“No One is Going to Tell Us What is Right”

Language and Decolonization in Alaska

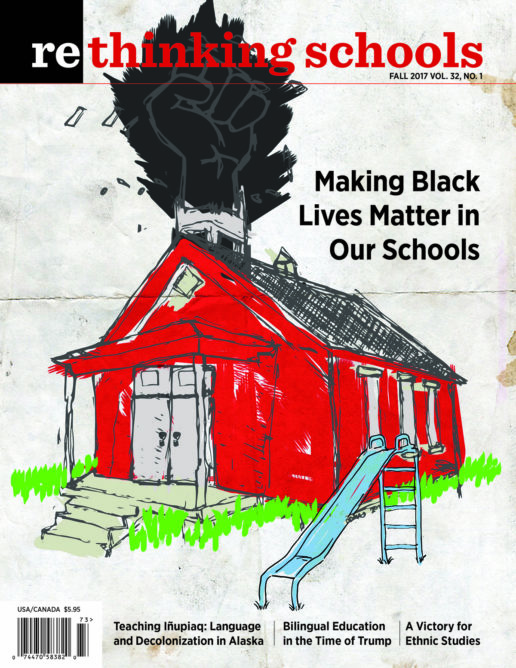

Illustrator: Nathaniel Wilder

Among the few things that those of us from beneath the Arctic Circle are likely to know about polar Alaska is that the Inuit peoples have dozens of words for snow. It’s such a darling and oft-repeated fact that one wonders if it’s legend. Yet inside a warm, 5th-grade classroom in Utqiaġvik, Alaska, on the edge of the Chukchi Sea — it’s 12 below zero outside and the wind is scouring the tundra — a group of 19 students sit at rapt attention, copying their new vocabulary words onto loose-leaf paper: the many Iupiaq words for snow.

“Qanataag,” the teacher writes on the board at the front of the class. The students repeat it back to her in a ragged chorus.

“Good,” she says. “Qanataag means ‘ice or snow overhang.'”

“Apua,” she writes next. It means “snow on the ground.”

The lesson continues. Nutagaq: freshly fallen, unpacked snow. Silliq: snow made crusty and hard by the wind.

This is one of three classrooms at Ipalook Elementary School that teach Iñupiaq, the language of the Iñupiat people who are native to this flat, frozen stretch of North America. In the North Slope Borough School District, of which Ipalook is a part, Iñupiaq is a required class for all students, kindergarten through 12th grade. Even non-Iñupiaq students — about a quarter of the North Slope population — must take a course in Iñupiaq, the language of the place where they are being raised. Thanks to the wounds of history and the pressures of modern life, Iñupiaq is fast disappearing, not unlike the sea ice that historically surrounds the North Slope for the majority of the year.

“Pukak,” the teacher writes. That’s the word for granular snow, she explains, which is best for melting into drinking water.

“Salumaniaq,” she adds beneath it.

One of her students knows this word already. “To clean the water!” she exclaims.

The vocabulary lesson is preparation for an upcoming five-week unit called Winter Sources of Drinking Water, or Immiugániq, in which the class will study the varied nature and scientific makeup of snow; how to turn it into safe drinking water, like their ancestors did and many of their family members still do; the impacts of dehydration; and the physical constitution of living things and their relationship to water. The unit is part of the Iñupiaq Learning Framework, an education-reform effort born in 2010 right here in Alaska’s North Slope, which is designed to couple contemporary, standards-based public schooling with the traditions, skills, and place-based knowledge native to this region. Like all units in the Iñupiaq Learning Framework, the drinking water curriculum is based not just on scientifically observed facts, but also on storytelling and students’ experiences in the world around them. It’s an education custom fit to the fact that, while all of these children live in homes with modern plumbing, nearly every one of them depends to some extent on subsistence fishing and hunting — on the caribou, ducks, Arctic foxes, walrus, and bowhead whales their families are able to find and kill. Many of the things they’ll be taught they already know, at least in part, but the curriculum is about connecting their practiced knowledge of the world to scientific understanding — and about connecting their community to the classroom.

“Sitchiyuiliaq,” the teacher writes. “Waterproof.”

“Like my coat!” a boy shouts. “Got one on right now,” he says. Despite the heat that’s on full blast, he’s zipped up in preparation for a fire drill. His classmates’ coats are on hooks by the door — Gore-Tex jackets from the AC Value Center hang next to traditional handmade fox furs and seal skins lined with bright-patterned fabric and decorative ribbon.

Waterproof: like these jackets, like the roof over the students’ heads, like walrus hide stitched into thigh-high boots for whaling crews. Like seal skin stretched over bone hulls forming the base of the crews’ canoes. Like Gore-Tex mittens. Like caribou stomach, which, when dried and turned inside out, can melt snow into water and hold it like a thermos.

In a couple of weeks, the students will be outside dressed in their waterproof coats, traditional and modern, drilling for core samples in the thinning ice. They’ll be collecting snow to observe and measure its properties and to learn its varied names and uses. The educators who developed the Iñupiaq Learning Framework feel confident that, by the end of the unit, students will better understand the world around them and be able to name and order that world in two languages. They’ll be a bit closer to holding a hybrid education: one that is situated in the context of contemporary life, but that incorporates long-held communal knowledge and old systems of oral, narrative instruction — the way all education used to be.

***

The North Slope of Alaska is a political assemblage of eight Iñupiaq villages scattered throughout 89,000 square miles above the Arctic Circle, stretching from the Brooks Range to the Chukchi Sea. None of the villages is accessible by road. Utqiaġvik hovers on the continent’s rim, against the ever-receding sheet of sea ice; with a population of 4,373, it’s the area’s largest town by far and the North Slope’s capital. A whaling hub past and present, it’s comprised largely of Iñupiaq people who have hunted and fished in this landscape for more than 10,000 years. (“Iñupiat” means “the real people.”) Though three-quarters of the North Slope’s 8,000 residents are native, only 988 of them — about 12 percent — are fluent speakers of Iñupiaq.

The language began to disappear because the state-run education system effectively banished it. In the late 1800s, Alaska’s general agent of education reported to the U.S. Congress that the “savages” in native Alaska needed to be educated “out of and away from the training of their home life. They need to be taught both the law of God and the law of the land.” During that period, and long after, the U.S. government, along with religious missionaries, opened repressive boarding schools for native children. These schools were far from students’ homes and the children were often taken against their families’ wills; parents were sometimes threatened with jail for refusing to send children away. The curriculum was Eurocentric: It focused on subjects that had little connection to students’ lives, and instruction was exclusively in English. Children who spoke their native languages were rapped on the knuckles, beaten, and forced to stand, facing the wall, holding stacks of encyclopedias until their arms quivered and burned. Versions of these institutions persisted through the 1970s.

“We were made to feel ashamed of who we are,” says Martha Stackhouse, an Iñupiaq elder who recounted her boarding school years.

So it’s no surprise, says Jana Pausauraq Harcharek, a longtime educator and the director of the Iñupiaq Learning Framework, that formal education became a suspect enterprise in the minds of many North Slope families — one from which students for generations would flee or within which they would fail. Yet attending school was, and is, the law of the land.

Harcharek is a commanding woman in her 50s with long, black hair and a studied stance on educational equity. She likes to emphasize the difference between “education” and “schooling.” In a 2015 article in the Journal of American Indian Education, she wrote that the advent of schooling in the North Slope was “a total strange concept”:

[It] meant that children no longer spent the days with parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, and extended family learning how to be human beings as they went along in life. In school buildings, they were told that speaking their language was bad; these negative images worked to deter them forever from the path of becoming full human beings.

Harcharek, herself Iñupiaq, explains that, along with the loss of the Iñupiaq language, her community has also lost access to long-held knowledge of their landscape, cultural history, and ancestry — in essence, knowledge of themselves.

Harcharek remembers noticing, even as a young child, how her native identity was denigrated and erased in the classroom. It happened in ways both big (the lessons about the “discovery” of Alaska by Europeans, for example) and small (she recalls being asked in elementary school to draw pictures of apple trees, a tree she had never seen before). Because of this, and in spite of it, Harcharek became an educator. Is there not some way, she wondered, to integrate schooling — the modern and government-mandated practice of children learning together, guided by a state-credentialed teacher — and education, the time-tested practice of learning from your surroundings and your family, as well as your community and its stories?

She knew that her vision would require a vastly different kind of education system: a classroom, a curriculum, and an overarching philosophy that could bridge the gap between modern schools and the generations-old knowledge of the Iñupiat people. It would also require thinking in what Harcharek calls “a decolonized context.” “We need to internalize the notion that no one is going to tell us what is right,” she says. “We know what is right.” With approval and encouragement from the school board, she and her team made a proposal, which started, as all good innovation does, with a question: What does a successful 18-year-old Iñupiaq student look like?

Beginning in 2006, Harcharek spent two years asking a version of that question to elders throughout the North Slope. She wanted to know: What should Iupiaq students understand, value, want, and dream? What do they need to get there? What should our schools look and feel like, and what should we teach in them? The elders’ response was almost unanimous: Given that the modern world is encroaching, and that the Earth itself is changing in ways both subtle and swift, it’s important to integrate the old ways and the new ways — traditional knowledge and contemporary thinking — into what the community’s young people are taught.

Today, the North Slope Bureau School District’s 12 Iñupiaq values — identified during those conversations with elders — hang in classrooms throughout the region:

Avoidance of Conflict

Humility

Spirituality

Cooperation

Compassion

Hunting Traditions

Knowledge of Language

Sharing

Family and Kinship

Humor

Respect for Elders and for Each Other

Respect for Nature

Harcharek and her team also developed four “realms” of the district’s core curriculum, all related to the Iñupiaq values: the Environmental Realm, which includes lessons about hunting, survival, and respect for the land; the Community Realm, which includes units on parenting, cooperation, and the roles of elders in the community; the Historical Realm, which includes storytelling and discussions of Iñupiaq culture in a global context; and the Individual Realm, which includes learning about leadership, values and beliefs, naming systems, and the cycle of life. Harcharek and others then painstakingly mapped the Iñupiaq Learning Framework to the state-mandated student-learning standards. (The Winter Sources of Drinking Water unit, for example, incorporates both the Alaska state standard for earth science and the Iupiaq Learning Framework’s standard for lessons about the complex technology developed by the Iñupiat people, which allows them to live in the harsh Arctic climate.)

Harcharek explains that the curriculum in the North Slope is about looking forward, but also about looking back — it’s about bridging the gulf between what was and what is. After a hunt, for instance, students dissect whale eyes to understand how the retina makes images with light, and they experiment with the animal’s fat to understand density. They build traditional sleds in geometry, dissect sharks in biology, and cook Iupiaq food in a course on nutrition science.

“The story of the Iñupiaq Learning Framework,” Harcharek and a colleague wrote in the Journal of American Indian Education, “is a story of the process by which our community engaged in claiming our existence, our vision, and our connection with places that change with the seasons.”

This spirit of reclamation is spreading beyond the classroom. In October, the residents of Barrow voted to change the name of their town back to its original name, Utqiaġvik.

***

Atqasuk, one of the North Slope’s smallest villages and home to roughly 300 residents — 95 percent of whom are Iñupiaq — has one school, the Meade River School, where 78 students enrolled in kindergarten through 12th grade go each day to learn. As the largest building in town, Meade River is also the de facto community center. This Friday, a funeral is scheduled to take place in the gym. Teachers will be responsible for locking and unlocking the school so mourners can grieve.

I’ve come here to see the Iñupiaq Learning Framework Winter Sources of Drinking Water unit in action. Perfect timing, Harcharek said: I could take the curriculum kit along with me, packed into two large boxes, and deliver it to Christine Cassidy, a teacher piloting the program in her combined 4th- and 5th-grade class. “We don’t want teachers to have to find anything,” Harcharek explained as she handed the kit to me back in Utqiaġvik. “Especially out in the villages.”

Cassidy, who is in her early 20s and originally from South Carolina, has less than two years of teaching experience in the North Slope. “I came to this district because of its focus on cultural integration,” she tells me. Cassidy has already seen the extent to which locally familiar anecdotes, examples, and stories impact students’ learning. Last year, a simple multiplication and division lesson had students imagine looking under a fence at the legs of horses; once she changed the image to caribou, or tutu, which she had students draw while swapping stories about their personal experiences with the animals, the lesson was instantly more engaging. The math, she says, “just clicked.”

The main Winter Sources of Drinking Water text is a storybook, a narrative about a mother, father, grandfather, and two children who load up a snow machine for a caribou hunt. Over the course of the multiday journey, the grandfather and parents teach the children to read the map and the landscape, how and where to collect snow, and about the perils of getting thirsty.

“Ataata explained that he used both silliq and pukak to melt into water,” the book reads, as the grandfather demonstrates the difference between the various layers of snow coating the ground. “Silliq yields the most water per volume because it is densest, but pukak is far easier to scoop into tea kettles or skin containers for melting.”

A difficult irony of the Iñupiaq Learning Framework is that the vast majority of people teaching the curriculum are, like Cassidy, outsiders. Much as the region’s communities want full control of their education system, very few people of Iñupiaq heritage become teachers: Though the North Slope Borough School District accounts for 18 percent of the region’s employment, the overwhelming majority of teachers here are non-native. They’re often from the lower 48, and they often plan to return home sooner or later — and usually sooner. Teacher shortages plague the North Slope, so much so that the district has an advertisement in Alaska Airlines’ inflight magazine: a photo of two smiling Iñupiaq children with a caption that reads “Teach in the North Slope Borough School District. Have the Adventure of a Lifetime.”

“Historically, teaching has not been seen in our communities as an honorable profession,” Harcharek explained. “My theory is that the more students begin to see themselves reflected in the content, in the school aesthetics, in the school lunches, the more they will want to become the teachers. They will begin to see it as honorable.” In the meantime, teachers like Cassidy are expected to learn everything they can about the Iñupiaq language, history, and culture. They receive trainings during annual “culture camps,” led by Iñupiaq elders and young people, in which they learn to hunt, break trail, make camp, carve baleen, identify native plants, and cook.

Cassidy opens the boxes I’ve brought as though cracking a treasure chest. Inside is a classroom set of the storybooks, as well as goggles, water bottles, maps of the route the storybook hunt takes through the inland Arctic Slope, a package of Ziploc bags, an inflatable globe, tracing paper, disposable gloves, a giant bottle of rubbing alcohol, a hot plate, Dixie cups, plastic spoons, and a few diapers that students will use to measure water density and absorption.

“I’d have to do an Amazon order two weeks in advance just to get these diapers,” Cassidy says, laughing.

During the upcoming unit, Cassidy will invite elders to share their experiences collecting water on the hunt, and to accompany the class into the field to collect snow. Back in the classroom, students will do a series of experiments, measuring their snow’s density, salinity, and melting rate. One will teach children the necessity of water for survival: they’ll dissolve the shells of eggs and drop one, still encased in its membrane, into a vat of water, while submerging another in rubbing alcohol. Each hour they’ll remove the eggs to weigh them. By the end of the day, the egg in alcohol will have shriveled almost unrecognizably.

“The purpose of the experiment is to understand the importance of hydration, but the challenges of alcoholism will also inevitably come up,” Cassidy predicts. The unit is simultaneously one of biological science, ecology and the human relationship to it, wilderness survival, history, and an opportunity to talk about contemporary challenges in the community.

“As Iñupiat, we are natural researchers,” says Emily Roseberry, the Meade River School principal and the only Iñupiaq principal in the North Slope. “We’re natural scientists.” Emily’s educational philosophy is not just about inspiring children to learn, but also about validating the knowledge they already have. As a science teacher, she encouraged students to look into things that truly interested them. She recalls one student who was at risk of failing because of his family’s several-week-long hunt, which would cause him to miss the class’s big research project. So she worked with him to plan a project he could conduct while hunting. They came up with a question, one that I was curious about myself: What do caribou eat in winter? He created a hypothesis, and, once he and his family killed the caribou, he opened the stomach and tested his idea. Sure enough, the animal was full of lichens that survive in permafrost.

The Iñupiaq Learning Framework makes hands-on projects like this possible, and normative, for all students — not just the ones who are lucky to have particularly dedicated teachers. “These are my people,” Roseberry says, “and I take their education very seriously. We need all of our students to have positive experiences here.”

***

The Iñupiaq Learning Framework raises a question that applies to schools everywhere: How can we build our curricula, and our educational philosophies, to inspire and reflect the communities they serve?

Of course, teaching to relevancy carries risks. If we teach children from agricultural communities only about farming, Indigenous Alaskans only about whaling and hunting, and urban youths only about the ways of the city, then the system will be inequitably confining. The Iñupiaq elders knew this. They wanted their schools to pair the so-called relevant with the universal — so that students can thrive at home but also be equipped if they choose to strike out into the great wide open.

It troubles Jana Harcharek, as it should us all, that we assume that children come to school as empty vessels whose brains need to be filled by state-certified teachers. “We wouldn’t be here,” she says, “if we hadn’t already figured a lot of things out.”

I tell Harcharek that, before coming to the North Slope, I’d thought of the Iñupiaq Learning Framework as a cultural preservation project. But now that I am here, I say, I’m starting to see her work as a kind of cultural resuscitation project. She agrees, though she takes polite issue with my word choice: “I never liked the word ‘preservation,'” she says. “It’s so limiting, as if you’re putting something in a box to look at and then just set aside.” And “resuscitation” seems to suggest something already dead, she adds. The Iñupiaq Learning Framework, she stresses, is about perpetuation.

***

The bell rings and the students in Megan Donnelly’s kindergarten class, in Utqiaġvik, open their notebooks and begin their morning work. Today they start a unit about careers, and Ms. Megan encourages them to write in their journals about what they might want to do when they grow up.

“I want to be a firefighter,” says a little boy. “I love fire trucks.” He informs me that a brand-new fire truck was recently airlifted into his town.

“From where?” I ask him.

“From far away!” he says.

A few minutes later, during circle time, the class takes turns naming all the jobs they can think of: pilot, scientist, cleaner. Someone who works at the AC Value Center. Teacher. And firefighter, of course.

“Hunter,” another student adds.

“That’s an important one,” Ms. Megan says, and writes it on the board at the front of the room.

The morning announcements come on over the loudspeaker. They include a pledge of allegiance, first in English, then in Iupiaq (admittedly an uncomfortable scene to behold, given the historical context). After, the announcer introduces the word of the week: miñuaqtuġvik, Iñupiaq for school.

“Miñuaqtuġvik,” the children repeat.

“Why is it important to learn Iñupiaq?” I ask the kindergartners, table by table, as they scribble away at their assignments.

“To talk to people,” one says.

“I have to teach my mom,” says another.

“I’m Iñupiaq!” squeals one girl named Alani as she pulls off her jacket. She’s come in late and is eager to get to her table and join the conversation. “Only my Aaka knows how to talk it, so I have to remember,” she says. She shows me the half-heart pendant her Aaka — her grandmother — had given her for Christmas. Her Aaka wears the other half.

A few weeks ago, Ms. Megan organized a round of show-and-tell. One of the students, Aag·luaq, age 6, brought in two frozen foxes she’d caught almost entirely on her own — her first catch. She had instructed her father where to set traps and went out with him on a snow machine a few days later to check them. Sure enough, she’d caught two kulhaak, or Arctic foxes. She brought them to class to show her friends who lined up at the back of the classroom to stroke the newly dead creatures’ thick fur. The young fox hunter, I learn, is Jana Harcharek’s granddaughter.

A longer version of this article was originally published in Orion Magazine.