive have, with government help, dramatically consolidated. In 1985, 12 firms controlled 25% of all movie theaters, by 1998 they controlled 61%. Some 80% of book retailing is now controlled by a few national chains, as the share of sales by independent book dealers fell from 42% to 20% in the mid-’90s. Today six firms control 80% of the nation’s cable TV hook ups. Even “alternative weekly newspapers,” once seen as local outlets of independent thought, are now dominated by a few national chains.

Along with concentrated ownership has come conglomeration, the “process whereby media firms began to have major holdings in two or more distinct sectors.” Disney, Sony, Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp., Time-Warner, Viacom, and Seagram are the “first tier” of media conglomerates. These media empires now stretch across every aspect of media production and distribution.

For example in 1988, Disney was a $2.9 billion “amusement park and cartoon company.” In the ’90s it grew nearly 10 times as large, and now owns the ABC TV and radio networks, part or all of over 10 cable stations (including ESPN, A&E, and Lifetime) and three major film studios. It has major holdings in book publishing, the travel and resort business, music recording, and 660 retail outlets. It also owns two professional sports teams, plus TV production and Internet companies. Numerous other assets today make Disney a $25 billion company.

McChesney traces these trends internationally and finds a global media system that is “fundamentally noncompetitive,” dominated by about 10 transnational corporations. The system plays a central role in the development of what he calls “‘neoliberal’ democracy; that is a political system based on the formal right to vote, but in which political and economic power is resolutely maintained in the hands of the wealthy few.”

The “hallmark” of this global system “is its relentless, ubiquitous commercialism.” U.S.-style TV shopping networks now span the globe. Disney and McDonald’s have a 10-year agreement to promote each other’s products in 109 countries. Music, sports, and children’s programming strategies are increasingly global, with Viacom’s Nickelodeon thriving in Latin America and Time-Warner’s Looney Tunes now a $4 billion, multilingual, worldwide money machine.

Two trends, “hypercommercialization” and “synergy” describe how media conglomerates squeeze maximum profit out of their corporate bulk. Hypercommercialization refers to the ceaseless effort to increase the reach of all forms of advertising. Synergy refers to the use of overlapping corporate partnerships to maximize product tie-ins, distribution, and marketing schemes.

Some examples:

- The number of TV commercials packed into the same time slots is way up. Disney’s ABC leads the way, having increased commercial time 34% over the past decade.

- One half of the 27,000 U.S. movie screens now show ads before films.

- Wal-Mart shows ads on TV monitors to customers waiting in register lines, while Disney and Gillette created ads to place on the sticks that separate individual orders at checkout counters.

- A recent Jim Carrey movie, Liar, Liar, was promoted with tiny stickers placed on 12 million apples.

- Outdoor advertising was up 80% to $4.5 billion by 1997. The latest innovation is “street furniture”: bus shelters, newsstands, even public benches and buses wrapped in brightly-colored vinyl advertisements. New York City recently signed a $1 billion “street furniture” deal to increase commercial pollution of city streets. Floors in public buildings, cash machines, even bathroom stalls are now all fair game.

Synergy reinforces this hypercommercialization as the different arms of media megafirms work hand-in-hand to maximize profits:

- Some publishers now check with book chains to see if they’ll carry a book before they contract with an author to write it.

- There’s been a virtual return of the “payola” scandals of the ’50s, whereby radio stations promote the musical products of their sister divisions. Similarly Viacom’s MTV runs movie preview specials only for studios that advertise heavily on the network (and who pay production costs for the shows).

- The media/advertising domination of sports has resulted in 28 U.S. major league franchises being controlled by media companies, with tie-ins to cable programming, product merchandising, even the launching of new leagues and new sports (i.e. ESPN’s “extreme sports”).

These trends have fed what McChesney calls the “rampant commercialization of U.S. childhood.” Media firms work to develop brand recognition and product loyalty from birth. The strategy is to create a recognizable identity through advertising and then clone it through endless product tie-ins and spinoffs. Disney’s animated films now make four times more on merchandising than on domestic box-office. The Lion King alone generated 186 items. Murdoch’s Harper Collins publishing company has developed 90 products carrying the Little House on the Prairie logo, from paper dolls to cookbooks. The current Pokemon craze is just the latest example, “the result,” according to The New York Times, “of a calculated series of creative and marketing decisions aimed at learning the lessons of previous toy fads.”

The aim is to have children influence family purchases. “The parent doesn’t want to get anything the kid is going to complain about,” says one marketing consultant. “It’s not efficient.” In addition, children, (at least those not among the 20% of U.S. children who live in poverty) are a market in their own right. In 1997, kids ages four to 12 spent $24 billion. By age seven, the average child is watching 1,400 hours of TV with 20,000 commercials a year.

Inevitably, this commercial assault reaches into schools. Firms are paying to have ads in textbooks. “Fast food snack and soft drink firms have launched a successful attack on school cafeterias.” Pepsi and Coke battle for exclusive rights to install soda machines and scoreboards at local high schools. This commercial warfare reached absurd levels at a Georgia high school in 1998 where a student was suspended for wearing a Pepsi shirt on a day everyone was supposed to wear Coke shirts as part of a school-endorsed promotion.

The commercial penetration of schools includes the Channel One network, and, as McChesney notes, further market reforms like vouchers “would almost certainly enhance commercialization at public schools, as their need for money would increase as their students take their vouchers to private schools.”

One of the strengths of McChesney’s book is its ability to cut through the mythology of the marketplace. McChesney shows how markets can lead to noncompetitive, monopolistic practices that narrow choice and reproduce inequality. “In sum,” he writes, “the mythology of the free market serves to protect the interests of the wealthy few, those who benefit from having the market rule near and far without popular ‘interference.'”

McChesney also shows how the bottom-line logic of commercial markets can have corrosive effects on media content and on activities vital to the health of a democratic society, including journalism, public participation in civic life and political campaigns. “A commercial marketplace of ideas may generate the maximum returns for investors, but that does not mean it will generate the highest caliber of political exchange for citizens. In fact, contemporary evidence shows it does nothing of the kind.”

Blind faith in the power of the marketplace has not always been the rule, however, as the book’s section on the history of broadcast regulation and policy makes clear. It should be required reading for anyone wondering how we got into this mess.

PUBLIC INTERESTS UNDERMINED

As each form of media technology developed, efforts to assert public interests over market and profit considerations have been undermined or defeated. In a typical pattern, private interests establish their claim to and increasing control of an emerging technology (e.g., radio, TV, the Internet). Government regulatory agencies aid and abet this process, combining rhetorical lip service to public service obligations with toothless enforcement. Momentous policy decisions are made with minimal debate and virtually no acknowledgment that the public even has a right to discuss who should own and control the media networks which play a growing role in political, social, and cultural life. Eventually the corporate-dominated, commercial system is presented as the natural order of things.

The latest phase of this process involves the Internet (itself the product of public government subsidy to academic and military researchers). McChesney notes that the decentralized, interactive Internet does not readily fit other “regulatory models.” But he also sees through illusions about how the Internet will “revolutionize” society by combining “a belief in technological magic with a faith in the magical markets.” Instead McChesney shows how in the mid ’90s, Internet technology mixed with familiar patterns of government-supported corporate power to create a medium wholly amenable to commercial corporate control.

The development of the World Wide Web, the Internet’s graphic, “user-friendly” face, facilitated this commercialization, but the keys were government policy decisions, again made in relative secrecy with little debate. One was the decision to privatize the “Internet backbone,” the network of fiber-optic trunk lines that form the “in- formation superhighway.” The Clinton Administration (including self-proclaimed Internet “pioneer” Al Gore) gave control over the Internet’s infrastructure and technological protocols to a handful of telecommunications giants like AT&T and MCI at no cost. A second step was passage of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, the first major piece of federal legislation in the area since the Communications Act of 1934 privatized the airwaves.

At the time, considerable public attention was given to the Communications Decency Act, a companion piece of legislation that was later declared unconstitutional for its attempts to censor Internet content. But the Telecommunications Act itself passed with little notice. Its primary provision was a scandalous giveaway, estimated at anywhere between $40-$100 billion, of the digital communications spectrum to the existing broadcasters. This assured that digital technology, which promises to merge TV, Internet, telephone and other communications services over the next decade, will remain in familiar corporate hands. As McChesney writes, “The ultimate importance of the corrupt Telecommunications Act of 1996 was and is to establish that the private sector would determine the future of U.S. and electronic digital communication.”

“Corporate dominance and commercialization of the Internet,” he continues, “has become the undebated, undebatable, and thoroughly internalized truth of our cyber-times. It is a clear reflection of the strength of corporate power in the U.S., and of the weakness of democratic and progressive forces.”

Strengthening those “democratic and progressive forces” is a prerequisite for effective media reform, not only of the Internet, but on all fronts. McChesney ends his book with an extended argument for making structural media reform a central part of a broad progressive agenda for democratic social change. Specifically he calls for:

- Building nonprofit and noncommercial media with financial support from foundations and labor.

- Strengthening public broadcasting, and adding new local and public access components.

- Effective regulatory action, including charging commercial broadcasters for their use of the public spectrum and using those license fees to fund alternative media. He also proposes limiting commercial licenses to 18 or 20 hours a day to free up space for noncommercial programming.

- New anti-trust efforts, including a new media anti-trust statute to weaken the grip of the media conglomerates and combat monopolistic practices.

“The key,” McChesney concludes, “is to present media reform as part of a broader package of democratic reforms addressing electoral systems, taxation, employment, education, health care, civil rights and the environment … as part of a broad left agenda.”

Rich Media, Poor Democracy makes a powerful case about what’s wrong with the current media system and what could be right with a very different one. It ultimately calls for a new kind of “communications revolution” that may be televised, but only if it’s won.