#MeToo and The Color Purple

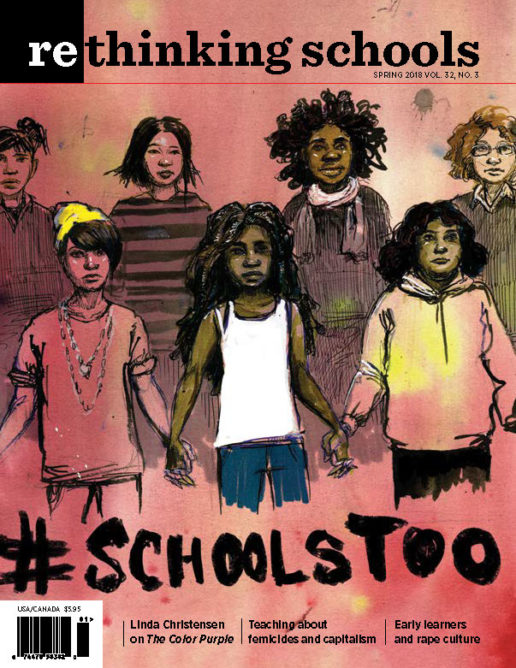

Illustrator: Hanna Barczyk

During a recent conversation, a former high school classmate said, “I always wondered why you left Eureka. I heard that something shameful happened, but I never knew what it was.”

Yes, something shameful happened. My former husband beat me in front of the Catholic Church in downtown Eureka. He tore hunks of hair from my scalp, broke my nose, and battered my body. It wasn’t the first time during the nine months of our marriage. When he fell into a drunken sleep, I found the keys he used to keep me locked inside and I fled, wearing a bikini and a bloodied white fisherman’s sweater. For those nine months I had lived in fear of his hands, of drives into the country where he might kill me and bury my body. I lived in fear that if I fled, he might harm my mother or my sister.

I carried that fear and shame around for years. Because even though I left the marriage and the abuse, people said things like “I’d never let some man beat me.” There was no way to tell them the whole story: How growing up and “getting a man” was the goal, how making a marriage work was my responsibility, how failure was a stigma I couldn’t bear.

The #MeToo movement has highlighted the breadth of sexual assault and violence against women in this country, and how we might challenge it in every aspect of our lives, including in our schools and our curriculum.

One powerful antidote is literature. Celie, Shug, Sofia, Nettie, and Mary Agnes from The Color Purple taught me that the shame I carried wasn’t mine, that the fear was real and necessary for survival, but they also taught me to question the roles and rules about womanhood that I learned at my mother’s knee. And they taught me about solidarity with other women, about finding my voice and using it.

As I write this article four decades after that foggy night, 120 students sit in a restorative justice circle in the hallways at Madison High School in Portland, Oregon (see page 8), talking about the sexual harassment they’ve experienced at school and demanding that the school create and enforce sexual harassment policies.

Hallelujah! What I experienced wasn’t unique — from catcalls to unwanted attention to my body to forced sex to physical and emotional abuse — but because schools refuse to acknowledge these issues, too many of us who experienced it covered our bruises and believed it was our fault.

At this #MeToo moment of history, this wake-up call for the women — and children and LGBTQ people — who have been physically, emotionally, and sexually abused and harassed, language arts teachers must be courageous enough to teach novels like The Color Purple.

I say courageous because The Color Purple has been banned across the country. The reasons vary: explicit sex, rape, “vulgar” language, and homosexuality. Novels with sexual abuse, violence, and gay characters are often deemed “inappropriate” for classroom use. What the #MeToo moment demonstrates is that the attempt to protect high school students from literature that exposes them to sexual abuse and sexual harassment has not protected them from experiencing it. Many students in our classrooms have already been abused, watched their fathers berate or beat their mothers, been ogled or touched without their consent, learned that girls need a boy to be OK, that boys can have sex and enjoy it, but girls who enjoy sex are sluts.

In order to teach students how to act differently, we must use our educational space to work for change. The issues most critical in our students’ lives are not taught in our curriculum: How to love yourself, how to select a partner who respects you, how to reject social boxes that perpetuate fixed gender roles, how to reject social and familial words and actions that promote harm, how to report sexual abuse.

As teachers we need to ask which systems in our schools and classrooms create conditions for these actions and perspectives to flourish and how can we fashion a different kind of classroom. When we look at our syllabus we need to ask, “Whose voices are heard and what stories are told? How are students nurtured to be their better selves?” If we want schools to prefigure the kind of society we want to live in, we need to change the syllabus.

In my work with a number of school districts in our area, I have asked members of high school language arts communities to make a list of each book they teach by grade level and then to note the gender and race of the main characters and authors. Every single district discovered that during their four years of high school language arts, students rarely encountered main characters or novels by women, writers of color, or LGBTQ authors. The novels most frequently taught: The Great Gatsby, The Catcher in the Rye, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Odyssey, The Scarlet Letter, and Lord of the Flies — all books with mostly male protagonists, written by men, deal with male issues, where women are objects of desire, absent, befuddled, or stoic.

To their credit, these school districts have spent the last decade updating their bookrooms with novels by authors of color and women. But as language arts teachers, we have to do more than weave women, queer folks, and authors of color into our classes. We have to consciously construct a curriculum that talks back to a society that allows sexual harassment to flourish like a virus in a hothouse. We need to fill the curriculum with issues most critical in our students’ lives. We need books that teach students about healthy relationships, finding their voices, and understanding their sexuality, and we need to teach them in a way that allows students to wrestle with these issues in literature and in their lives instead of building quizzes and tests about quotes and literary motifs. How else will young men learn to be empathetic partners in relationships? Where else will they learn that kindness and masculinity are not opposites? Where else will they understand how much harm their hands, bodies, and words can inflict?

We need to construct writing assignments that promote passageways into our students’ lives, and we need to provide safe spaces for students to share their stories — including ones like mine, filled with fear and shame — because those stories teach that we all are vulnerable and need caring communities to support us.

Our curricular choices demonstrate who we believe counts and what beliefs about society we promote. I want us to create curriculum that would have educated me enough to trust my first inklings of fear that said “This isn’t right,” instead of a curriculum that taught me that my job was to find, save, serve, or satisfy a man.

The Color Purple is the perfect vehicle for this re-education because the women in the novel suffer abuse and rejection, rise together in strength, and the men learn that instead of using their power to beat women, they can find courage to discover their humanity. Every character in the book teaches students how to overcome their past in order to become stronger human beings.

From Celie’s first letters to God, students learn that sexual abuse is about brutality, force, oppression; it is not about pleasure. Celie also teaches that women have the right to love and passion. When Celie and Shug find sexual pleasure with each other, they teach queer kids coming into their own sexuality that queer love is just as natural and beautiful as heterosexual love. And they teach straight kids that lesson too.

When Celie stands up to Mr._____, fueled by anger and her growing sense of her right to be in the world as a woman, Mr._____ is taken aback, as if a rug found a backbone and waved goodbye. Celie says, “I’m poor, I’m Black, I may even be ugly, but, dear God, I’m here, I’m here! . . . Time for me to get away from you, and enter into Creation.” Celie’s transformation telegraphs that when we assert our right to be in the world, to be seen and heard for who we are, we find our strength — strength enough to walk away from the fear and abuse and lies told about us.

Recently, one of my former students reached out, telling me that she has been in a relationship with a partner who physically and emotionally abused her. I helped her locate a program that finds housing and support for women and children experiencing abuse. If I hadn’t taught this book and told my story, would she have stayed?

When Sofia fights back against Harpo’s repeated attempts to rule over her, students learn how to refuse to bow to anyone’s fists:

All my life I had to fight. I had to fight my daddy. I had to fight my brothers. I had to fight my cousins and my uncles. A girl child ain’t safe in a family of men. But I never thought I’d have to fight in my own house. She let out her breath. I loves Harpo, she say. God knows I do. But I’ll kill him dead before I let him beat me.

In this scene, Sofia also teaches Celie — and us — about solidarity by confronting Celie for telling Harpo to beat Sofia into submission. When the two women finish their conversation, they take the pieces of Celie’s curtain that Sofia has cut up in her anger at Celie’s betrayal and they make a quilt. This is how we learn to confront injustice and use it as a tool to move forward.

The Color Purple also shows that people aren’t beyond redemption. Mr._____ learned abuse from his father and he handed it to his son Harpo. At one point in the novel he tells Harpo, “Well how you spect to make her mind? Wives is like children. You have to let ’em know who got the upper hand. Nothing can do that better than a good sound beating.” But Mr. _____, like Celie, is transformed. He comes to learn the error of his ways, to find pleasure in the conversation of women, and joy in sewing and cooking, traditionally women’s work.

Let’s teach The Color Purple and other content that helps our students critique oppressive patterns of gender and sex. Let’s open our classrooms to discuss all of the topics that book-banners want us to lock away and look away from. Let’s teach students to name harassment and rape, and to call out actions that belittle, shame, or hurt others. Let’s teach them to start a movement toward healing, through stories, through action, like the 120 students at Madison High School who sat in a hallway and called out for a different future.

Linda Christensen (lmc@lclark.edu) is director of the Oregon Writing Project at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon, and a Rethinking Schools editor. She is author, most recently, of Reading, Writing, and Rising Up: Teaching About Social Justice and the Power of the Written Word (2nd edition).

Hanna Barczyk’s work can be found at hannabarczyk.com.