Preview of Article:

My Talk With the Principal

Thoughts on putting up walls — and tearing them down

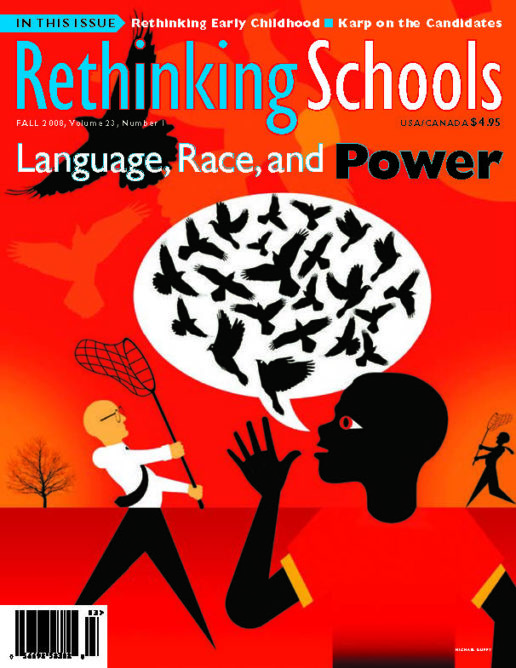

Illustrator: Roxanna Bikadoroff

I tried to gather myself before the meeting with my principal, but I could feel the knot in my stomach begin to tighten. “What have I done wrong now? What could she possibly want to talk about?” Her email said she had “some serious concerns… about what is and is not going on in your classroom.”

I knew I had to speak to her. Halfway to her office I started to think, “This must be what students go through when they’re asked to go to the office for reasons they don’t quite understand.”

My arrival in her office seemed to jostle her. She was consumed by a mass of paperwork on her desk. She raised her head, bleary-eyed, and invited me in. The tension in the room was palpable.

We exchanged a few awkward pleasantries. She clearly had an agenda for the meeting but seemed unsure how to begin. I broke the silence by asking what her serious concerns were about what was going on (or not going on) in my classroom.

She looked nervously down at her notes and began to talk to me about how there were things in our school that were negotiable and things that were non-negotiable. I knew exactly where she was going, but I let her continue. She explained that everyone in the school was supposed to have a word wall up in their classroom.

A word wall, I thought. Is that her problem?