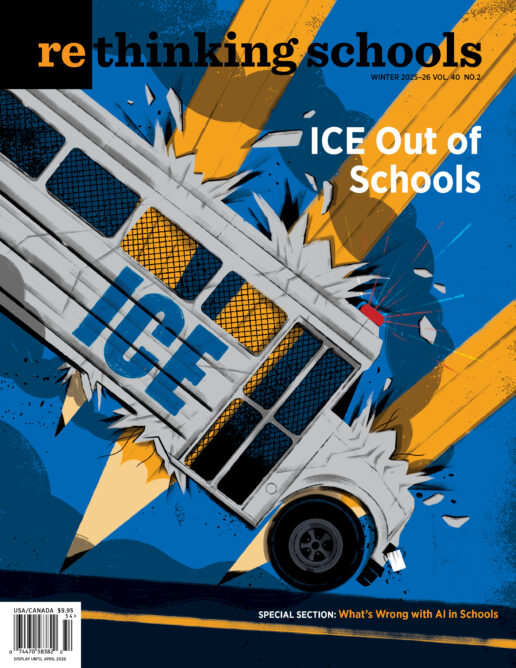

Now Is the Time to Defend Our Students

LA Educators vs. ICE

We didn’t plan to spend our summer break looking for ICE.

We had thought about taking a road trip to Montana. When those plans fell through, we figured we’d have a relaxing couple of months at home in San Pedro — Los Angeles’ southernmost neighborhood, where the rocky coastline meets the sprawling Port of Los Angeles and Long Beach. As classroom teachers with two young children, summer break is sacred — a time to recharge from the unrelenting grind of the school year, catch up on reading, and see family. After a difficult year of school and union work, we were looking forward to a summer of beach days and picnics in the park.

But the federal government had other plans. Immigration raids began in full tilt the first week of June. Photos and videos of sightings were flying across social media and protests were erupting downtown. Attendance dropped in our classrooms. Shock and confusion turned to fear and anger as we learned that the National Guard was being deployed to suppress battles raging in the streets.

Things turned personal on June 10 — the last day of school — when we got a call from our daughter’s daycare, letting us know that immigration agents were on their way and that staff was going into lockdown. We quickly called friends and neighbors who assembled outside of the daycare within minutes, armed with protest signs and know-your-rights material.

No immigration enforcement agents arrived, and the information the daycare had received turned out to be a false alarm, but the response we’d witnessed from friends and community members was powerful, and it convinced us that our neighborhood was ready to organize against Trump’s immigration crackdown.

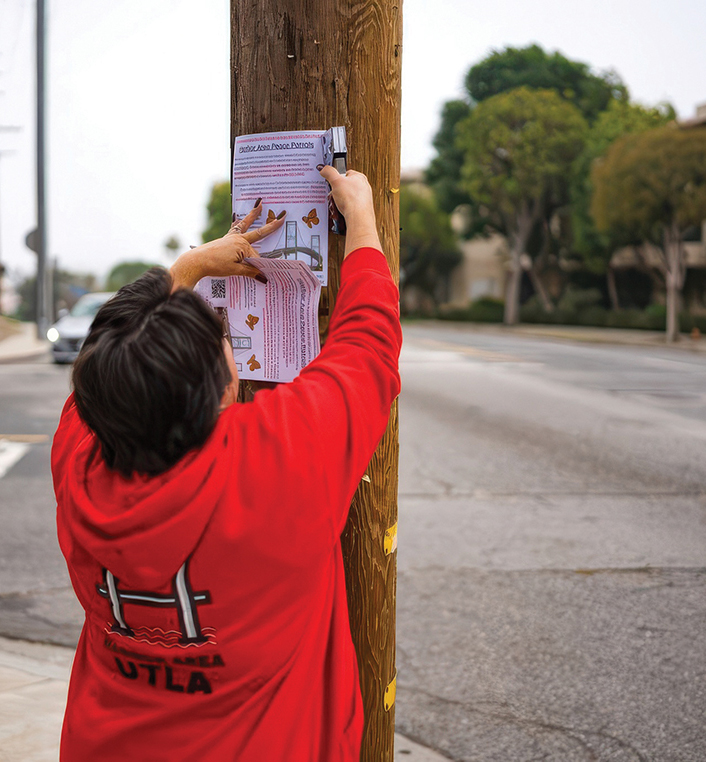

With the help of many of the same neighbors we’d called about the daycare, we began organizing community patrols in San Pedro and the neighboring community of Wilmington. Calling ourselves the Harbor Area Peace Patrol, we made daily circuits around our neighborhoods at dawn, distributing know-your-rights material and looking for signs of immigration enforcement at our local parks, grocery stores, and community centers.

We could not have begun this work without the support of fellow teachers. Through United Teachers Los Angeles (UTLA), the nation’s second-largest teacher union, we had connections to members of Unión del Barrio and the Community Self Defense Coalition — groups that had already instituted long-running community patrols throughout Southern California. We were able to draw on their experiences and contribute to their work and advocacy.

Many of our initial patrollers were fellow teachers, also setting aside time on their summer breaks to advocate on behalf of students and community members targeted — often indiscriminately — by federal immigration enforcers. Participating in these efforts, we saw that rank-and-file educators were central to resisting what we understand as a coordinated attack on our city. Working with these educators has been inspiring and illuminating — and it’s given us a new appreciation for the roles we can play as educators within our communities.

“As a teacher, my students are everything,” said Rigoberto Gandara, Unión del Barrio member and high school teacher in South Central LA. “I consider myself very qualified to teach the courses I teach, but what matters as much as any credential or subject expertise is the human element of teaching. For me, being a trusted resource for the community and fighting for the holistic development of our youth is the baseline for being a teacher.”

Gandara’s views were echoed by their colleague and fellow Unión del Barrio member Ron Gochez: “I think teachers make strong organizers because we are used to speaking with people on a daily basis and getting the best out of our students. Similarly, when we organize in the community, we try our best to get community members to participate in the work and to give it their best as well.”

The current wave of immigration raids in Los Angeles started in early June, just as the school year was wrapping up for nearly 1.3 million students across the county. At muted graduation ceremonies, families, students, and educators stood on guard as federal agents hunted down and abducted community members nearby. As an elementary school graduation took place in Huntington Park, Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents arrested day laborers down the block from the auditorium. Rumors quickly spread that ICE was targeting graduation ceremonies, forcing many families to make intense choices about whether or not to attend. Celebrations quickly turned into agonizing decisions about canceling to keep guests safe, and parks and restaurants were unusually quiet during this typically festive time of year.

High school teacher Rachel Bruhnke, who helped us to organize the Harbor Area Peace Patrol, told us the recent raids in Los Angeles activated a sense of community pride and responsibility. She felt strongly as someone who teaches in the same neighborhood she grew up in.

“When I first heard ICE was in San Pedro, I thought ‘Hell no,’” said Bruhnke. “Not in my town and not in my grandpa’s town. My grandfather, John Gault, contributed so much to strengthening this community. As an educator and organizer, his work in Latin America solidarity efforts helped lay the groundwork for much of today’s immigrant justice organizing in San Pedro and Los Angeles.”

With the surge in immigration raids came dramatic scenes of defiance shared on social media and quickly replayed on news stations around the globe: community members forcing federal officials out of their neighborhoods; farmworkers standing in the path of moving vehicles; driverless taxis set aflame and used as barricades.

These images of resistance — and the repression that followed — eventually faded as the media cycle moved on to other narratives. But the ICE raids and the community resistance continued as a new school year started in the fall.

Maya and Elijah leading a patrol meet up in San Pedro.

Maya putting up posters for the Harbor Area Peace Patrol.

In California, about one in five K–12 students come from mixed status families, meaning at least one parent is undocumented. Every school day, these students face the possibility of coming home to find a close family member missing. Just the other day I received a message from a student letting me know that since neighbors had observed someone taking photos of her father’s work truck, she and her siblings wouldn’t be coming to school. Messages like this are a sharp reminder of why this work matters.

According to UTLA leaders, enrollment across Los Angeles Unified has dropped by roughly 20,000 students this school year in conjunction with the increased ICE presence in our city. In addition to the trauma of losing so many students, this decline carries economic consequences for teachers and school support staff, who may find themselves displaced due to budget shortfalls.

UTLA has long taken progressive stances on issues that affect our students beyond the classroom — over-policing, environmental injustice, racial and economic inequity, and housing insecurity. By creating an Immigration Justice Team and hosting training sessions from groups like Unión del Barrio, the union filled the gaps left by the district by providing robust on-the-ground support for students and families.

“Working in Wilmington during the pandemic, I knew our students and families suffered,” said UTLA Area Chair Phylis Hoffman, who helped develop patrols at individual school sites before and after school.

“Students were cut off from each other, unable to build community and to do the things they loved, like go to school or the park, take swim lessons, play on their soccer and baseball teams, do cheer, band, and drill team.” Hoffman worried that the escalation of ICE raids would once again force students — particularly those who are or who have family members who are undocumented — to stay home as a way of avoiding ICE. “I enthusiastically supported the organizing because I knew we needed people to do the work of looking for ICE and reporting back to the community,” she said.

Gandara said colleagues have stepped up to meet the challenge.

“Members of the Educator Power slate hosted training sessions for UTLA members to prepare for the start of the academic year by creating school safety plans,” Gandara said:

These training sessions informed and guided the efforts with teachers at my school. We are now one month into the school year, and teachers at my school site are signing up for morning and after-school patrols every day of the week. Our students see us daily and know that they can come to us if they see anything alarming in the neighborhood. Staff at nearby schools also now recognize us since we patrol the elementary and middle schools in the area. And we often cross paths with teams of educators from other schools who are also vigilantly keeping an eye out to ensure that students and families make their way to and from school safely.

Beyond the community patrols, educators also initiated mutual aid efforts. Guadalupe Carrasco Cardona, ethnic studies teacher and chair of the LA chapter of the Association of Raza Educators (ARE) told us that ARE “decided that during the summer of 2025, we would raise funds and deliver groceries to families as a mutual aid campaign, coined ‘Revolutionary MutualCart.’” This was set up to aid both families who had members abducted by ICE, as well as families whose income earners were afraid to go to work due to the terror these abductions caused.

“The requests made from parents of our students kept us busy most of the summer,” Cardona reported. “In total we raised $16,000 and delivered groceries to approximately 150 families. Sadly, we continue to get requests from families.”

Educators continue to hold trainings across Los Angeles and with each new kidnapping, there are more staff, parents, and community members willing to get involved. Gandara comments,

What’s inspiring is the readiness with which teachers all across LA are answering the call to join this fight. For most of us, we already are among the first that families look to for resources and support. Whether or not most educators see themselves as community organizers, this is the moment where the lines between the two will blur more as we respond to the shameless, violent attempts to separate families. I know that for myself and my colleagues, we all feel compelled to show up.

With the new school year in full swing, showing up is no easy task. Patrols start before dawn, and the work it takes to keep a community advocacy group up and running takes many evening hours we might otherwise spend planning, grading, and recharging. But we’ve heard from enough community members, and received support from so many incredible people, that we know this work is worth it.

Recently, a new employee at our daughter’s daycare recognized one of us from a press conference we’d held at the Port of Los Angeles. “Are you . . . the teacher who fights ICE?” she asked shyly. “Thank you,” she said, “for everything you are doing.” It brought to mind an old expression: La maestra luchando también está enseñando — the teacher who is fighting is also teaching.