My Grades Will Not Be Instruments of War

How we grade students — or whether we grade students — has always been contested terrain. The pandemic has brought new attention to the politics of grading.

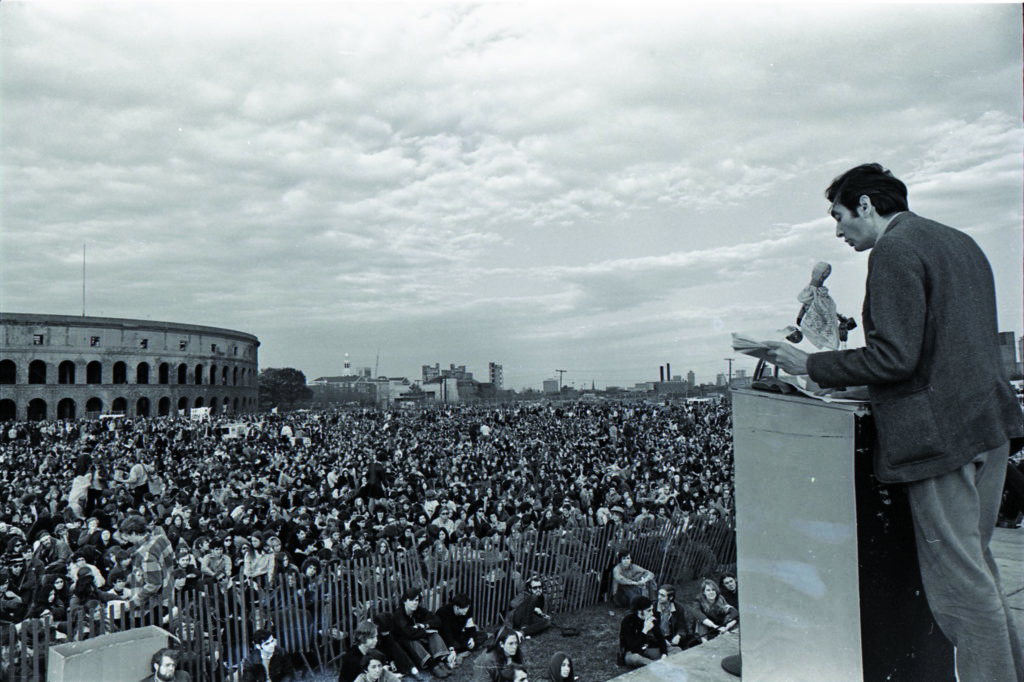

In the 1960s, the radical historian Howard Zinn was a professor at Boston University. The university’s administration agreed to report male students’ grades to the Selective Service System, which could help determine young men’s military draft status. Zinn announced that he refused to allow his grades to play a role in waging immoral wars. Zinn’s action is one eloquent moment in the history of educators who defied the grading policies of those allegedly in charge.

Zinn’s letter was recently uncovered by historian Robert Cohen, in the Howard Zinn Papers in the Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives at New York University, where Cohen is a professor. Cohen believes Zinn’s undated letter is probably from 1966.

Whatever a grade is or should be, I know that the grades that I, an instructor, give to my students cannot be instruments of our government in pursuit of war — aims that I disagree with on the most fundamental human, legal, moral, political, and even military grounds. I cannot allow my teaching to be so brutalized that it becomes merely another expression of our war efforts in policing the people of the world, people whose wishes and political desires are quite often in marked contrast to our own desires of stability, throughout our “free” world.

There is a quite good case that can be made for not deferring students from the draft in the first place: the effects of this are with great injustice to place the burden of our military conscription on the lower classes and the non-whites in our society. The middle class boy can usually escape the burdens of conscription merely by becoming a college student, a step that is normally a necessary part of his career anyway. By his role as a college student he becomes a vital resource of our society, one whose sacrifice to the ravages of war is not in the “national interest.” Such an arrangement is, to say the least, unjust, and there are good reasons for questioning a system that calls upon the lower classes and racial outcasts of society to bear the burden of its defense needs. Nonetheless, this is the existing system, and within the near future, there is little chance of changing it.

But the crisis is now. General [Lewis B.] Hershey, head of the Selective Service, has announced that within the near future we could expect students to become subject to the draft; not all students, however: merely those who are not able to rank sufficiently high in their class standing and on an examination. My course and its grades are then to become a part of the induction process; I am to confront my students with the fact that their failure to do well in various aspects of the course requirements will demonstrate that they are not vital to our national interests, and so, with their lower-class and non-white colleagues, must join the rest of our military in the Dominican Republic and Vietnam in policing the world.

I refuse to allow the grades I assign to students in my course be made their guarantee that they will not be part of our war effort. There is little realistic hope of my convincing the college where I teach that they should not give over to the government the class standings of their students: our colleges are far too married to the military needs of our society to take such a bold and responsible action. But I, an individual, can refuse to allow my grades to be so used and abused.

I can and do announce to my students that if they are opposed — for any reasons they feel to be legitimate, based on their moral or political opinions — to fighting in the present wars of our nation, I will treat their grades accordingly; that I will have two sets of grades for each of them that so informs me, one which I personally will refer to if I am asked to pass upon his future qualifications to go on for graduate education or to teach, and another one which will serve the official record — the official record which is now to become a part of our Defense Department.

Will there be misuses of this, will there be students who claim to be opposed for legitimate reasons when they are only trying to avoid burdens on their time or on their courage? Quite possibly there will be. But I am far more willing to see such a misuse of my conscience and trust than I am to see the other, far more odious misuse of the purpose of my education. I believe that the enlightenment of our colleges should remain totally divorced from the enforcement of our military aims.